Bill McKibben, planet citizen: Difference between revisions

Siterunner (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Siterunner (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

<big><big>'''''2022'''''</big></big> | <big><big>'''''2022'''''</big></big> | ||

GreenPolicy360: Here, from Bill's new start-up on Substack. Consider joining his latest endeavor. His thoughts, described by Bill in this Sept 16, 2022 post he describes as 'a little bit of a rant', we re-publish the piece in whole (with a few added links about the Patagonia contribution) and ask our GreenPolicy readers to consider sharing Bill's thoughts to your network ... | |||

GreenPolicy360 Siterunner: Our old friend Bill McKibben is now 'officially' moving into the 'Third Act' and we are wishing him and the new organization success. | |||

<big><big>'''''What Planet Do I Live On?'''''</big></big> | |||

* https://billmckibben.substack.com/p/what-planet-do-i-live-on | |||

''By Bill McKibben'' | |||

''September 16, 2022'' | |||

''Yesterday, Rep. Ro Khanna’s energy subcommittee of the House Oversight and Reform Subcommittee released a tranche of documents from various Big Oil companies, designed in part to build support for a windfall profits tax on the huge sums that these firms have sucked in this year thanks to Vladimir Putin’s war. The documents show how mercenary and devious the companies have been, pretending to back climate action like the Paris climate accords but in fact working to make sure they are a dead letter.'' | |||

''But I confess I got stuck on the very first document the committee released, which you can see above. I got stuck because it’s…about me, and who doesn’t, in their heart of hearts, love/hate reading what people secretly think of you? '' | |||

''From what one can decipher from the email chain, a woman named Virginia Northington, who once had worked for the great historian Douglas Brinkley, later joined something called the Brunswick Group which “helps companies navigate a complex array of societal challenges, as well as articulating a company’s ‘purpose,’” and whose “Climate Hub helps businesses respond to climate change.” There Ms. Northington went to work “advis[ing] American, British, and European clients on litigation and crisis mandates,” which in the spring of 2016 (i.e. right after the Paris climate accords) apparently meant clipping out opeds from me and forwarding them to a long list of BP executives. One of those executives, Robert Stout, now a vice-president for regulatory policy and advocacy, responded that the Los Angeles Times essay she’d passed around was a “must-read,” which is a nice thing to say but I don’t think he meant it that way. One of his employees, the director of communications and external affairs, responded in more heartfelt fashion. As Mr. Tom Wolf wrote to a long list of colleagues as follows:'' | |||

:''I'm sorry, I live on earth so I don't get what planet this guy lives on. We all know his diatribe has many holes in it...but his biggest one is the infrastructure piece. Americans are fighting pipelines, but they are also fighting transmission lines that would bring wind energy and solar energy to market....they are fighting utility solar farms in the desert because it affects the desert turtle, they are fighting home solar that looks ugly. Simply put, Americans have a Dire Straits mentality. They want their money for nothin' and their chicks for free...'' | |||

''For the record, as readers of this newsletter know, this is one issue where I’m not a hypocrite. I fight for solar even if someone thinks it looks ugly , and I’ve been doing it for a long time. And in fact my home has solar panels all over the top, and on a couple of poles in the yard—they’re not as pretty as the surrounding trees, except when you think about what they mean, which is that we can now get the energy we need from the sun instead of, say, ripping a hole in the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico which then leaks for six months in what was the largest oil spill ever.'' | |||

''But it was Wolf’s language that really got me thinking. “I don’t get what planet this guy lives on,” he asks, and so let me answer.'' | |||

''I live on a different planet than the one I was born on. That one had plenty of ice at each pole, and lots of coral reefs in between. The great glaciers of the Alps and the Himalayas and the Andes were locked in icy grandeur; the seasons, in my home parts, stretched on as they had for millennia, ever since the retreat of the last Ice Age.'' | |||

