Permafrost: Difference between revisions

Siterunner (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Siterunner (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 80: | Line 80: | ||

''Climate models show that current intergovernmental commitments to reduce warming – as laid out by the Paris Climate Accord – may not be enough, Romanovsky explains.'' | ''Climate models show that current intergovernmental commitments to reduce warming – as laid out by the Paris Climate Accord – may not be enough, Romanovsky explains.'' | ||

''In a 2016 report published in Nature Climate Change, researchers estimate that even if the climate was stabilised as agreed upon by the 196 parties in 2015, “the permafrost area would eventually be reduced by over 40%”.'' | |||

''However, with US President Donald Trump’s announcement of withdrawal from the Paris agreement last June, more permafrost loss is likely on the horizon.'' | |||

| Line 86: | Line 91: | ||

* [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FLCgybStZ4g ''Permafrost: The Tipping Time Bomb (Video)''] | * [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FLCgybStZ4g ''Permafrost: The Tipping Time Bomb (Video)''] | ||

'''''The | '''''The 'Blame Game' ''''' | ||

''Alaska is a politically conservative state, so outsiders might assume that residents reject the idea that the planet is warming beyond our control. The truth is more complex.'' | ''Alaska is a politically conservative state, so outsiders might assume that residents reject the idea that the planet is warming beyond our control. The truth is more complex.'' | ||

| Line 129: | Line 130: | ||

Correction: A quote by Bill Beaudoin has been corrected to state that it was Nicaragua that did not originally agree to sign the Paris climate agreement. | Correction: A quote by Bill Beaudoin has been corrected to state that it was Nicaragua that did not originally agree to sign the Paris climate agreement. | ||

<big>'''''[[Intended Nationally Determined Contributions]]'''''</big> | |||

Update: The announced US withdrawal from the Paris climate agreement has been accompanied by US policies to undercut climate research and regulations across a wide front. | Update: The announced US withdrawal from the Paris climate agreement has been accompanied by US policies to undercut climate research and regulations across a wide front. | ||

Read more about this retrenchment and retreat from environmental security concerns. | Read more about this retrenchment and retreat from environmental security concerns. | ||

| Line 139: | Line 143: | ||

<big>'''''[[Earth and Space, Politics]]'''''</big> | <big>'''''[[Earth and Space, Politics]]'''''</big> | ||

<big>'''''[[OCO-2]]'''''</big> | <big>'''''[[OCO-2]]'''''</big> | ||

Latest revision as of 17:24, 17 May 2018

The Great Thaw of America's North Is Coming

(Reprinted / BBC / Commons)

By Sara Goudarzi

16 October 2017

Vladimir Romanovsky walks through the dense black spruce forest with ease. Not once does he stop or slow down to balance himself on the cushy moss beneath his feet insulating the permafrost.

It’s a warm day in July, and the scientist is looking for a box that he and his team have installed on the ground. It’s hidden nearly six miles (10km) north of the Geophysical Institute at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks, where he’s a professor of geophysics and heads the Permafrost Laboratory.

The box, which is covered by tree branches, contains a data collector connected to a thermometer installed below ground for measuring permafrost temperature at different depths. Permafrost is any earth material that remains at or below 0C (32F) for at least two consecutive years.

Romanovsky connects his laptop to the data collector to transfer the temperature data for this location – called Goldstream III – which he will later add to an online database accessible to both scientists and interested individuals.

The thaw is deepening and expanding, causing the permafrost underneath to become less stable.

When the temperature of permafrost is below 0C (32F), for example -6C (21F), it is considered stable and will take a long time to thaw or to change. If it's close to 0C, however, it's considered vulnerable.

Every summer the portion of soil overlaying the permafrost, called the active layer, thaws, before refreezing the following winter. At Goldstream III, on this July day, the summer thaw currently ends at 50cm depth.

As the Earth warms and summer temperatures climb, the thaw is deepening and expanding, causing the permafrost underneath to become less stable.

The consequences, if this thawing continues, will be profound, for Alaska – and for the world. Nearly 90% of the state is covered in permafrost, which means entire villages will need to be relocated, as the foundations of buildings and roads crumble. And if this frozen cache releases the millennia of accumulated carbon it has locked within, it could accelerate the warming of our planet – far beyond our ability to control it.

