Missing Bugs

2019

Missing Bugs, Bugs Be Gone

The most common introductory example we use when we teach kids about interdependent ecosystems is insects. They may seem gross and small compared to the charismatic megafauna, we say, but insects play all sorts of important roles: pollinating plants, breaking down organic matter, feeding bigger animals. Without insects the whole web would collapse. I don't think many of us who have given this lesson actually contemplated the mass death of the world's insects as a possibility, imminent or otherwise. We should have.

A new study in the journal Biological Conservation takes a look at the global status of entomofauna (insects), and the picture is not good. The topline finding is that over 40 percent of insect species are threatened with extinction. That's a situation hard to describe without sounding like a heavy metal concert billing. (Megadeath, Ecocide, etc.) And the lesson about the ecosystem wasn't wrong: Without insects, Earth's environment as we've become familiar with it is toast. Even our apocalyptic thought experiments are coming true.

INDIGENOUS KNOWLEDGE HAS BEEN WARNING US ABOUT CLIMATE CHANGE FOR CENTURIES

"Indigenous peoples have witnessed continual ecosystem and species collapse since the early days of colonial occupation," says Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, an activist/scholar from the Nishnaabeg nation and author most recently of the book As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom Through Radical Resistance. "We should be thinking of climate change as part of a much longer series of ecological catastrophes caused by colonialism and accumulation-based society."

• Via the Guardian | Plummeting insect numbers 'threaten collapse of nature'

• Insect collapse | ‘We are destroying our life support systems’

• Via the NY Times | The Insect Apocalypse Is Here

The world’s insects are hurtling down the path to extinction, threatening a “catastrophic collapse of nature’s ecosystems”

More than 40% of insect species are declining and a third are endangered, according to the first global scientific review..

Insects... are “essential” for the proper functioning of all ecosystems, the researchers say, as food for other creatures, pollinators and recyclers of nutrients.

“Unless we change our ways of producing food, insects as a whole will go down the path of extinction in a few decades. The repercussions this will have for the planet’s ecosystems are catastrophic...."

○

The scientific review and analysis published in the journal Biological Conservation, says intensive agriculture is the main driver of the declines, particularly the heavy use of pesticides. Urbanisation and climate change are also significant factors.

The new analysis selected the 73 best studies done to date to assess the insect decline. Butterflies and moths are among the worst hit. Bees have also been seriously affected...

“The main cause of the decline is agricultural intensification. That means the elimination of all trees and shrubs that normally surround the fields, so there are plain, bare fields that are treated with synthetic fertilisers and pesticides.” The demise of insects appears to have started at the dawn of the 20th century, accelerated during the 1950s and 1960s and reached “alarming proportions” over the last two decades.

In the tropics, where industrial agriculture is often not yet present, the rising temperatures due to climate change are thought to be a significant factor in the decline.

“The evidence all points in the same direction,” said Prof Dave Goulson at the University of Sussex in the UK. “It should be of huge concern to all of us, for insects are at the heart of every food web, they pollinate the large majority of plant species, keep the soil healthy, recycle nutrients, control pests, and much more. Love them or loathe them, we humans cannot survive without insects.”

