Category:Green Business

- Now is the time to go beyond old ways of thinking, shaping new visions of our communities and our living planet

- #ActNow, Before It's Too Late

○

Speaking of green business, blue jeans epitomize Generation Green in multiple ways and fashion. Let's take a moment, in passing, to investigate as 'Blue Jeans Going Green'.

A free (unlocked/not behind a paywall) article from the Washington Post is illuminating...

○

Ten years ago, the Financial Times, a media voice of business, warned capitalism was 'in danger'

Today, in 2024, the warnings continue as the costs of 'business-as-usual' increase, as the productivity, international connectivity, trade and wealth increase...

“The next five to 10 years is the most critical time to accelerate the transition to a low-carbon economy. We think capitalism is in danger... We are going to be more aggressive because we have to.'” — “Capitalism is in Danger of Falling Apart”, Financial Times, July 27, 2014

○

Pension Funds Announce New Investment Strategies

September 8, 2015 / “David Blood and Al Gore Want to Reach the Next Generation” published by Institutional Investor

"The California State Teachers’ Retirement System [CalSTRS], the second-largest public pension fund in the U.S., with $191 billion in assets, was the first American institutional investor to invest in Generation.”

This was part of an oil/gas divestment campaign led by Ceres partner 350.org ... Jack Ehnes, CEO of CalSTRS, also serves on the board of Ceres.

In 2018, the Generation Investment fund reported progress in an April article published in the Financial Times -- Al Gore: Sustainability is History's Biggest Investment Opportunity.

“Generation lists large public sector investors among its clients, such as Calstrs, the $223bn Californian teachers’ pension plan, the $192bn New York State pension plan and the UK’s Environment Agency retirement fund. It also manages money for wealthy individuals but has stopped short of opening to retail investors. Almost all its assets are run in equity mandates, yet $1bn is invested in private equity.”

... (with) two investment funds – Global Equity and Asia Equity. The Global Equity fund is currently closed – there is a multi-year waiting list that is also currently closed. The minimum investment is $1 million and you need to be super-accredited. The fund seems to be targeted at institutional investors – not individuals. The Asia Equity fund is open but the same minimum requirements apply ($1M minimum).”

····················································································

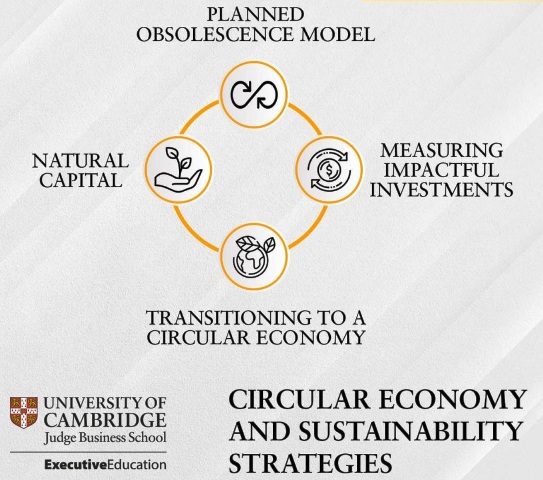

Designing & Building a Smart, Sustainable Future

- Clean & Renewable, Not Energy Inefficient, Not Wasteful, Moving Past Planned Obsolesence

Green Products @Home and @Work

- Day-by-Day, making a positive difference

○

May 2016

Book Review / Excerpt

Is Capitalism a Threat to Democracy?

The idea that authoritarianism attracts workers harmed by the free market, which emerged when the Nazis were in power, has been making a comeback

“Can Democracy Survive Global Capitalism?” (Norton) by Robert Kutner blames authoritarianism on politicians entranced by the free market

Like Karl Polanyi, Robert Kuttner believes that free markets can be crueller than citizens will tolerate, inflicting a distress that he thinks is making us newly vulnerable to the fascist solution"

Reviewed by Caleb Crain in The New Yorker

Keywords: Karl Polanyi; laissez-faire; John Maynard Keynes; Bretton Woods Conference; Thomas Piketty; "The Populist Temptation"; Milton Friedman and Alan Greenspan; Paul Volcker; "New Keynesianism"; "Washington Consensus"; "The China Shock"; "Why Liberalism Failed"

In Robert Kuttner’s telling, we were driven off the road after capitalists grabbed the steering wheel away from the Keynesians. The year 1973, in his opinion, marked “the end of the postwar social contract.” Politicians began snipping away restraints on investors and financiers, and the economy returned to spasming and sputtering. Between 1973 and 1992, per-capita income growth in the developed world fell to half of what it had been between 1950 and 1973. Income inequality rebounded. By 2010, the real median earnings of prime-age American workingmen were four per cent lower than they had been in 1970. American women’s earnings rose for a bit longer, as more women made their way into the workforce, but declined after 2000. And, as Polanyi would have predicted, faith in democracy slipped. Kuttner warns that support for right-wing extremists in Western Europe is even higher today than it was in the nineteen-thirties.

