Category:Voting Rights: Difference between revisions

Siterunner (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Siterunner (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary | July 14, 2021 | ||

U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary | |||

Subcommittee on the Constitution | Subcommittee on the Constitution | ||

Hearing on “Restoring the Voting Rights Act After Brnovich and Shelby County” | Hearing on “Restoring the Voting Rights Act After Brnovich and Shelby County” | ||

| Line 31: | Line 33: | ||

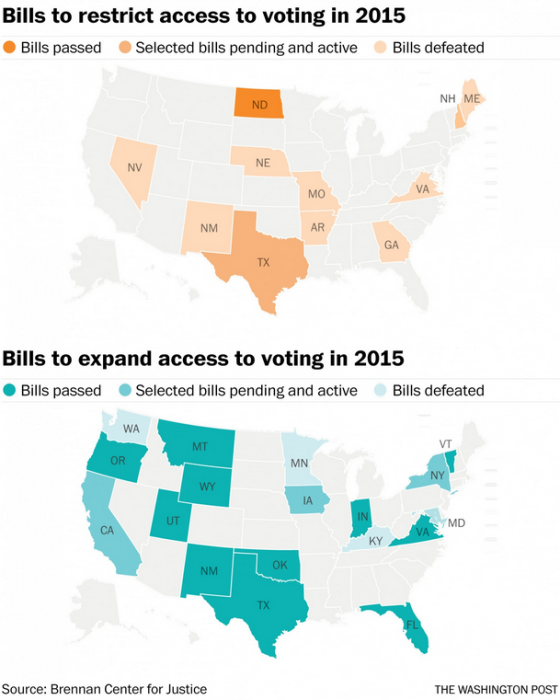

Once Section 5’s strictures came off, States and localities put in place new restrictive voting laws, with foreseeably adverse effects on minority voters. On the very day Shelby County issued, Texas announced that it would implement a strict voter-identification requirement that had failed to clear Section 5. Other States—Alabama, Virginia, Mississippi—fell like dominoes, adopting measures similarly vulnerable to preclearance review. The North Carolina Legislature, starting work the day after Shelby County, enacted a sweeping election bill eliminating same-day registration, forbidding out-of-precinct voting, and reducing early voting, including souls-to-the-polls Sundays. (That law went too far even without Section 5: A court struck it down because the State’s legislators had a racially discriminatory purpose.) States and localities redistricted—drawing new boundary lines or replacing neighborhood-based seats with at-large seats—in ways guaranteed to reduce minority representation. And jurisdictions closed polling places in mostly minority areas, enhancing an already pronounced problem. Pettigrew, The Racial Gap in Wait Times, 132 Pol. Sci. Q. 527, 527 (2017) (finding that lines in minority precincts are twice as long as in white ones, and that a minority voter is six times more likely to wait more than an hour). | Once Section 5’s strictures came off, States and localities put in place new restrictive voting laws, with foreseeably adverse effects on minority voters. On the very day Shelby County issued, Texas announced that it would implement a strict voter-identification requirement that had failed to clear Section 5. Other States—Alabama, Virginia, Mississippi—fell like dominoes, adopting measures similarly vulnerable to preclearance review. The North Carolina Legislature, starting work the day after Shelby County, enacted a sweeping election bill eliminating same-day registration, forbidding out-of-precinct voting, and reducing early voting, including souls-to-the-polls Sundays. (That law went too far even without Section 5: A court struck it down because the State’s legislators had a racially discriminatory purpose.) States and localities redistricted—drawing new boundary lines or replacing neighborhood-based seats with at-large seats—in ways guaranteed to reduce minority representation. And jurisdictions closed polling places in mostly minority areas, enhancing an already pronounced problem. Pettigrew, The Racial Gap in Wait Times, 132 Pol. Sci. Q. 527, 527 (2017) (finding that lines in minority precincts are twice as long as in white ones, and that a minority voter is six times more likely to wait more than an hour). | ||

The 1982 amendment to Section 2 created a broad statute in which Congress told courts to look at the “totality of the circumstances” in deciding whether a law gave minority voters “less opportunity” than white voters to participate and elect. | The 1982 amendment to Section 2 created a broad statute in which Congress told courts to look at the “totality of the circumstances” in deciding whether a law gave minority voters “less opportunity” than white voters to participate and elect. Among the factors were the socioeconomic conditions which could make minority voters face extra barriers to voting, and the tenuousness of the supposedly neutral justifications states could advance for passing restrictive voting rules. | ||