NY Times

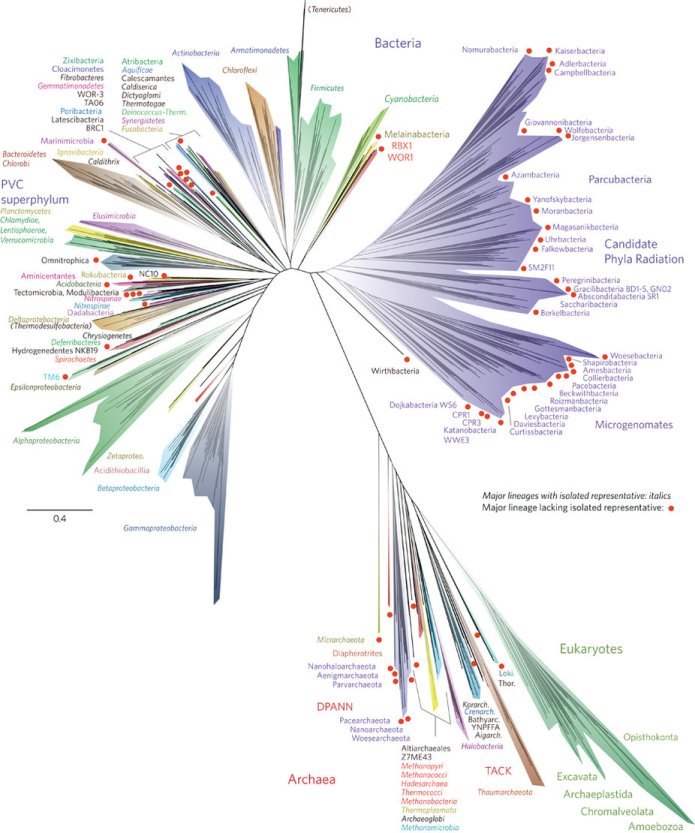

• https://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/12/science/scientists-unveil-new-tree-of-life.html

We’ve named and described a million species of insects, a stupefying array of thrips and firebrats and antlions and caddis flies and froghoppers and other enormous families of bugs that most of us can’t even name. (Technically, the word “bug” applies only to the order Hemiptera, also known as true bugs, species that have tubelike mouths for piercing and sucking — and there are as many as 80,000 named varieties of those.) The ones we think we do know well, we don’t: There are 12,000 types of ants, nearly 20,000 varieties of bees, almost 400,000 species of beetles, so many that the geneticist J.B.S. Haldane reportedly quipped that God must have an inordinate fondness for them.

A bit of healthy soil a foot square and two inches deep might easily be home to 200 unique species of mites, each, presumably, with a subtly different job to do. And yet entomologists estimate that all this amazing, absurd and understudied variety represents perhaps only 20 percent of the actual diversity of insects on our planet — that there are millions and millions of species that are entirely unknown to science.

"The Insect Apocalypse"

Insects are the vital pollinators and recyclers of ecosystems and the base of food webs everywhere. Riis was not alone in noticing their decline. In the United States, scientists recently found the population of monarch butterflies fell by 90 percent in the last 20 years, a loss of 900 million individuals; the rusty-patched bumblebee, which once lived in 28 states, dropped by 87 percent over the same period. With other, less-studied insect species, one butterfly researcher told me, “all we can do is wave our arms and say, ‘It’s not here anymore!’ ” Still, the most disquieting thing wasn’t the disappearance of certain species of insects; it was the deeper worry... that a whole insect world might be quietly going missing, a loss of abundance that could alter the planet in unknowable ways.

“We notice the losses,” says David Wagner, an entomologist at the University of Connecticut. “It’s the diminishment that we don’t see.”

Anyone who has returned to a childhood haunt to find that everything somehow got smaller knows that humans are not great at remembering the past accurately. This is especially true when it comes to changes to the natural world. It is impossible to maintain a fixed perspective, as Heraclitus observed 2,500 years ago: It is not the same river, but we are also not the same people.

A 1995 study, by Peter H. Kahn and Batya Friedman, of the way some children in Houston experienced pollution summed up our blindness this way: “With each generation, the amount of environmental degradation increases, but each generation takes that amount as the norm.” In decades of photos of fishermen holding up their catch in the Florida Keys, the marine biologist Loren McClenachan found a perfect illustration of this phenomenon, which is often called “shifting baseline syndrome.” The fish got smaller and smaller, to the point where the prize catches were dwarfed by fish that in years past were piled up and ignored. But the smiles on the fishermen’s faces stayed the same size. The world never feels fallen, because we grow accustomed to the fall.

Entomologists know that climate change and the overall degradation of global habitat are bad news for biodiversity in general, and that insects are dealing with the particular challenges posed by herbicides and pesticides, along with the effects of losing meadows, forests and even weedy patches to the relentless expansion of human spaces.