There is no shortage of villains in Kuttner’s narrative: financial deregulation; supply-side tax cuts; the decline of trade unions; the Democratic Party, which, by zigging left on identity politics and zagging right on economics, left conservative white working-class voters amenable to Donald Trump. Perhaps the most vexed issue Kuttner discusses, however, is trade policy—whether American workers should be protected against cheap foreign goods and labor.

The contours of the problem call to mind Polanyi’s account of enclosures in early-modern England. Half an hour with a supply-and-demand graph shows that free trade is better for every nation, developed or developing, no matter how much an individual businessperson might wish for a special tariff to protect her line of work. In a 2012 survey, eighty-five per cent of economists agreed that, in the long run, the boons of free trade “are much larger than any effects on employment.” But although free trade benefits a country over all, it almost always benefits some citizens more than—and even at the expense of—others. The proportion of low-skilled labor in America is

smaller than in most countries that trade with America; economic theory therefore predicts that international trade will, on aggregate, make low-skilled workers in the United States worse off. The U.S. government has, since 1962, compensated workers laid off because of free trade, but the benefit has never been adequate; only four people were certified to receive it during its first decade. In a 2016 paper, “The China Shock,” the economists David H. Autor, David Dorn, and Gordon H. Hanson wrote that, for every additional hundred dollars of Chinese goods imported to an area, a manufacturing worker is likely to lose fifty-five dollars of income, while gaining only six dollars in government help.

In a laissez-faire utopia, dislodged workers would relocate or take jobs in other industries, but workers hurt by rivalry with China are doing neither. Maybe they don’t have the resources to move; maybe the flood of Chinese-made goods is so extensive that there are no unaffected manufacturing sectors for them to switch into. The authors of “The China Shock” calculate that, between 1999 and 2011, trade with China destroyed between two million and 2.4 million American jobs; Kuttner quotes even higher estimates. NAFTA, meanwhile, lowered the wage growth of American high-school dropouts in affected industries by sixteen percentage points.

In “Why Liberalism Failed” (Yale), the political scientist Patrick J. Deneen denounces the assumption that “increased purchasing power of cheap goods will compensate for the absence of economic security.”

Kuttner follows Polanyi in attacking free-market claims of mathematic purity. “Literally no nation has industrialized by relying on free markets,” he writes. In 1791, Alexander Hamilton recommended that America encourage new branches of manufacturing by taxing imports and subsidizing domestic production. Even Britain, the world’s first great champion of free trade, started off protectionist.

Kuttner believes that America stopped supporting its manufacturing sector partly because it got into the habit, during the Cold War, of rewarding foreign allies with access to American consumers, and eventually decided that exports of financial services, rather than of manufactured goods, would be the country’s future. Toward the end of the century, as American manufacturers saw the writing on the wall, they shifted production abroad.

Kuttner doesn’t give a full hearing to the usual reply by defenders of laissez-faire, which is that a transition from goods to services is inevitable in a maturing economy—that the efficiency of American manufacturing means that it would likely be shedding workers no matter what the government did. Even Eichengreen, a critic of globalization, notes, in “The Populist Temptation,” that, if you graph the share of the German workforce employed in manufacturing from 1970 to 2012, you see a steady, grim decline very similar to that of its American counterpart, despite the fact that Germany has long spent heavily on apprenticeship and vocational training. The industrial revolution created widely shared wealth almost magically at its dawn: when an unemployed farmworker took a job in a factory, his power to make things multiplied, along with his earning power, without his having to learn much. But, as factories grew more efficient, fewer workers were needed to run them. One study has attributed eighty-seven per cent of lost manufacturing jobs to improved productivity.