''But now I live on a planet—I called it Eaarth once, in the title of a book—that looks somewhat like that old one, but is irrevocably changed. The first pictures we ever took of it, the ones that came back from the Apollo missions, are now hopelessly out of date: there’s a lot less white and a lot more blue up top because most of the sea ice in the summer Arctic is gone. The pH of the oceans on this new planet is different, and so is the chemical composition of the atmosphere: the air now holds much higher concentrations of carbon dioxide and methane, and as a result the temperature has gone well beyond what humans have ever experienced before. On this planet people starve—right now, this year—because it doesn’t rain anymore where they live, and they go hungry because it rains more than it’s ever rained before. On this planet the sea level has begun to climb, threatening to wipe out entire nations. On this planet tens of millions of our brothers and sisters are already on the move, because they can no longer live in the places where they were born.'' | |||

''It’s a deeply unjust planet, because the people who caused the temperature to rise are not usually the people who suffer the most from that rise. And it’s an arguably insane planet, because so many of the people who run it ignored for decades the clear warning of scientists that we faced a stiff but surmountable challenge. Worse than ignored—the leaders of the fossil fuel industry, at the time the biggest and richest industry on the planet, suppressed and denied the truth. Few were more disgusting about it than BP, which originally sought to rebrand itself as Beyond Petroleum (doubtless advised by someone like the Brunswick Group) and then decided that wasn’t making enough money so they dropped the idea and returned to just plain old Petroleum. It invested heavily in shale fracking, and in Alberta’s tar sands, literally the dirtiest possible oil.'' | |||

''But it’s also a planet filled with remarkable people, who have rallied by their millions to stand up to people like Mr. Wolf, trying in the process to write a new future for this planet. While he’s sat around commenting sardonically on opeds, they’ve marched, gone to jail, and often won (when they beat the Keystone pipeline, they cost those tarsands investments real money). There are far more of us then there are of him; in a world where BP’s billions didn’t buy politicians, we’d have long since won these fights.'' | |||

''And we will win those battles, or at least keep trying. Because we live on a planet that, though degraded by the greed of Big Oil, still has such heart-searing beauty. It’s a world where creeks still tumble down mountainsides, where trees still spread their branches to make shade in the heat, where hummingbirds and anteaters remind us of the whimsy of evolution, where people love and protect each other, family and strangers both. It’s a good world still, and worth the defending. Complex, buzzing, cruel, mysterious, sexy, alive. For a while yet anyway, no thanks to BP. | |||

Oh, and Dire Straits? I mean, come on. Just because you flak for an oil company doesn’t mean you can’t find someone with a bit more groove to frame your social commentary. Let me nominate Mr. Marvin Gaye, who might have been thinking of BP when he wrote lyrics considerably more immortal than anything from the Knopfler brothers.'' | |||

:''Ah, things ain't what they used to be'' | |||

:''Where did all the blue skies go?'' | |||

:''Poison is the wind that blows'' | |||

:''From the north and south and east'' | |||

''End of rant. I’m glad they read what I write, and I’m glad they pass it around, and I’m glad that it scares them and makes them sad. I’ll keep at it.'' | |||

''In other climate and energy news this week:'' | |||

''+ A landmark new report from the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis looks at carbon capture projects around the world and finds they…don’t work. Instead:'' | |||

''• Failed/underperforming projects considerably outnumbered successful experiences.'' | |||

''• Captured carbon has mostly been used for enhanced oil recovery (EOR): enhancing oil production is not a climate solution.'' | |||

''• Using carbon capture as a greenlight to extend the life of fossil fuels power plants is a significant financial and technical risk: history confirms this.'' | |||

''+ David Wallace-Wells is really using his new platform at the New York Times to advance critical parts of the climate story, and this week’s coverage of China is no exception:'' | |||