The Court in Gingles repeatedly referenced the Senate Report accompanying the 1982 Voting Rights Act amendments to understand the meaning of Section 2’s admonition that minority voters should not have “less opportunity” than other voters to participate in the political process and elect representatives of their choice: | The Court in Gingles repeatedly referenced the Senate Report accompanying the 1982 Voting Rights Act amendments to understand the meaning of Section 2’s admonition that minority voters should not have “less opportunity” than other voters to participate in the political process and elect representatives of their choice: | ||

The Senate Report which accompanied the 1982 amendments elaborates on the nature of § 2 violations and on the proof required to establish these violations. First and foremost, the Report dispositively rejects the position of the plurality in Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1980), which required proof that the contested electoral practice or mechanism was adopted or maintained with the intent to discriminate against minority voters. | The Senate Report which accompanied the 1982 amendments elaborates on the nature of § 2 violations and on the proof required to establish these violations. First and foremost, the Report dispositively rejects the position of the plurality in Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1980), which required proof that the contested electoral practice or mechanism was adopted or maintained with the intent to discriminate against minority voters. | ||

Although the Supreme Court interpreted Section 2 many times in the context of redistricting cases, until Brnovich, the Court had never interpreted the issue in vote denial cases, in which a state or locality makes it harder for minority voters to register and vote. Lower courts had read Section 2 to set forth a tough standard for overturning a state law, but one that could be met in appropriate cases. The 5th Circuit, for example, one of the country’s most conservative courts, held that Texas’ very strict voter identification law violated Section 2; | Although the Supreme Court interpreted Section 2 many times in the context of redistricting cases, until Brnovich, the Court had never interpreted the issue in vote denial cases, in which a state or locality makes it harder for minority voters to register and vote. Lower courts had read Section 2 to set forth a tough standard for overturning a state law, but one that could be met in appropriate cases. The 5th Circuit, for example, one of the country’s most conservative courts, held that Texas’ very strict voter identification law violated Section 2; when Texas eased its law in response to litigation, the 5th Circuit held it no longer violated the statute. Justice Alito’s opinion in Brnovich, ignoring the text of Section 2, the statute’s comparative focus on lessened opportunity for minority voters, and the history that showed | ||

Justice Alito’s opinion in Brnovich, ignoring the text of Section 2, the statute’s comparative focus on lessened opportunity for minority voters, and the history that showed | |||

involves charges of racism on the part of individual officials or entire communities,” it places an “inordinately difficult” burden of proof on plaintiffs, and it “asks the wrong question.” The “right” question, as the Report emphasizes repeatedly, is whether “as a result of the challenged practice or structure plaintiffs do not have an equal opportunity to participate in the political processes and to elect candidates of their choice.” | involves charges of racism on the part of individual officials or entire communities,” it places an “inordinately difficult” burden of proof on plaintiffs, and it “asks the wrong question.” The “right” question, as the Report emphasizes repeatedly, is whether “as a result of the challenged practice or structure plaintiffs do not have an equal opportunity to participate in the political processes and to elect candidates of their choice.” | ||

| Line 50: | Line 52: | ||

Nothing in Section 2’s text, history, or precedent supports a 1982 benchmark, a time when early voting was scarce and voter registration difficult in many places. This is the opposite of the nonretrogression principle that used to apply in Section 5 cases. That principle kept states from making voting worse; the Brnovich 1982 factor encourages rollbacks by setting 1982 as the baseline. | Nothing in Section 2’s text, history, or precedent supports a 1982 benchmark, a time when early voting was scarce and voter registration difficult in many places. This is the opposite of the nonretrogression principle that used to apply in Section 5 cases. That principle kept states from making voting worse; the Brnovich 1982 factor encourages rollbacks by setting 1982 as the baseline. | ||

The Brnovich guidepost naming the strength of the state’s interest in its voting rules turns the “totality of the circumstances” tenuousness standard on its head. Under the tenuousness standard, if a state passed a restrictive voting law and claimed it was necessary to stop voter fraud, the state would have to prove that this was the real justification and not a pretext for discrimination. As Justice Kagan explained in her dissent, “Throughout American history, election officials have asserted anti-fraud interests in using voter suppression laws.”20 | The Brnovich guidepost naming the strength of the state’s interest in its voting rules turns the “totality of the circumstances” tenuousness standard on its head. Under the tenuousness standard, if a state passed a restrictive voting law and claimed it was necessary to stop voter fraud, the state would have to prove that this was the real justification and not a pretext for discrimination. As Justice Kagan explained in her dissent, “Throughout American history, election officials have asserted anti-fraud interests in using voter suppression laws.”20 | ||