When a worker leaves a factory, her power to create wealth stops being multiplied. The only way to increase it again is through education—by teaching her to become a sommelier, say, or an anesthesiologist. But efficiency gains are notoriously harder to come by in service industries than in manufacturing ones. There are only so many leashes a dog walker can hold at one time. As a result, if an economy deindustrializes without securing a stable manufacturing core, its productivity may erode. The dynamic has caused stagnation in Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa, and there are signs of a comparable weakening of America’s earning power.

Meanwhile, in the factories that remain, machines have grown more complex; the few workers they employ need to be better educated, further widening the gap between educated and uneducated workers. Kuttner dismisses this labor-skills explanation for job loss as an “alibi” with “an insulting subtext”: “If your economic life has gone to hell, it’s your fault.” This is intemperate but, in Kuttner’s defense, he has been warning American politicians to protect manufacturing jobs since 1991, and has been enlisting Polanyi in the cause for at least as long. Moreover, he has a point: to talk about productivity-induced job loss when challenged to explain trade-induced job loss is to change the subject.

In any case, if one’s concern is populism, it may not matter whether jobs have been lost to trade competition or to automation. In areas where more industrial robots have been introduced, one analysis shows, voters were more likely to choose Trump in 2016. According to another analysis, if competition with Chinese imports had been somehow halved, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania would likely have chosen Hillary Clinton that year. Economic explanations like these have been challenged. In April, the political scientist Diana C. Mutz published a paper finding that Trump voters were no more likely than Clinton ones to have suffered a personal financial setback; she concluded that Trump’s victory was more likely caused by white anxiety about loss of status and social dominance. But it’s not surprising that Trump voters weren’t basing their decisions on their personal circumstances, because voters almost never do. And Mutz’s own results showed that the factors most likely to lead to a Trump vote included pessimism about the economy and preferring Trump’s position on China to Clinton’s. It may not be possible to untangle economic anxiety and a more tribal mind-set.

Casting about for a Polanyi-style countermovement to temper the ruthlessness of laissez-faire, Kuttner doesn’t rule out tariffs. They’re economically inefficient, but so are unions, and, for a follower of Polanyi, efficiency isn’t the only consideration. A decision about a nation’s economic life, the Harvard economist Dani Rodrik writes, in “Straight Talk on Trade” (Princeton), “may entail trading off competing social objectives—such as stability versus innovation—or making distributional choices”; that is, deciding who gains at whose expense. Such a decision should therefore be made by elected politicians rather than by economists.

Basically there are two solutions,” Polanyi wrote in 1935. “The extension of the democratic principle from politics to economics, or the abolition of the democratic ‘political sphere’ altogether.” In other words, socialism or fascism. The choice may not be so stark, however. During America’s golden age of full employment, the economy came, in structural terms, as close as it ever has to socialism, but it remained capitalist at its core, despite the government’s restraining hand. The result was that workers shared directly in the country’s growing wealth, whereas today proposals for fostering greater financial equality hinge on taxing winners in order to fund programs that compensate losers. Such redistributive measures, Kuttner observes, are only “second bests.” They don’t do much for social cohesion: winners resent the loss of earnings; losers, the loss of dignity.

Can we return to an equality in workers’ primary incomes rather than to one brought about by secondary redistribution? In a recent essay for the journal Democracy, the Roosevelt Institute fellow Jennifer Harris recommends reimagining international trade as an engine for this rather than as an obstacle to it. When negotiating trade deals, for instance, governments could make going to bat for multinationals conditional on their agreeing to, say, pay their workers a higher fraction of what they pay executives.

Failing that, we’d be better off with redistributive programs that are universal—parental leave, national health care—rather than targeted. Benefits available to everyone help people without making them feel like charity cases. Kuttner reports great things from Scandinavia, where governments support workers directly—through wage subsidies, retraining sabbaticals, and temporary public jobs—rather than by constraining employers’ power to fire people. “We won’t protect jobs,” Sweden’s labor minister recently told the Times.

“But we will protect workers.”

○

GreenPolicy360: Advocating for Diversified Business with Green Values and Goals

Every Business, Every Supply Chain

Are you thinking and acting to make your supply chain green?

Be Climate Resilient

A company is only as good — and as protected — as its suppliers.

Forward-looking companies are engaging suppliers around health, safety, and environmental issues,

The Sustainability Initiative at MIT Sloan teaches changes that improve supply chain partners’ climate resilience...