A vulnerable state

As permafrost thaws, houses, roads, airports and other infrastructure built on the frozen ground can crack and even collapse.

“We are seeing some increased maintenance on existing roads over permafrost,” says Jeff Currey, materials engineer for Northern Region of the Alaska Department of Transportation Public Facilities. “One of our maintenance superintendents recently told me his folks are having to patch settling areas on the highways he's responsible for more frequently than they were 10 or 20 years ago.”

“In Point Lay – on the coast in northwest Alaska – for instance, they're having all sorts of trouble with their water and sewer lines buried in permafrost soil,” says William Schnabel, director of the Water & Environmental Research Center at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. “The permafrost soil has thawed and we get water and line breaks because the ground shifts.”

The concern is even more pronounced for those living in rural areas who don't have enough funds to combat the effects of thawing permafrost. For those residents it's not just about collapsing buildings, which is common now, but also water supply.

Often as permafrost thaws on the side of a lake that a village might use as water supply, there’s a breach and a lateral drain occurs. “It usually requires pretty expensive infrastructure to take water from a lake, bring it to a village and store it and all the components of this infrastructure are vulnerable to thawing permafrost,” Romanovsky says.

If a village depends on an affected lake for water, the community members would have to move their infrastructure and sometimes their entire village to another lake, which can be very costly.

According to research conducted by US Geological Survey, villages like Kivalina in north-west Alaska will have to move within the next 10 years, Romanovsky explains. “But estimates show cost of moving is about $200m (£150m) per village of 300 people.”

Those kinds of sums are only possible with federal government funding – but there are also no guarantees that a new location wouldn’t be affected eventually too.

“I think by now there are 70 villages who really have to move because of thawing permafrost,” Romanovsky says. “But moving villages to another location on permafrost is very difficult to guarantee for 30 years or so and the federal government doesn't want to pay for something they have to pay for again.”

It’s possible that building Alaskan settlements on permafrost may also be making the problem worse. “When you think about water and sewers you have to keep those above freezing and when you have permafrost you have to keep that below freezing,” Schnabel says. “So you're running relatively warm water through the permafrost and there's going to be some heat dissipation in there.”

Similarly, when a road is built, a lot of the vegetation that insulates the permafrost is cleared and then paved over with black covering that increases the amount of absorbed solar radiation. So although the maintenance burden has increased for those like Currey, not all the distress that comes with infrastructure can be solely attributed to a changing climate.

Defrosting a freezer full of carbon

Alaska, no doubt, is on the front lines of climate change, but the issues related to permafrost aren’t just specific to The Last Frontier. What happens to the frozen earth material in the 49th state will affect the lower 48, as well as the entire globe.

According to Romanovsky, half of the state’s and 90% of interior Alaska’s permafrost will thaw if there’s a global average rise of 2C in air temperature.

This is especially worrying because an enormous amount of organic carbon is sequestered in permafrost and the overlaying active layer. Since there’s not enough heat in frozen soil to help microbes to decompose dying vegetation, over thousands of years organic matter has accumulated in permafrost. Some estimates say the amount of carbon in the permafrost is more than two times than there is in atmospheric carbon dioxide.

“If we maintain our current course of operation, business as usual they call that, then it's pretty certain by 2100 a significant fraction of the permafrost in the upper five metres would thaw out and with it all the organic matter that is currently frozen in the permafrost,” says Kevin Schaefer, a research scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center at the University of Colorado. “That would indicate a release of carbon dioxide and methane, which would amplify the warming due to the burning of fossil fuels.”

If this carbon is released, the amount of CO2 will be three times more than what is in in the atmosphere now...

In fact, in a 2012 report published in the journal Nature, Schaefer and his co-authors indicated that past sudden warming events were essentially triggered by the release of carbon dioxide and methane from permafrost some 50 million years ago in Antarctica.

And the projected numbers don’t look promising: “Theoretically if this carbon is released to the atmosphere, the amount of CO2 will be three times more than what is in there [in the atmosphere] now,” says Romanovsky.

So it's a true feedback loop as it amplifies the warming due to the burning of fossil fuels. And despite the fact that the warming is accelerating, the feedback effects will be gradual, taking time to be noticeable. “It's a very slow feedback,” Schaefer says. “Imagine trying to steer a steam ship with a canoe paddle, that's the kind of feedback we're talking about.”