But the Brnovich guidepost in practice does exactly the opposite of searching for tenuousness: the Court repeatedly says restrictive state voting laws could be justified by a concern over voter fraud even if a state could not point to any fraud in its state to justify its challenged laws. | But the Brnovich guidepost in practice does exactly the opposite of searching for tenuousness: the Court repeatedly says restrictive state voting laws could be justified by a concern over voter fraud even if a state could not point to any fraud in its state to justify its challenged laws. | ||

| Line 56: | Line 59: | ||

suits by relying on racially discriminatory intent of a state legislature in passing restrictive voting rules. | suits by relying on racially discriminatory intent of a state legislature in passing restrictive voting rules. | ||

Congress should reverse this statutory decision through carefully-crafted legislation, just as Congress has done in the past, approving Voting Rights Act renewals and extensions by broad bipartisan majorities. | Congress should reverse this statutory decision through carefully-crafted legislation, just as Congress has done in the past, approving Voting Rights Act renewals and extensions by broad bipartisan majorities. Any new legislation will have to consider the scope of Congress’s power under Article I, Section 4’s “elections clause” to “make or alter” state rules regarding federal elections, as well as Congress’s power to pass voting legislation affecting federal, state, and local elections under its power to enforce the voting amendments, including the Fourteenth, Fifteenth, Nineteenth, Twenty-Fourth, and Twenty-Sixth Amendments. It also will have to consider that part of Brnovich in which the Court wrote that the dissent’s disparate impact test for finding Section 2 violations in vote denial cases might “deprive the States of their authority to establish non-discriminatory voting rules.” This statement appears like a threat to find new congressional voting rights legislation unconstitutional. | ||

Under our constitutional structure, Congress holds the lead rein in making the right to vote equally real for all U.S. citizens. These Amendments are in line with the special role assigned to Congress in protecting the integrity of the democratic process in federal elections. | Under our constitutional structure, Congress holds the lead rein in making the right to vote equally real for all U.S. citizens. These Amendments are in line with the special role assigned to Congress in protecting the integrity of the democratic process in federal elections. | ||

Revision as of 18:57, 17 July 2021

<addthis />

July 14, 2021

U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary

Subcommittee on the Constitution

Hearing on “Restoring the Voting Rights Act After Brnovich and Shelby County”

STATEMENT OF RICHARD L. HASEN

Chancellor's Professor of Law and Political Science* UC Irvine School of Law

Chair Blumenthal, Ranking Member Cruz, and Members of the Senate Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee on the Constitution:

Thank you for the opportunity to appear before you today to speak about the Supreme Court’s recent decision in Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee, a case which eviscerated Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act outside the context of redistricting. The opinion by Justice Samuel Alito is unmoored to the text of the statute, ignores the relevant history of Voting Rights Act, and thwarts Congress’s intent.

I begin with some history. A key component of the Act that Congress passed in 1965, Section 5, required states and localities with a history of racial discrimination in voting to ask either the U.S. Department of Justice or a three-judge court in Washington, D.C. for permission to change any voting rule. “Preclearance” required these jurisdictions to show that minority voters were not made worse off by the change; Congress intended to prevent states from passing new restrictive voting rules when courts struck down old ones. The idea behind preclearance was to prevent backsliding to worse conditions for voting, a concept that came to be known as “nonretrogression.”5

Section 5 helped a great deal until the Supreme Court in the 2013 case of Shelby County v. Holder held that the statute was no longer constitutional because it infringed on an invented state right to “equal sovereignty.” Although Section 5—when it was still in place—was effective in stopping new bad voting laws, it did not deal with discriminatory voting laws already on the books. Thus, if a state already had laws making it hard for minority voters to register or vote, Section 5 could not touch it.

In the years after passage of the initial Voting Rights Act, some litigants tried to use another part of the Act, Section 2, to attack restrictive voting rules already in place. At first the Court agreed that these challenges could go forward, but the Supreme Court in 1980’s City of Mobile v. Bolden case held that such challenges required proof of intentional discrimination.

Congress disagreed with the Supreme Court’s interpretation in City of Mobile, and in 1982 Congress passed a revised Section 2. The revision made clear that plaintiffs challenging voting rules did not have to prove that a jurisdiction acted with an intent to discriminate against minority voters; it was enough to show that “the political processes leading to nomination or election in the State or political subdivision are not equally open to participation” by members of a protected class “in that its members have less opportunity than other members of the electorate to participate in the political process and to elect representatives of their choice.” It is a type of disparate impact standard. As Justice Kagan’s dissent in Brnovich put it succinctly, “Section 2 demands proof of a statistically significant racial disparity in electoral opportunities (not outcomes) resulting from a law not needed to achieve a government’s legitimate goals.”