○

Consider the Hannover Principles of Design

Review McDonough's "Design, Ecology, Ethics and the Making of Things", a "Centennial Sermon" delivered in the Cathedral of St. John the Divine , NYC, February 7, 1993

"Cradle-to-cradle" design ... developing green principles of sustainable practices "affirming life" on our home planet, envisiong green eco-nomics.

○

- Business and Investing for sustainable economics, social & progressive causes

- Business for Social Responsibility -- https://www.bsr.org/

- Social Venture Network -- http://svn.org/

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○

"New Economics", Concepts and Strategies

Communities and companies, non-profit and for-profit

Green Best Practices -- Smart Growth

Small-, medium- and large-businesses (SMBs)

Navigating through tides and all seas, winds and calm, storms and fair running

Changing, Competing, Charting a Successful Course

Venturing into a Sustainable Future

Acting with Short-term Objectives and Acting for the Common, Long-term Good

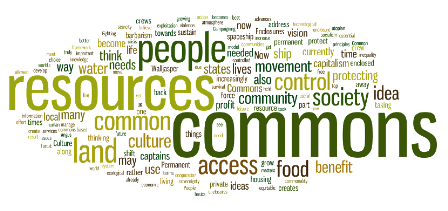

Envisioning "The Commons"

- Out-in-Front Politics

New Economics, People and the Planet

Sojourner: Reclaiming the Commons

○

Democracy Collaborative

Next System Project

○

Community-wealth generation focus:

- ○

Community business strategies:

~

Subcategories

This category has the following 21 subcategories, out of 21 total.

Pages in category "Green Business"

The following 65 pages are in this category, out of 65 total.

B

G

K

M

S

- Sacramento County, CA Sustainable Business Program

- Salt Lake City, UT e2 Business Program

- San Diego County, CA Green Business Program

- San Francisco, CA Green Business Program

- San Francisco, CA Municipal Code Pertaining to Green Business Program

- San Mateo County, CA Green Business Program

- Seed Saving

- Sharing Economy

- Stakeholder Theory

- Stuff

- Sustainable Development

W

Media in category "Green Business"

The following 146 files are in this category, out of 146 total.

- Acting to make a positive difference - in St Petersburg Florida.png 600 × 723; 645 KB

- Al-gore-future.jpg 586 × 390; 40 KB

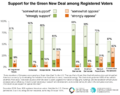

- American Jobs Act compared w THRIVE Act (Green New Deal).jpg 674 × 798; 90 KB

- AOC March 26, 2019.jpg 597 × 433; 58 KB

- ARPAE - energy innovation.jpg 693 × 461; 215 KB

- Aspen Trees Fall Colors Web-of-Roots Connected Wiki commons.jpg 800 × 533; 171 KB