Unfortunately, once permafrost starts to thaw, it’ll be hard to refreeze it again – at least in our lifetime. Furthermore, once the decay is out of the ground and into the atmosphere, there’s no easy way to put that carbon back into the ground.

“The only way to do that would be to lower the global temperature and refreeze the permafrost, which would mean you're removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere,” Schaefer says.

Climate models show that current intergovernmental commitments to reduce warming – as laid out by the Paris Climate Accord – may not be enough, Romanovsky explains.

In a 2016 report published in Nature Climate Change, researchers estimate that even if the climate was stabilised as agreed upon by the 196 parties in 2015, “the permafrost area would eventually be reduced by over 40%”.

However, with US President Donald Trump’s announcement of withdrawal from the Paris agreement last June, more permafrost loss is likely on the horizon.

The 'Blame Game'

Alaska is a politically conservative state, so outsiders might assume that residents reject the idea that the planet is warming beyond our control. The truth is more complex.

According to a poll of 750 participants conducted earlier this year by the Alaska Dispatch News, more than 70% of Alaskans are concerned about the effects climate change.

“In Alaska anybody you ask will say ‘yes there's warming,’” Romanovsky says. “The farther north you go, northwest especially, the stronger that feeling. Because it's happening, you see it. Of course, the question of who's responsible depends on political beliefs.”

At Denali National Park & Preserve, park ranger Anna Moore has witnessed warming affect wildlife across only a couple of years. She’s noticed that the Arctic hare, which switches between brown and white coat colours with the seasons can’t seem to keep up with the changes as a result of temperature rise, essentially putting itself at risk.

“In the wintertime they get white tips to their hair,” Moore says. “As it gets warmer, the snow is melting faster, but their bodies are acclimatised to certain temperature change and so even though the snow is already melting they're still white and in more danger from predators.”

Moore says though she believes in climate change and is watching it affect flora and fauna at the park, she considers it a result of both human activities and a natural cycle.

Her colleague Ashley Tench also echoes the sentiment: “I agree with her [on] how it's part man-made and also natural.” To that effect, Tench doesn’t believe the United States’ pullout of the Paris Agreement makes a difference in the climate.

But not everyone in Alaska is on board with that sentiment. To Bill Beaudoin, a retired submariner and educator who’s now the proprietor of a bed and breakfast in Fairbanks, it’s obvious that humans are to blame and that we should work on reversing the effects of our actions.

People are worried, because of course there's no insurance for thawing permafrost...

“I think the Paris climate accord was necessary,” he says. “In fact, I didn't think [it was] enough. There's one country, Nicaragua, that didn't sign on to the agreement because they didn’t think it was strong enough. I would probably side with Nicaragua on that issue.”

No matter who is to blame for the warming and resulting thaw of permafrost, Alaskans are for the most part concerned about their future.

“People are worried, because of course there's no insurance for thawing permafrost,” Romanovsky says. “Insurance is not covering damage from permafrost like it does in California for earthquakes.”

Back at Goldstream III, Romanovsky notes that at 50cm depth, the temperature of the soil is -0.04C (31.9F). At one metre it’s -0.23C (31.5F). The last time he checked the data was in March, where at one metre, the soil temperature measured -1.1C (30F).

He takes his shovel and makes a hole in the ground to look at the soil and check for carbon within. Darker soil indicates accumulated organic carbon. The further down he digs, the colder the soil gets. Romanovsky digs until the shovel hits the permafrost and seemingly can’t go any further.

He pushes down a bit more and manages to dig up a bit of the permafrost – about the size of a small coin. Seconds after he holds the frozen soil between his fingers it melts as if it were an ice cube. He returns the dug up dirt back into the hole, disconnects his laptop from the data collector, closes up the box and covers it up with branches and packs up to leave the site. In a week he’ll head up north to log the temperature at other sites adding yet more data to one of the most comprehensive permafrost databases in the world.

Meanwhile, bit by bit, America’s frozen north is thawing and what happens next is unknown. What’s certain is the great thaw will forever change a once-familiar landscape – and likely a planet and its inhabitants too.

Correction: A quote by Bill Beaudoin has been corrected to state that it was Nicaragua that did not originally agree to sign the Paris climate agreement.