''China also seems to occupy a confusing place in the landscape of climate geopolitics because that landscape has shifted lately as well. Ten years ago, or even five, climate diplomacy often meant rhetorical appeals to global cooperation mixed with realpolitik efforts to move more slowly than your rivals. Today, decarbonization is still happening much too slowly, but fast enough to move the diplomatic dynamics away from a rivalry of inaction toward an apparent rivalry of action. Climate investment is booming in the United States, and with the CHIPS act and the I.R.A. climate bill now passed into law, the country has affirmatively joined what Politico recently called a new “green-energy arms race.”'' | |||

''+ A group of blue-state treasurers have against efforts by their fossil-fueled counterparts to limit environmentally responsible investing:'' | |||

''The blacklisting states apparently believe, despite ample evidence and scientific consensus to the contrary, that poor working conditions, unfair compensation, discrimination and harassment, and even poor governance practices do not represent material threats to the companies in which they invest. They refuse to acknowledge, in the face of sweltering heat, floods, tornadoes, snowstorms and other extreme weather, that climate change is real and is a true business threat to all of us.'' | |||

''We disagree. Disclosure, transparency, and accountability make companies more resilient by sharpening how they manage, ensuring that they are appropriately planning for the future. Our work, alongside those of other investors, employees, and customers have caused many companies to evolve their business models and their internal processes, better addressing the long term material risks that threaten their performance.'' | |||

and... | |||

''+ Yvon Chouinard is an awfully good guy. Thanks!'' | |||

(WaPo) ''Patagonia founder gives away company: ‘Earth is now our only shareholder’: Ownership of the company, founded in 1973 and reportedly valued at about $3 billion, has been transferred to a trust created to protect the firm’s values, as well as a nonprofit organization'' | (NYT) ''Patagonia Founder Gives Away the Company to Fight Climate Change'' | |||

* https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-solutions/2022/09/14/patagonia-yvon-chouinard-climate-change/ | |||

* https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/14/climate/patagonia-climate-philanthropy-chouinard.html | |||

and... | |||

''+ It was the hottest summer on record for Europe and for China.'' | |||

(GreenPolicy360) Follow the Data | |||

* https://www.greenpolicy360.net/w/Too_Hot | |||

* https://www.greenpolicy360.net/w/File:Good_science_needs_good_data_.png | |||

········································ | |||

GreenPolicy360 Siterunner: | |||

Our old friend Bill McKibben is now 'officially' moving into the 'Third Act' and we are wishing him and the new organization success. | |||

Take a look at his new start up ! | Take a look at his new start up ! | ||

Revision as of 17:03, 17 September 2022

"The Question I Get Asked the Most?" The most common one by far is also the simplest: 'What can I do?' I bet I've been asked it 10,000 times by now... 'What can I do to make a difference?' The right question is 'What can we do to make a difference?' " -- Bill McKibben

2022

GreenPolicy360: Here, from Bill's new start-up on Substack. Consider joining his latest endeavor. His thoughts, described by Bill in this Sept 16, 2022 post he describes as 'a little bit of a rant', we re-publish the piece in whole (with a few added links about the Patagonia contribution) and ask our GreenPolicy readers to consider sharing Bill's thoughts to your network ...

What Planet Do I Live On?

By Bill McKibben

September 16, 2022

Yesterday, Rep. Ro Khanna’s energy subcommittee of the House Oversight and Reform Subcommittee released a tranche of documents from various Big Oil companies, designed in part to build support for a windfall profits tax on the huge sums that these firms have sucked in this year thanks to Vladimir Putin’s war. The documents show how mercenary and devious the companies have been, pretending to back climate action like the Paris climate accords but in fact working to make sure they are a dead letter.

But I confess I got stuck on the very first document the committee released, which you can see above. I got stuck because it’s…about me, and who doesn’t, in their heart of hearts, love/hate reading what people secretly think of you?