The effects of Shelby County were immediate and bad for minority voters, as Justice Kagan explained in her Brnovich dissent: Once Section 5’s strictures came off, States and localities put in place new restrictive voting laws, with foreseeably adverse effects on minority voters. On the very day Shelby County issued, Texas announced that it would implement a strict voter-identification requirement that had failed to clear Section 5. Other States—Alabama, Virginia, Mississippi—fell like dominoes, adopting measures similarly vulnerable to preclearance review. The North Carolina Legislature, starting work the day after Shelby County, enacted a sweeping election bill eliminating same-day registration, forbidding out-of-precinct voting, and reducing early voting, including souls-to-the-polls Sundays. (That law went too far even without Section 5: A court struck it down because the State’s legislators had a racially discriminatory purpose.) States and localities redistricted—drawing new boundary lines or replacing neighborhood-based seats with at-large seats—in ways guaranteed to reduce minority representation. And jurisdictions closed polling places in mostly minority areas, enhancing an already pronounced problem. Pettigrew, The Racial Gap in Wait Times, 132 Pol. Sci. Q. 527, 527 (2017) (finding that lines in minority precincts are twice as long as in white ones, and that a minority voter is six times more likely to wait more than an hour).

The 1982 amendment to Section 2 created a broad statute in which Congress told courts to look at the “totality of the circumstances” in deciding whether a law gave minority voters “less opportunity” than white voters to participate and elect. Among the factors were the socioeconomic conditions which could make minority voters face extra barriers to voting, and the tenuousness of the supposedly neutral justifications states could advance for passing restrictive voting rules.

The Court in Gingles repeatedly referenced the Senate Report accompanying the 1982 Voting Rights Act amendments to understand the meaning of Section 2’s admonition that minority voters should not have “less opportunity” than other voters to participate in the political process and elect representatives of their choice:

The Senate Report which accompanied the 1982 amendments elaborates on the nature of § 2 violations and on the proof required to establish these violations. First and foremost, the Report dispositively rejects the position of the plurality in Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1980), which required proof that the contested electoral practice or mechanism was adopted or maintained with the intent to discriminate against minority voters.

Although the Supreme Court interpreted Section 2 many times in the context of redistricting cases, until Brnovich, the Court had never interpreted the issue in vote denial cases, in which a state or locality makes it harder for minority voters to register and vote. Lower courts had read Section 2 to set forth a tough standard for overturning a state law, but one that could be met in appropriate cases. The 5th Circuit, for example, one of the country’s most conservative courts, held that Texas’ very strict voter identification law violated Section 2; when Texas eased its law in response to litigation, the 5th Circuit held it no longer violated the statute. Justice Alito’s opinion in Brnovich, ignoring the text of Section 2, the statute’s comparative focus on lessened opportunity for minority voters, and the history that showed

involves charges of racism on the part of individual officials or entire communities,” it places an “inordinately difficult” burden of proof on plaintiffs, and it “asks the wrong question.” The “right” question, as the Report emphasizes repeatedly, is whether “as a result of the challenged practice or structure plaintiffs do not have an equal opportunity to participate in the political processes and to elect candidates of their choice.”

In order to answer this question, a court must assess the impact of the contested structure or practice on minority electoral opportunities on the basis of objective factors. The Senate Report specifies factors which typically may be relevant to a § 2 claim: the history of voting-related discrimination in the State or political subdivision; the extent to which voting in the elections of the State or political subdivision is racially polarized; the extent to which the State or political subdivision has used voting practices or procedures that tend to enhance the opportunity for discrimination against the minority group, such as unusually large election districts, majority vote requirements, and prohibitions against bullet voting; the exclusion of members of the minority group from candidate slating processes; the extent to which minority group members bear the effects of past discrimination in areas such as education, employment, and health, which hinder their ability to participate effectively in the political process; the use of overt or subtle racial appeals in political campaigns; and the extent to which members of the minority group have been elected to public office in the jurisdiction. The Report notes also that evidence demonstrating that elected officials are unresponsive to the particularized needs of the members of the minority group and that the policy underlying the State’s or the political subdivision’s use of the contested practice or structure is tenuous may have probative value. The Report stresses, however, that this list of typical factors is neither comprehensive nor exclusive. While the enumerated factors will often be pertinent to certain types of § 2 violations, particularly to vote dilution claims, other factors may also be relevant and may be considered. Furthermore, the Senate Committee observed that “there is no requirement that any particular number of factors be proved, or that a majority of them point one way or the other.” Rather the Committee determined that “the question whether the political processes are ‘equally open’ depends upon a searching practical evaluation of the ‘past and present reality,’ and on a “functional” view of the political process.