- B Corporations certlogo.png 274 × 388; 14 KB

- Be kind-2.jpg 250 × 164; 20 KB

- Biggest climate related legislation in history - 1.png 800 × 188; 68 KB

- Bioneers 2023 - ThirdAct.Org.jpg 624 × 600; 145 KB

- Bioneers conf 2016.png 700 × 499; 1.03 MB

- Bioneers Conf 2021- Buckminster Fuller Instit joins.png 469 × 586; 599 KB

- Bioneers conference 2018-o.jpg 800 × 400; 134 KB

- Bioneers conference 2019 - 30 years anniv.jpg 800 × 400; 129 KB

- Bioneers It's all connected - 30th annual conference.jpg 527 × 521; 79 KB

- Bioneers-Hawken-Being Fierce and Fearless.jpg 751 × 685; 130 KB

- Bloomberg Carbon Clock 10-26-2021 8-47-05 AM EST.png 800 × 195; 356 KB

- Brazil INDC 2015.png 592 × 366; 301 KB

- Carbon Brief - Greenhouse gas levels 2021.png 640 × 436; 292 KB

- Carbon Footprint - BP-McKibben-Solnit-Aug2021.jpg 516 × 264; 66 KB

- Carbon-footprint small or large.jpg 149 × 258; 0 bytes

- Carbon-footprint.jpg 297 × 516; 59 KB

- Caroline Lucas-Green New Deal.jpg 584 × 391; 71 KB

- Catching the sun film.jpg 705 × 988; 366 KB

- Cause-related M Channel.jpg 700 × 531; 45 KB

- Challenge of Acting for the Commons.png 700 × 548; 175 KB

- Chile's electric bus fleet.jpg 543 × 541; 74 KB

- Circular Economy - Sustainable Strategies.png 543 × 480; 328 KB

- Climate action isn't 'bunny hugging' says Boris.jpg 800 × 264; 95 KB

- Climate Change and Insurance.png 247 × 82; 27 KB

- Climate Plan pledges as Oct6,2015.png 529 × 409; 101 KB

- Climate-Action-Plan-World Bank-2016.png 780 × 6,050; 3.2 MB

- Co-operative Enterprises ica.coop.png 704 × 339; 173 KB

- Common Ground, the Movie.png 600 × 756; 775 KB

- Commons-concepts permanent culture now s.png 448 × 211; 75 KB

- Commons-concepts permanent culture now.png 830 × 391; 39 KB

- Conversation prism.jpeg 561 × 600; 0 bytes

- Cradle to Cradle Products Innovation Instit.jpg 600 × 600; 72 KB

- Digital.png 427 × 116; 51 KB

- Drawdown - pushing climate action at work 2.png 640 × 955; 315 KB

- Drawdown - pushing climate action at work.png 632 × 777; 585 KB

- Drawdown Climate action, climate solutions.png 800 × 695; 246 KB

- Drawdown CO2 - Online Education solutions video.jpg 800 × 443; 124 KB

- Drawdown Solution Chart.png 800 × 450; 186 KB

- Drawdown.jpg 352 × 450; 53 KB

- Earth Day Flag.png 400 × 267; 69 KB

- Eco-labels.jpg 468 × 351; 68 KB

- ECOTRAM - Don Perry.png 800 × 474; 390 KB

- Electric busses-China.png 492 × 569; 277 KB

- Environmental Protection Agency logo.png 380 × 414; 39 KB

- EPA and the Green Bank - Feb 2023.png 476 × 542; 244 KB

- ERoadArlanda.png 800 × 495; 539 KB

- Escape from affluenza.gif 265 × 216; 15 KB

- EV charging stations news, US circa Feb 2022.jpg 629 × 480; 101 KB

- EV charging stations, US circa Feb 2022.jpg 519 × 480; 78 KB

- Fact Sheet-The American Jobs Plan.jpg 640 × 122; 16 KB

- Ford and Tesla make EV charging deal.jpg 336 × 419; 117 KB

- Gcf blgrnlogorgb.jpg 500 × 334; 50 KB

- Global fossil fuel emissions - in a lifetime graphic.png 600 × 657; 233 KB

- Global Green New Deal.jpg 427 × 640; 32 KB

- GND sign at capitol resolution announce.png 445 × 177; 96 KB

- Going Green 2019.jpg 800 × 356; 15 KB

- Gp360 logo.png 132 × 36; 4 KB

- Green Collar Economy.jpg 100 × 160; 6 KB

- Green High Five.png 406 × 146; 22 KB

- Green Marketing tag cloud 3.png 819 × 406; 128 KB

- Green New Deal - Bloomberg Jan 29,2019.png 640 × 757; 589 KB

- Green New Deal - Resolution.pdf ; 55 KB

- Green New Deal - Strategic Demands - Oct 1, 2021.png 602 × 658; 245 KB

- Green Wave.png 613 × 405; 427 KB

- Green-marketing 3.png 196 × 84; 10 KB

- Green-New-Deal-December-2018-1.png 800 × 634; 207 KB

- GreenBiz Drawdown story cover.png 888 × 712; 394 KB

- Greenhouse gas levels hit record - Reuters.jpg 600 × 696; 104 KB

- GreenLinks logo - 2.png 451 × 84; 13 KB

- GreenLinks logo.png 644 × 120; 10 KB

- GreenPolicy tag cloud m.png 450 × 223; 74 KB

- Image3.png 196 × 30; 2 KB