Amateurs have long provided much of the patchy knowledge we have about nature. Those bee and butterfly studies? Most depend on mass mobilizations of volunteers willing to walk transects and count insects, every two weeks or every year, year after year. The scary numbers about bird declines were gathered this way, too, though because birds can be hard to spot, volunteers often must learn to identify them by their sounds. Britain, which has a particularly strong tradition of amateur naturalism, has the best-studied bugs in the world. As technologically advanced as we are, the natural world is still a very big and complex place, and the best way to learn what’s going on is for a lot of people to spend a lot of time observing it. The Latin root of the word “amateur” is, after all, the word “lover.”

Some of these citizen-scientists are true beginners clutching field guides; others, driven by their own passion and following in a long tradition of “amateur” naturalism...

The current worldwide loss of biodiversity is popularly known as the sixth extinction: the sixth time in world history that a large number of species have disappeared in unusually rapid succession, caused this time not by asteroids or ice ages but by humans. When we think about losing biodiversity, we tend to think of the last northern white rhinos protected by armed guards, of polar bears on dwindling ice floes. Extinction is a visceral tragedy, universally understood: There is no coming back from it. The guilt of letting a unique species vanish is eternal.

But extinction is not the only tragedy through which we’re living. What about the species that still exist, but as a shadow of what they once were?

What we’re losing is not just the diversity part of biodiversity, but the bio part: life in sheer quantity.

Scientists have begun to speak of functional extinction (as opposed to the more familiar kind, numerical extinction). Functionally extinct animals and plants are still present but no longer prevalent enough to affect how an ecosystem works. Some phrase this as the extinction not of a species but of all its former interactions with its environment — an extinction of seed dispersal and predation and pollination and all the other ecological functions an animal once had, which can be devastating even if some individuals still persist. The more interactions are lost, the more disordered the ecosystem becomes.

Conservationists tend to focus on rare and endangered species, but it is common ones, because of their abundance, that power the living systems of our planet... “Humans seem innately better able to detect the complete loss of an environmental feature than its progressive change.”

In addition to extinction (the complete loss of a species) and extirpation (a localized extinction), scientists now speak of defaunation: the loss of individuals, the loss of abundance, the loss of a place’s absolute animalness.

We’ve begun to talk about living in the Anthropocene, a world shaped by humans. But E.O. Wilson, the naturalist and prophet of environmental degradation, has suggested another name: the Eremocine, the age of loneliness.

When asked to imagine what would happen if insects were to disappear completely, scientists find words like chaos, collapse, Armageddon. Wagner, the University of Connecticut entomologist, describes a flowerless world with silent forests, a world of dung and old leaves and rotting carcasses accumulating in cities and roadsides, a world of “collapse or decay and erosion and loss that would spread through ecosystems” — spiraling from predators to plants. E.O. Wilson has written of an insect-free world, a place where most plants and land animals become extinct; where fungi explodes, for a while, thriving on death and rot; and where “the human species survives, able to fall back on wind-pollinated grains and marine fishing” despite mass starvation and resource wars. “Clinging to survival in a devastated world, and trapped in an ecological dark age,” he adds, “the survivors would offer prayers for the return of weeds and bugs.”

~

- Agricultural Economics

- Agriculture

- Anthropocene

- Atmospheric Science

- Alternative Agriculture

- Aquifers

- Appropriate Technology

- Biodiversity

- Biogeosciences

- Bioneers

- Bioregionalism

- Climate Change

- Climate Policy

- Earth Science

- Eco-nomics

- Ecological Economics

- Ecology Studies

- Ecoregions

- EOS eco Operating System

- Extinction

- Farm-Related Policies

- Food

- Food-Related Policies

- Forests

- Global Security

- Green Best Practices

- Land Ethic

- Permaculture

- Pesticides

- Planet Citizens

- Planet Citizens, Planet Scientists

- Resilience

- Soil

- Sustainability

- Sustainability Policies