Congress intended to alter the status quo and give new protections to minority voters, offered a new and very difficult test for plaintiffs to meet to show a Section 2 vote denial claim.

Rather than focus on the totality of the circumstances test written into the law and conduct a local, functional inquiry as explained in the key 1982 Senate Report—which itself drew from the Supreme Court’s decision in cases such as White v. Register—Brnovich offered non-binding so-called “guideposts” for decision.17 Eschewing the textualist approach purportedly favored by many of the Justices in the Brnovich majority, the opinion creates an ad hoc test meant less as guideposts and more like roadblocks for voting rights plaintiffs, giving states defending restrictive voting laws numerous ways of defeating Section 2 claims.

One guidepost rolls the clock back to 1982, holding that if a voting practice was not common during the year when Congress amended Section 2, it is likely not a violation for a state to eliminate the practice even if it would disparately impact minority voters. The idea that Section 2 requires plaintiffs to demonstrate that voting restrictions exceed the “usual burdens of voting”19 as they existed in 1982 is flatly contradicted by the textual command of Section 2 to find a violation when minority voters have “less opportunity” than others to participate in the political process and elect representatives of their choice.

Nothing in Section 2’s text, history, or precedent supports a 1982 benchmark, a time when early voting was scarce and voter registration difficult in many places. This is the opposite of the nonretrogression principle that used to apply in Section 5 cases. That principle kept states from making voting worse; the Brnovich 1982 factor encourages rollbacks by setting 1982 as the baseline.

The Brnovich guidepost naming the strength of the state’s interest in its voting rules turns the “totality of the circumstances” tenuousness standard on its head. Under the tenuousness standard, if a state passed a restrictive voting law and claimed it was necessary to stop voter fraud, the state would have to prove that this was the real justification and not a pretext for discrimination. As Justice Kagan explained in her dissent, “Throughout American history, election officials have asserted anti-fraud interests in using voter suppression laws.”20 But the Brnovich guidepost in practice does exactly the opposite of searching for tenuousness: the Court repeatedly says restrictive state voting laws could be justified by a concern over voter fraud even if a state could not point to any fraud in its state to justify its challenged laws.

Finally, even if a state passes a law with the intent to discriminate against minority voters, plaintiffs will have a hard time proving suits by relying on racially discriminatory intent of a state legislature in passing restrictive voting rules.

Congress should reverse this statutory decision through carefully-crafted legislation, just as Congress has done in the past, approving Voting Rights Act renewals and extensions by broad bipartisan majorities. Any new legislation will have to consider the scope of Congress’s power under Article I, Section 4’s “elections clause” to “make or alter” state rules regarding federal elections, as well as Congress’s power to pass voting legislation affecting federal, state, and local elections under its power to enforce the voting amendments, including the Fourteenth, Fifteenth, Nineteenth, Twenty-Fourth, and Twenty-Sixth Amendments. It also will have to consider that part of Brnovich in which the Court wrote that the dissent’s disparate impact test for finding Section 2 violations in vote denial cases might “deprive the States of their authority to establish non-discriminatory voting rules.” This statement appears like a threat to find new congressional voting rights legislation unconstitutional.

Under our constitutional structure, Congress holds the lead rein in making the right to vote equally real for all U.S. citizens. These Amendments are in line with the special role assigned to Congress in protecting the integrity of the democratic process in federal elections.

If Congress considers rules to restore either Section 2 or Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, it will have to offer record evidence showing constitutional voting rights violations within the states, and the need for congruent and proportional legislation to deal with the scope of the constitutional violations.28

Thank you for the opportunity to present these views. I welcome your questions.

○

Voting Suppression, Democracy Challenged

Opinion by Michelle Au

March 27, 2021

Michelle Au, a Democrat, is a Georgia state senator.

What struck me the most was the noise coming from all the wrong places.

Thursday afternoon, I sat in the chamber of the Georgia State Senate and watched as my colleagues, one after another, went up to the well to speak out against Senate Bill 202, a true Frankenstein’s monster of voter-suppression measures. It was clearly designed to ensure that a record Democratic turnout like the one in November — and in the state’s U.S. Senate runoffs in January — never happens again.