Intended Nationally Determined Contributions

Update: The announced US withdrawal from the Paris climate agreement has been accompanied by US policies to undercut climate research and regulations across a wide front.

Read more about this retrenchment and retreat from environmental security concerns.

Estimates of Permafrost Loss... Projected and Potential Consequences

2017

Why Alaska's Permafrost Isn't Permanent (Video Presentation)

Scientists in Alaska are drilling into the permafrost in an attempt to determine how much greenhouse gas could be released if rising temperatures cause the permafrost to thaw.

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○

2016

Warming May Mean Major Thaw for Alaskan Permafrost

Continued warming is melting down frozen ground, surprising scientists

https://nsidc.org/sites/nsidc.org/files/images/cryosphere/fig1.gif

Scientists estimate that five times as much carbon might be stored in frozen Arctic soils — permafrost — as has been emitted by all human activities since 1850. This worries people who study global warming. While emissions from permafrost currently account for less than 1 percent of global methane emissions, some researchers think this could change in dramatic ways as the world warms and that carbon-rich frozen soil breaks down.

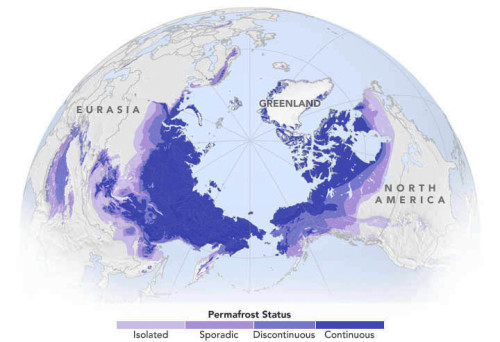

The map above, based on data provided by the National Snow and Ice Data Center, shows the extent of Arctic permafrost. Any rock or soil remaining at or below 0 degrees Celsius (32 degrees Fahrenheit) for two or more years is considered permafrost.

Continuous permafrost, which occurs in the coldest areas, refers to areas where frozen soil underlies more than 90 percent of the surface. Discontinuous permafrost occurs in slightly warmer areas, where frozen soils underlie 50 to 90 percent of the surface, while certain features such as rivers and south-facing slopes may be ice-free. In areas with sporadic permafrost, frozen soils underlie 10 to 50 percent of the surface. In areas with isolated permafrost, frozen soils underlie less than 10 percent of the surface, usually only occurring in depressions or north-facing slopes.

http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/IOTD/view.php?id=87794&eocn=home&eoci=iotd_title

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○

November, 2015

http://www.usgs.gov/newsroom/article.asp?ID=4400

Using statistically modeled maps drawn from satellite data and other sources, U.S. Geological Survey scientists have projected that the near-surface permafrost that presently underlies 38 percent of boreal and arctic Alaska would be reduced by 16 to 24 percent by the end of the 21st century under widely accepted climate scenarios. Permafrost declines are more likely in central Alaska than northern Alaska.

Northern latitude tundra and boreal forests are experiencing an accelerated warming trend that is greater than in other parts of the world. This warming trend degrades permafrost, defined as ground that stays below freezing for at least two consecutive years. Some of the adverse impacts of melting permafrost are changing pathways of ground and surface water, interruptions of regional transportation, and the release to the atmosphere of previously stored carbon.

“A warming climate is affecting the Arctic in the most complex ways,” said Virginia Burkett, USGS Associate Director for Climate and Land Use Change. “Understanding the current distribution of permafrost and estimating where it is likely to disappear are key factors in predicting the future responses of northern ecosystems to climate change.”

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○

● https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Permafrost

● https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tundra

A severe threat to tundra is global warming, which causes permafrost to melt. The melting of the permafrost in a given area on human time scales (decades or centuries) could radically change which species can survive there.

Another concern is that about one third of the world's soil-bound carbon is in taiga and tundra areas. When the permafrost melts, it releases carbon in the form of carbon dioxide and methane, both of which are greenhouse gases. The effect has been observed in Alaska. In the 1970s the tundra was a carbon sink, but today, it is a carbon source. Methane is produced when vegetation decays in lakes and wetlands.