From what one can decipher from the email chain, a woman named Virginia Northington, who once had worked for the great historian Douglas Brinkley, later joined something called the Brunswick Group which “helps companies navigate a complex array of societal challenges, as well as articulating a company’s ‘purpose,’” and whose “Climate Hub helps businesses respond to climate change.” There Ms. Northington went to work “advis[ing] American, British, and European clients on litigation and crisis mandates,” which in the spring of 2016 (i.e. right after the Paris climate accords) apparently meant clipping out opeds from me and forwarding them to a long list of BP executives. One of those executives, Robert Stout, now a vice-president for regulatory policy and advocacy, responded that the Los Angeles Times essay she’d passed around was a “must-read,” which is a nice thing to say but I don’t think he meant it that way. One of his employees, the director of communications and external affairs, responded in more heartfelt fashion. As Mr. Tom Wolf wrote to a long list of colleagues as follows:

- I'm sorry, I live on earth so I don't get what planet this guy lives on. We all know his diatribe has many holes in it...but his biggest one is the infrastructure piece. Americans are fighting pipelines, but they are also fighting transmission lines that would bring wind energy and solar energy to market....they are fighting utility solar farms in the desert because it affects the desert turtle, they are fighting home solar that looks ugly. Simply put, Americans have a Dire Straits mentality. They want their money for nothin' and their chicks for free...

For the record, as readers of this newsletter know, this is one issue where I’m not a hypocrite. I fight for solar even if someone thinks it looks ugly , and I’ve been doing it for a long time. And in fact my home has solar panels all over the top, and on a couple of poles in the yard—they’re not as pretty as the surrounding trees, except when you think about what they mean, which is that we can now get the energy we need from the sun instead of, say, ripping a hole in the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico which then leaks for six months in what was the largest oil spill ever.

But it was Wolf’s language that really got me thinking. “I don’t get what planet this guy lives on,” he asks, and so let me answer.

I live on a different planet than the one I was born on. That one had plenty of ice at each pole, and lots of coral reefs in between. The great glaciers of the Alps and the Himalayas and the Andes were locked in icy grandeur; the seasons, in my home parts, stretched on as they had for millennia, ever since the retreat of the last Ice Age.

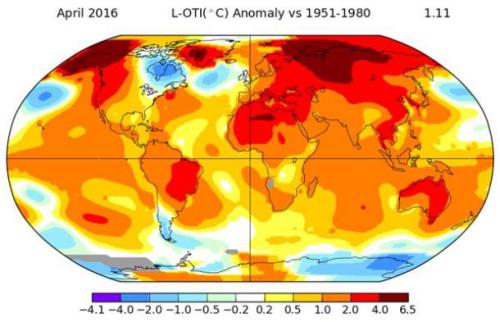

But now I live on a planet—I called it Eaarth once, in the title of a book—that looks somewhat like that old one, but is irrevocably changed. The first pictures we ever took of it, the ones that came back from the Apollo missions, are now hopelessly out of date: there’s a lot less white and a lot more blue up top because most of the sea ice in the summer Arctic is gone. The pH of the oceans on this new planet is different, and so is the chemical composition of the atmosphere: the air now holds much higher concentrations of carbon dioxide and methane, and as a result the temperature has gone well beyond what humans have ever experienced before. On this planet people starve—right now, this year—because it doesn’t rain anymore where they live, and they go hungry because it rains more than it’s ever rained before. On this planet the sea level has begun to climb, threatening to wipe out entire nations. On this planet tens of millions of our brothers and sisters are already on the move, because they can no longer live in the places where they were born.

It’s a deeply unjust planet, because the people who caused the temperature to rise are not usually the people who suffer the most from that rise. And it’s an arguably insane planet, because so many of the people who run it ignored for decades the clear warning of scientists that we faced a stiff but surmountable challenge. Worse than ignored—the leaders of the fossil fuel industry, at the time the biggest and richest industry on the planet, suppressed and denied the truth. Few were more disgusting about it than BP, which originally sought to rebrand itself as Beyond Petroleum (doubtless advised by someone like the Brunswick Group) and then decided that wasn’t making enough money so they dropped the idea and returned to just plain old Petroleum. It invested heavily in shale fracking, and in Alberta’s tar sands, literally the dirtiest possible oil.