This hastily sewn-together bill is a broad attack on voting rights. It includes imposing limits on the use of mobile polling places and drop boxes; raising voter identification requirements for casting absentee ballots; barring state officials from mailing unsolicited absentee ballots to voters; and preventing voter mobilization groups from sending absentee ballot applications to voters or returning their completed applications. The list goes on.

In perhaps the most petty, direct attack on voters of color — who disproportionately are forced to stand in long lines to vote in Georgia — the measure, supposedly to prevent undue influence, outlaws providing food or drinks to voters waiting to exercise their democratic rights.

The bill had sailed through a House vote earlier that day, landing on our desks for approval about 3 in the afternoon. My fellow Senate Democrats and I knew, as the minority party in more ways than one, that we didn’t have the votes to kill the legislation. But one by one, we tried our hardest. Speakers pointed out the bill’s dubious legality, its de facto permission for the state to wrest control of county elections, its crippling cost burden, its blatant disenfranchisement of minority, immigrant, working-class voters.

This discussion lasted hours, a passionate chorus taking a last stand to defend foundational democratic principles. But what struck me the most was the Republicans’ silence.

From the back of the room, at my desk, I could see a sea of empty Republican seats — for senators who couldn’t even bother to sit in the room and pay even the tiniest respect to a discussion fundamental to the rights and interests of those they purport to represent.

While my Democratic colleagues raised their voices in defense of these rights, the silence of the Republicans in the chamber was deafening.

But it wasn’t quiet everywhere. In the Senate anteroom, a small, clubby space off to the side of the chamber, filled with tufted leather furniture, I could hear plenty of noise from behind the heavy wood doors. Laughter, hearty conversation, an occasional jovially raised voice. This was where the Republicans’ noise was, this was where their attention lived — in a small, exclusive room, its walls lined with decades of photos of past legislators who looked so much like them.

As expected, the bill passed along party lines. Gov. Brian Kemp, also a Republican, signed it into law about an hour later. The Georgia General Assembly is not an institution known for its blistering efficiency, and I have never seen anything at the Capitol happen quite as quickly as this.

Signings on important bills are often done publicly, with some fanfare, alongside key legislators and in front of the public and the news media. This piece of legislation was signed behind closed doors.

But even at that moment, there was more righteous noise. A Democratic House representative, Park Cannon, was arrested after she knocked on the governor’s office door, asking to be allowed to watch a bill-signing ceremony affecting the lives of so many Georgians.

From the third floor, I could hear the shouts, the footfalls, and watched as she was roughly escorted out of the building. Cameras swarmed, and colleagues and bystanders screamed, demanding to know why she was being arrested.

Cannon was charged with two felony offenses, The Post reported, “for obstructing law enforcement and preventing or disrupting General Assembly sessions or other meetings of members.” She has vowed to contest the charges.

Near the end of the evening, before the Senate vote, one of my Republican colleagues had taken to the well to close the discussion. Unbelievably, Sen. John Albers called SB 202 a measure to enhance voting access, and painted my colleagues’ framing of the bill as a distortion. “The truth matters,” Albers repeated earnestly. It is unclear how much the Republicans actually believe this narrative, but one thing is resoundingly clear: their indifference to the basic principles of democracy.

Read more at the Washington Post:

Greg Sargent: A scorching reply to Georgia’s vile new voting law unmasks a big GOP lie

Ruth Marcus: Georgia’s repulsive new election law is Exhibit A in the GOP’s war on voting rights

Jennifer Rubin: States that pass Jim Crow-style voting laws will feel the backlash

Paul Waldman: [https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2021/03/11/republicans-have-stopped-pretending-they-arent-trying-suppress-democratic-votes/ Republicans have stopped pretending they aren’t trying to suppress Democratic votes\

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

Fox News Channel

Trump praises, Biden decries Georgia's new election bill

The bill swiftly made its way through the Georgia legislature and was signed by Gov. Brian Kem

Joe Manchin Calls for Bipartisan Solution to Pass Sweeping Voting Rights Bill

○

Voting Rights, Democracy in Action

Historic moment in the U.S. -- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Voting_Rights_Act_of_1965

○

Voting Rights in US / Issues

Health of State Democracies / Center for American Progress Action Fund

○

ALEC and Voter Access

http://www.thenation.com/article/alec-exposed-rigging-elections/

Re: ALEC/American Legislative Exchange Council

Republicans have argued for years that “voter fraud” (rather than unpopular policies) costs the party election victories. A key member of the Corporate Executive Committee for ALEC’s Public Safety and Elections Task Force is Sean Parnell, president of the Center for Competitive Politics, which began highlighting voter ID efforts in 2006, shortly after Karl Rove encouraged conservatives to take up voter fraud as an issue.... ALEC’s magazine, Inside ALEC, featured a cover story titled “Preventing Election Fraud” following Obama’s election. Shortly afterward, in the summer of 2009, the Public Safety and Elections Task Force adopted voter ID model legislation. And when midterm elections put Republicans in charge of both chambers of the legislature in twenty-six states (up from fifteen), GOP legislators began moving bills resembling ALEC’s model....