The amount of greenhouse gases which will be released under projected scenarios for global warming have not been reliably quantified by scientific studies, although a few studies were reported to be underway in 2011. It is uncertain whether the impact of increased greenhouse gases from this source will be minimal or massive.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Methanogenesis -- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greenhouse_gas

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○

A self-reinforcing positive feedback loop is akin to a "vicious circle": It accelerates the impacts of anthropogenic climate disruption (ACD). An example would be methane releases in the Arctic. Massive amounts of methane are currently locked in the permafrost, which is now melting rapidly. As the permafrost melts, methane - a greenhouse gas 100 times more potent than carbon dioxide on a short timescale - is released into the atmosphere, warming it further, which in turn causes more permafrost to melt, and so on...

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○

Predicted rate of temperature change in Arctic

Arctic temperatures are expected to increase at roughly twice the global rate. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) will in their fifth report establish scenarios for the future, where the temperature in the Arctic will rise between 1.5 and 2.5°C by 2040 and with 2 to 7.5°C by 2100. Estimates vary on how many tons of greenhouse gases are emitted from thawed permafrost soils. One estimate suggests that 110-231 billion tons of CO2 equivalents (about half from carbon dioxide and the other half from methane) will be emitted by 2040, and 850-1400 billion tons by 2100. This corresponds to an average annual emission rate of 4-8 billion tons of CO2 equivalents in the period 2011-2040 and annually 10-16 billion tons of CO2 equivalents in the period 2011-2100 as a result of thawing permafrost. For comparison, the anthropogenic emission of all greenhouse gases in 2010 is approximately 48 billion tons of CO2 equivalents. Release of greenhouse gases from thawed permafrost to the atmosphere may increase global warming.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Permafrost#Carbon_cycle_in_permafrost

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○

Additional References re: Permafrost Science

Oct 2015 / Via Berkeley Lab -- A Simpler Way to Estimate the Feedback Between Permafrost Carbon and Climate

Simplified, data-constrained approach to estimate the permafrost carbon–climate feedback

Via University of Cambridge -- Analysis of the effects of melting permafrost in the Arctic points to $43 trillion in extra economic damage by the end of the next century, on top of the more than the $300 trillion economic damage already predicted

http://eusoils.jrc.ec.europa.eu/library/maps/Circumpolar/download/20.pdf

The intensity and extent of permafrost in the northern circumpolar region is commonly divided into four broad zones: continuous, discontinuous, sporadic and isolated...

Sleeping Giant Stirring in the Arctic -- https://www.nasa.gov/topics/earth/features/earth20130610.html#.VvwD7MdwI_4

Alaska's Stirring Permafrost -- http://landsat.gsfc.nasa.gov/pdf_archive/cape_halkett_4web.pdf

More re: Methane and Climate

Pay attention to Methane -- beyond the Arctic and Permafrost

Good Gas, Bad Gas: Burn natural gas and it warms your house. But let it leak, from fracked wells or the melting Arctic, and it warms the whole planet -- http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2012/12/methane/lavelle-text

(from GreenPolicy's former adviser, Bill McKibben) Global Warming’s Terrifying New Chemistry: Our leaders thought fracking would save our climate. They were wrong. Very wrong.

-- http://www.thenation.com/article/global-warming-terrifying-new-chemistry/

-- http://www.motherjones.com/environment/2014/09/methane-fracking-obama-climate-change-bill-mckibben

and ...

-- http://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/03/magazine/the-invisible-catastrophe.html

○

- Alaska

- Anthropocene

- Arctic

- Atmospheric Science

- Canada

- Climate Change

- Climate Migration

- Climate Policy

- Earth Observations

- Earth360

- Earth Science

- Earth Science from Space

- Ecology Studies

- Environmental Laws

- Environmental Protection

- Environmental Security

- Environmental Security, National Security

- Extinction

- Fossil Fuels

- Global Security

- Global Warming

- Green Politics

- INDC

- NASA

- NOAA

- Natural Resources

- New Definitions of National Security

- Ocean Science

- Planet Citizen

- Planet Citizens

- Planet Citizens, Planet Scientists

- Renewable Energy

- Resilience

- Sea-level Rise

- Sea-Level Rise & Mitigation

- Soil

- Solar Energy

- Strategic Demands

- Sustainability Policies

- US

- US Environmental Protection Agency

- Whole Earth