But it’s also a planet filled with remarkable people, who have rallied by their millions to stand up to people like Mr. Wolf, trying in the process to write a new future for this planet. While he’s sat around commenting sardonically on opeds, they’ve marched, gone to jail, and often won (when they beat the Keystone pipeline, they cost those tarsands investments real money). There are far more of us then there are of him; in a world where BP’s billions didn’t buy politicians, we’d have long since won these fights.

And we will win those battles, or at least keep trying. Because we live on a planet that, though degraded by the greed of Big Oil, still has such heart-searing beauty. It’s a world where creeks still tumble down mountainsides, where trees still spread their branches to make shade in the heat, where hummingbirds and anteaters remind us of the whimsy of evolution, where people love and protect each other, family and strangers both. It’s a good world still, and worth the defending. Complex, buzzing, cruel, mysterious, sexy, alive. For a while yet anyway, no thanks to BP. Oh, and Dire Straits? I mean, come on. Just because you flak for an oil company doesn’t mean you can’t find someone with a bit more groove to frame your social commentary. Let me nominate Mr. Marvin Gaye, who might have been thinking of BP when he wrote lyrics considerably more immortal than anything from the Knopfler brothers.

- Ah, things ain't what they used to be

- Where did all the blue skies go?

- Poison is the wind that blows

- From the north and south and east

End of rant. I’m glad they read what I write, and I’m glad they pass it around, and I’m glad that it scares them and makes them sad. I’ll keep at it.

In other climate and energy news this week:

+ A landmark new report from the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis looks at carbon capture projects around the world and finds they…don’t work. Instead:

• Failed/underperforming projects considerably outnumbered successful experiences. • Captured carbon has mostly been used for enhanced oil recovery (EOR): enhancing oil production is not a climate solution. • Using carbon capture as a greenlight to extend the life of fossil fuels power plants is a significant financial and technical risk: history confirms this.

+ David Wallace-Wells is really using his new platform at the New York Times to advance critical parts of the climate story, and this week’s coverage of China is no exception:

China also seems to occupy a confusing place in the landscape of climate geopolitics because that landscape has shifted lately as well. Ten years ago, or even five, climate diplomacy often meant rhetorical appeals to global cooperation mixed with realpolitik efforts to move more slowly than your rivals. Today, decarbonization is still happening much too slowly, but fast enough to move the diplomatic dynamics away from a rivalry of inaction toward an apparent rivalry of action. Climate investment is booming in the United States, and with the CHIPS act and the I.R.A. climate bill now passed into law, the country has affirmatively joined what Politico recently called a new “green-energy arms race.”

+ A group of blue-state treasurers have against efforts by their fossil-fueled counterparts to limit environmentally responsible investing:

The blacklisting states apparently believe, despite ample evidence and scientific consensus to the contrary, that poor working conditions, unfair compensation, discrimination and harassment, and even poor governance practices do not represent material threats to the companies in which they invest. They refuse to acknowledge, in the face of sweltering heat, floods, tornadoes, snowstorms and other extreme weather, that climate change is real and is a true business threat to all of us.

We disagree. Disclosure, transparency, and accountability make companies more resilient by sharpening how they manage, ensuring that they are appropriately planning for the future. Our work, alongside those of other investors, employees, and customers have caused many companies to evolve their business models and their internal processes, better addressing the long term material risks that threaten their performance.

and...

+ Yvon Chouinard is an awfully good guy. Thanks!

(WaPo) Patagonia founder gives away company: ‘Earth is now our only shareholder’: Ownership of the company, founded in 1973 and reportedly valued at about $3 billion, has been transferred to a trust created to protect the firm’s values, as well as a nonprofit organization | (NYT) Patagonia Founder Gives Away the Company to Fight Climate Change

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-solutions/2022/09/14/patagonia-yvon-chouinard-climate-change/

and...