○

Voting Rights Organizations (US)

Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund - http://www.aaldef.org/

ACE Electoral Knowledge Network - http://aceproject.org/

Alliance for Democracy - http://alliancefordemocracy.weebly.com/

American Promise - http://alliancefordemocracy.weebly.com/

Audit Elections USA - http://www.auditelectionsusa.org/

Ballot Access News - http://ballot-access.org/

Ballotpedia - https://ballotpedia.org/

Brennan Center for Justice - https://www.brennancenter.org/criminal-disenfranchisement-laws-across-united-states

Citizens for Election Integrity Minnesota - http://ceimn.org/about-us

Coalition for Free and Open Elections - http://www.cofoe.org/

Color of Change - https://www.colorofchange.org/

Common Cause - https://www.commoncause.org/

Democracy Matters - http://www.democracymatters.org/

Every Voice - https://everyvoice.org/

Fair Elections Legal Network - http://fairelectionsnetwork.com/ / http://fairelectionsnetwork.com/state-guides/

FairVote - http://www.fairvote.org/

Lawyer’s Committee for Civil Rights - https://lawyerscommittee.org/

League of Women Voters - https://www.lwv.org/

Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund - http://www.maldef.org/

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People - http://www.naacp.org/

No More Stolen Elections - https://www.nomorestolenelections.org/

Open Debates - https://www.opendebates.org/

Public Citizen - https://www.citizen.org/

Rock the Vote / https://www.rockthevote.org/

Save Our Elections - http://www.saveourelections.org/home

Sentencing Project - http://www.sentencingproject.org/issues/felony-disenfranchisement/

Southern Coalition for Social Justice - https://www.southerncoalition.org/program-areas/voting-rights/

Southern Poverty Law Center - https://www.splcenter.org/

Verified Voting - https://www.verifiedvoting.org/

Voice of the Experienced - https://www.vote-nola.org/

Voto Latino - http://votolatino.org/about-us/

Wolf PAC - http://www.wolf-pac.com/

○

Subcategories

This category has the following 19 subcategories, out of 19 total.

B

C

D

E

I

M

R

V

W

Pages in category "Voting Rights"

The following 26 pages are in this category, out of 26 total.

G

- Green Best Practices

- Green Politics with GreenPolicy360

- Green Stories of the Day

- Green Stories of the Day - GreenPolicy360 Archive

- GreenPolicy360 Archive Highlights 2013

- GreenPolicy360 Archive Highlights 2014

- GreenPolicy360 Archive Highlights 2015

- GreenPolicy360 Archive Highlights 2016

- GreenPolicy360 Archive Highlights 2017

- GreenPolicy360 Archive Highlights 2018

- GreenPolicy360 Archive Highlights 2019

- GreenPolicy360 Archive Highlights 2020

- GreenPolicy360 Archive Highlights 2023

Media in category "Voting Rights"

The following 66 files are in this category, out of 66 total.

- American Legislative Exchange Council.jpg 646 × 143; 41 KB

- At Poynter, St Petersburg, Florida.png 640 × 345; 555 KB

- Battle for Democracy.jpg 640 × 123; 24 KB

- Bernie Sanders, Senate 2.PNG 800 × 517; 379 KB

- Bernie Sanders, Senate Aug 3.PNG 800 × 518; 388 KB

- Biden - will we choose democracy.png 448 × 168; 30 KB

- Biden delivers voting rights speech in Atlanta.png 600 × 679; 387 KB

- Biden voting rights speech attacked by McConnell.png 600 × 321; 142 KB

- Biden voting rights support fading.png 600 × 682; 386 KB

- Black Lives Matter - St. Pete FL.jpg 800 × 806; 174 KB

- Cassidy Hutchinson testifies at Congressional committee hearing.png 640 × 447; 200 KB