- It's a good day for a sunflower pic.png 520 × 553; 0 bytes

- Laudato Si On Care for Our Common Home.png 546 × 577; 108 KB

- Leonardo and Greta Nov 1, 2019.jpg 587 × 438; 60 KB

- Linked.jpg 316 × 475; 36 KB

- M Channel Envisioning the Future 4.png 700 × 845; 246 KB

- Manchin again - July 15 2022.png 600 × 654; 523 KB

- Map of the World wiki commons GTN800x370.png 800 × 370; 39 KB

- Mobile Development Impact GSMA as of 2015.png 823 × 839; 269 KB

- Mobile subscriptions outnumber world population 2015.jpg 599 × 427; 37 KB

- Naomi Klein speaking at the Bioneers conf.png 700 × 429; 385 KB

- Organic-chart-Jan-2016.pdf ; 136 KB

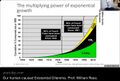

- Overshoot presentation - Rees 2.png 640 × 246; 81 KB

- Overshoot presentation by Prof William Rees - 2021.jpg 640 × 432; 76 KB

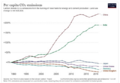

- Per capita CO2 emissions - to 2020.png 640 × 442; 153 KB

- Permaculture-observation tip.jpg 480 × 540; 86 KB

- Piece of a Protoplanet.jpg 632 × 600; 69 KB

- Planet Citizen green energy.JPG 720 × 480; 99 KB

- Planetcitizens-336x336.png 336 × 336; 206 KB

- Project Drawdown - Spring 2021.jpg 570 × 471; 85 KB

- Project Drawdown with Matt Scott - On Earth Day 2022.png 728 × 600; 224 KB

- Project Drawdown.jpg 400 × 437; 99 KB

- Rebuild the Dream.jpg 100 × 160; 6 KB

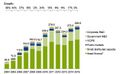

- Renewable Energy investment growth chart 2004-2014.jpg 600 × 368; 31 KB

- Renewable Potential US-Utility Scale PV.png 660 × 514; 57 KB

- Social Media icons free.png 650 × 270; 281 KB

- Social media icons.jpg 510 × 394; 64 KB

- Steven J Schmidt, May 2023.png 363 × 484; 383 KB

- Suburu Solterra - 2023.png 640 × 327; 541 KB

- Surprise climate deal.png 589 × 735; 83 KB

- Swap n Go Battery Time.jpg 460 × 302; 42 KB

- Tesla Freight Trucks - 2018.jpg 628 × 480; 50 KB

- There is no plan B because....png 575 × 308; 115 KB

- There is no Planet B (vimeo-2015).png 623 × 337; 80 KB

- ThereIsNoPlanetB.png 589 × 174; 181 KB

- Timelapse in Google Earth -1.jpg 800 × 241; 69 KB

- Timelapse in Google Earth-2.jpg 800 × 469; 151 KB

- Timelapse in Google Earth-3.jpg 372 × 556; 52 KB

- Timelapse in Google Earth-4.jpg 525 × 244; 51 KB

- Timelapse in Google Earth-5.jpg 800 × 528; 124 KB

- To be fully alive is to work for the common good.png 612 × 819; 621 KB

- To serve - from Chef José Andrés.png 600 × 798; 535 KB

- UN Climate Conf Dec2015.png 576 × 182; 42 KB

- UN DecinParis.png 296 × 277; 135 KB

- UNFCCC 21-logo.jpg 720 × 300; 17 KB

- Water Risk Projects.jpg 1,140 × 518; 124 KB

- Water Risk WWF2011.pdf ; 4.28 MB

- Water stress by country.png 2,159 × 1,115; 584 KB

- We Mean Business on Climate Change 2015.png 424 × 762; 136 KB

- Wetlands - Wetlands Day.png 640 × 492; 333 KB

- Who really invented the climate stripes - Climate Change Education.png 600 × 600; 234 KB

- Whole Earth Catalog-Internet Archive-4-23-2021.jpg 592 × 305; 48 KB

- Wiki IPCC m.jpg 602 × 339; 112 KB

- World Bank Group Climate Action Plan Apr2016.png 522 × 729; 244 KB

- World Bank Group Climate Change Action Plan 2016.png 512 × 256; 167 KB

- WorldBank GreenBondFactsheet.pdf ; 196 KB

- Youth vote estimates 2016 primary.png 800 × 490; 257 KB

- Topic

- Air Quality

- Alternative Agriculture

- Aquifers

- Atmosphere

- City-County Governments

- Civil Rights

- Clean Water

- Climate Policy

- Earth

- Earth Science

- Eco-nomics

- Ecology Studies

- Economic Development

- Economics

- Environmental Protection

- Environmental Security

- Food

- Green Best Practices

- Green Banking

- Green Infrastructure

- Green Politics

- Green Values

- Human Rights

- Initiatives

- Labor Issues

- Natural Resources

- Natural Rights

- Networking

- New Economy

- Oceans

- Renewable Energy

- Resilience

- Rights of Nature

- Sustainability

- Sustainability Policies

- Toxics and Pollution

- Workers Rights