+ It was the hottest summer on record for Europe and for China.

(GreenPolicy360) Follow the Data

········································

GreenPolicy360 Siterunner:

Our old friend Bill McKibben is now 'officially' moving into the 'Third Act' and we are wishing him and the new organization success.

Take a look at his new start up !

Third Act

Here's how Third Act describes their mission ...

Why Third Act

“Experienced Americans” are the fastest-growing part of the population: 10,000 people a day pass the 60-year mark. That means that there’s no way to make the changes that must be made to protect our planet and our society unless we bring the power of this group into play.

We’re used to thinking that humans grow more conservative as they age, perhaps because we have more to protect, or simply because we’re used to things the way they are. But our generations saw enormous positive change early in our lives—the civil rights movement, for instance, or the fight to end massive wars or guarantee the rights of women. And now we fear that the promise of those changes may be dying, as the planet heats and inequality grows.

But as a generation we have unprecedented skills and resources that we can bring to bear. Washington and Wall Street have to listen when we speak, because we vote and because we have a large—maybe an overlarge—share of the country’s assets. And many of us have kids and grandkids and great grandkids: we have, in other words, very real reasons to worry and to work.

Third Act is people over the age of 60 — “experienced Americans” — determined to change the world for the better. We muster political and economic power to move Washington and Wall Street in the name of a fairer, more sustainable society and planet. We back up the great work of younger people, and we make good trouble of our own.

Together we will campaign on issues of climate change, racial equity, and the protection of democracy. These represent some of the unfinished business of our lifetimes.

🌎

The Third Act mission statement makes sense to us at GreenPolicy360. When we reach our olden years, we stay engaged, connected and continue "to make a positive difference" ...

- Each of us can make a positive difference stepping up & doing our best / Becoming Planet Citizens

·······························································

On Earth Day, April 22, 2022

From #PlanetCitizen Bill McKibben

Let’s note that Earth Day was born in 1970 not as a celebration, and not as an occasion for greenwashing press releases, and not as a moment for photo ops—but as a honking big protest. Maybe the biggest protest in American history—by some estimates there were 20 million Americans on the street April 22, 1970, which would have been about ten percent of the then-American population. -- Bill McKibben | https://billmckibben.substack.com/p/earth-day-is-a-time-foranger

Memories of Setting in Motion the First Earth Day in 1970

From Steve Schmidt, founder GreenPolicy360

·································································································································

···························

August 2021

···························

June 2021

···························

April 2021

Solar Energy Price Revolution by Bill McKibben

April 29, 2021 / excerpted from The New Yorker

Earth Week has come and gone, leaving behind an ankle-deep and green-tinted drift of reports, press releases, and earnest promises from C.E.O.s and premiers alike that they are planning to become part of the solution. There were contingent signs of real possibility—if some of the heads of state whom John Kerry called on to make Zoom speeches appeared a little strained, at least they appeared. (Scott Morrison, the Prime Minister of Australia, the most carbon-emitting developed nation per capita, struggled to make his technology work.) But, if you want real hope, the best place to look may be a little noted report from the London-based think tank Carbon Tracker Initiative.

Titled “The Sky’s the Limit,” it begins by declaring that “solar and wind potential is far higher than that of fossil fuels and can meet global energy demand many times over.” Taken by itself, that’s not a very bold claim: scientists have long noted that the sun directs more energy to the Earth in an hour than humans use in a year. But, until very recently, it was too expensive to capture that power. That’s what has shifted—and so quickly and so dramatically that most of the world’s politicians are now living on a different planet than the one we actually inhabit. On the actual Earth, circa 2021, the report reads, “with current technology and in a subset of available locations we can capture at least 6,700 PWh p.a. [petawatt-hours per year] from solar and wind, which is more than 100 times global energy demand.” And this will not require covering the globe with solar arrays: “The land required for solar panels alone to provide all global energy is 450,000 km2, 0.3% of the global land area of 149 million km2. That is less than the land required for fossil fuels today, which in the US alone is 126,000 km2, 1.3% of the country.” These are the kinds of numbers that reshape your understanding of the future.