- Citizens Climate Lobby - Save Our Future Act 2021.jpg 518 × 262; 77 KB

- Democracy Docket - June 2023.png 559 × 480; 383 KB

- Donald Trump criminally charged in Miami, Florida - CNN.png 640 × 518; 589 KB

- EleanorRooseveltHumanRights.png 535 × 423; 60 KB

- ElectionResources.png 607 × 243; 141 KB

- Electoral Count Reform Act - US, Brennan Center 2023.png 749 × 1,611; 339 KB

- Electoral Reform US FairVote.jpg 662 × 270; 36 KB

- Ginsburg leaves a chasm on the Supreme Court.jpg 800 × 624; 92 KB

- Gov and money.jpg 240 × 210; 7 KB

- GP360 tagcloud2 m.png 531 × 324; 132 KB

- GreenPartyPlatform 2000 KV10.png 338 × 531; 25 KB

- GreenPolicy360 - May- 9-2024.png 800 × 406; 119 KB

- Hannah Arendt.jpg 527 × 680; 51 KB

- Jan. 6 final report - news 1.png 600 × 693; 280 KB

- Jan. 6 final report - news 2.png 600 × 584; 260 KB

- January 6 committee - on December 19 2022.png 640 × 468; 591 KB

- January 6 committee final hearing - news.png 600 × 661; 343 KB

- January 6 committee votes to issue criminal referrals against Trump.png 800 × 204; 458 KB

- June 28 2022.png 800 × 565; 300 KB

- Liberty 180x180.png 180 × 180; 71 KB

- Living Democracy.png 787 × 600; 867 KB

- Manual Audits needed.png 557 × 480; 148 KB

- Money in Politics - PoliticoPay.png 491 × 226; 31 KB

- Money in Politics-System Failure-JLawrence Vid 2019.jpg 496 × 501; 44 KB

- Moore v Harper - attorneys.png 480 × 504; 156 KB

- No way nuclear codes being handed back to him.png 494 × 800; 106 KB

- OhClarence - Google News - Aug 10, 2023.png 800 × 856; 391 KB

- OhClarence 2 - Google News - Aug 10, 2023.png 800 × 819; 461 KB

- OhClarence 3 - Google News - Aug 10, 2023.png 800 × 842; 473 KB

- OhClarence 4- Google News - Aug 10, 2023.png 800 × 853; 491 KB

- One year later...I will defend this nation Jan-6-2022.png 513 × 364; 238 KB

- Point of View of the Acceptance Speech.png 600 × 771; 687 KB

- President Biden - January 5, 2024.png 600 × 470; 236 KB

- President Biden speaks of protecting democracy - Jan 5 2024.png 600 × 686; 214 KB

- President Biden speaks of protecting democracy - News on Jan 5 2024.png 600 × 664; 351 KB

- Project 2025 - Russell Vought and Donald Trump (AP).png 600 × 631; 453 KB

- Protect Democracy.png 775 × 600; 727 KB

- RBG as mom.jpg 320 × 320; 11 KB

- RBG as student.jpg 480 × 600; 27 KB

- RBG at Harvard Law School.jpg 640 × 942; 42 KB

- Richard Jacobs and The Man in the Arena - on July 4 2022.png 800 × 380; 192 KB

- Roosevelt and Muir at Yosemite.png 503 × 694; 686 KB

- SCOTUS-and the curtain re ABA.jpg 800 × 401; 152 KB

- Story telling and science education.png 515 × 480; 171 KB

- The Great Hack.jpg 640 × 395; 73 KB

- The Oath and the Office.png 572 × 480; 151 KB

- Totalitarianism in the Age of Trump, Lessons from Hannah Arendt.png 638 × 644; 143 KB

- Trump on Termination of US Constitution - 1.jpg 600 × 607; 166 KB

- Trump on Termination of US Constitution - 2.jpg 600 × 600; 181 KB

- Trump on Termination of US Constitution - 3.PNG 600 × 600; 227 KB

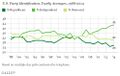

- US Party Identification 88 to 14.jpg 494 × 314; 27 KB

- Voting Wars.jpg 220 × 347; 80 KB

- Women right to vote years.png 800 × 529; 423 KB

- Your vote.png 318 × 133; 11 KB

- Legislation

- Topic

- Ballot Access

- Ballot Initiatives

- Ballot Measures

- Campaign Finance

- Civil Rights

- Climate Policy

- Corporate Accountability

- Election Law

- Election System Reform

- Electoral System Reform

- Environmental Laws

- EOS eco Operating System

- Green Politics

- Green Values

- Human Rights

- Initiative and Referendum

- Initiatives

- Money in Politics

- Participatory Governance

- Planet Citizen

- Redistricting

- Sustainability Policies

- United States

- US

- Voting

- Voting Systems

- Workers Rights