We haven’t yet fully grasped this potential because it’s happened so fast. In 2015, zero per cent of solar’s technical potential was economically viable—the small number of solar panels that existed at that time had to be heavily subsidized. But prices for solar energy have collapsed so fast over the past three years that sixty per cent of that potential is already economically viable. And, because costs continue to slide with every quarter, solar energy will be cheaper than fossil fuels almost everywhere on the planet by the decade’s end. (It’s a delicious historical irony that this evolution took place, entirely by coincidence, during the Administration of Donald Trump, even as he ranted about how solar wasn’t “strong enough” and was “very, very expensive.”) The Carbon Tracker report, co-written by Kingsmill Bond, is full of fascinating points, such as how renewable energy is the biggest gift of all for some of the poorest nations, including in Africa, where solar potential outweighs current energy use by a factor of more than a thousand. Only a few countries—Singapore, Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and a handful of European countries—are “stretched” in their ability to rely on renewables, because they both use a lot of energy and have little unoccupied land. In these terms, Germany is in the third-worst position, and the fact that it is nonetheless one of the world’s leaders in renewable energy should be a powerful signal: “If the Germans can find solutions, then so can everyone else.”

The numbers in the report are overwhelming—even if the analysts are too optimistic by half, we’ll still be swimming in cheap solar energy. “We have established that technical and economic barriers have been crossed by falling costs. It follows that the main remaining barrier to change is the ability of incumbents to manipulate political forces to stop change,” the report reads. Indeed. And the problem is that we need that change to happen right now, because the curves of damage from the climate crisis are as steep as the curves of falling solar prices. Given three or four decades, economics will clearly take care of the problem—the low price of solar power will keep pushing us to replace liquid fuels with electricity generated from the sun, and, eventually, no one will have a gas boiler in the basement or an internal-combustion engine in the car. But, if the transition takes three or four decades, no one will have an ice cap in the Arctic, either, and everyone who lives near a coast will be figuring out where on earth to go.

Change is hard. The job of politicians is to make it easier for those affected, so that what must happen can happen—and within the time we’ve been allotted by physics. But that hard job is infinitely easier now that renewable energy is suddenly so cheap. The falling price puts the wind at our backs, as it were. It’s the greatest gift we could have been given as a civilization, and we dare not waste it.

···························

December 2020

Bill McKibben, Planet Citizen

Once in a while, it’s important to pull back and try to put it all in perspective. Now is such a time: this month marks the fifth anniversary of the Paris climate summit; we’ve more or less survived the Trump Administration, with an incoming Administration promising a new approach; and we’re less than a year away from what will be the next great global climate meeting, in Glasgow, Scotland. (On a personal note, I’m subsiding into emeritus status at 350.org, the climate campaign I helped found, and I turn sixty this week—since I started writing my first book about all this when I was twenty-seven, this milestone means that I’ve spent four-fifths of my adult life wrestling with the climate problem.) Where do we stand? Take a deep breath.

All discussions of the climate crisis start with science, and the science is grim. Despite a La Niña wave cooling the global temperature in 2020, this year will vie for the hottest on record. It’s already seen what could be the highest temperature ever reliably recorded (a hundred and thirty degrees, in California), devastating wildfires in Australia, Siberia, the American West, and South America, where about a quarter of the Pantanal, the largest wetland on earth, burned. Thirty named storms formed in the Atlantic, leading to a record hurricane season.

But those dramatic moments obscure the more devastating and silent changes....

To put it simply, the temperature is increasing steadily and at a pace scientists had predicted. (The latest figures from Columbia University’s James Hansen and other climate scientists suggest an acceleration of warming over the past few years.) “We have entered a new climate,” the meteorologist Jeff Masters, a contributor to Yale Climate Connections, said last week. “Heat is energy and when everything else comes together,” he added, “things are going to go bonkers.”

···························

June 2020

"The Vatican's call for divestment is a breath of hope in times when faith is more needed than ever," said 350.org co-founder Bill McKibben. "It is a powerful statement that attempting to profit off the destruction of the planet is plainly and simply immoral and unethical."

···························

May 2020

Via The Guardian / 7 May 2020 / by George Monbiot @GeorgeMonbiot

Review of Planet of the Humans, and its attacks on environmental activists

Planet of the Humans concentrates its attacks on Bill McKibben, the co-founder of 350.org, who takes no money from any of his campaigning work. It’s an almost comic exercise in misdirection, but unfortunately it has horrible, real-world consequences, as McKibben now faces even more threats and attacks than he confronted before.

···························

April 2020

Bill McKibben, interviewed for Earth Day by DemocracyNow

- ············································································································

Bill McKibben chats with Boston Councilor Michelle Wu on COVID19, economic inequalities, climate change and solutions going forward...

·············································································

Turning the Page: We Go On To the Work in Front of Us

2020: Another Decade

···························

December 2019

Reflecting on the past 30 years of climate change: With Bill McKibben at the Bioneers Conference

Video, Introduced by Kenny Ausubel

·······················································

Bill McKibben, GreenPolicy360's former adviser, writes of climate change/global warming and the existential threat we all face

If the world ran on sun, it wouldn’t fight over oil

By Bill McKibben / Via The Guardian

The climate crisis isn’t the only reason to kick fossil fuels

Wed 18 Sep 2019 01.01 EDT

We are sadly accustomed by now to the idea that our reliance on oil and gas causes random but predictable outbreaks of flood, firestorm and drought. The weekend’s news from the Gulf is a grim reminder that depending on oil leads inevitably to war too.

Depending on how far back you want to stand, the possibility of war with Iran stems from a calculated decision by Tehran or its Houthi allies to use drones and missiles on Saudi installations, or on the infantile rage that drove President Trump to tear up a meticulously worked out and globally sponsored accord with Iran and to wreck its economy. But in either case, if you really take in the whole picture, the image is rendered in crude, black tones: were it not for oil, none of this would be happening.

Were it not for oil, the Middle East would not be awash in expensive weapons; its political passions would matter no more to the world than those of any other corner of our Earth. Were it not for oil, we would not be beholden to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia – indeed, we might be able to bring ourselves to forthrightly condemn its savagery. Were it not for oil, we would never have involved ourselves in a ruinous war with Iraq, destabilising an entire region. (I remember the biting slogan on a sign from an early protest against the war with Saddam Hussein: “How did our oil end up under their sand?”)

Conveniently, the largest ever demonstrations about energy policy are scheduled to take place this Friday: Global Climate Strike, Find Your Local Strike Event

We’ve come to take for granted that this is how the world works. Within hours of the pictures of devastated oilfields, we had “explainers” from our various news outlets reminding us of the realities of our predicament: with Aramco largely offline, the world’s spare capacity was mostly gone. Hence oil prices would spike upwards. Hence there would be damage to the world’s economy. Reporters quoted gloating Revolutionary Guards from Iran and concerned Opec officials, and stock analysts waiting breathlessly to see how Wall Street would react. The drama seemed choreographed because we’ve seen it so often that everyone knows their parts.

But this iteration of the opera is different in one way. An unspoken truth hangs over the whole predictable scene: this will be the first oil war in an age when we widely recognise that we needn’t depend on oil any longer.

The last time we started down this path, in Iraq more than 15 years ago, a solar panel cost 10 times what it does today. Wind power was still in its infancy. No one you knew had ever driven an electric car. Today the sun and the breeze are the cheapest ways to generate power on our Earth, and Chinese factories are churning out electric vehicles. That is to say, we have the technology available to us that would render this kind of warmongering transparently absurd even to the most belligerent soul.

We haven’t come close to fully deploying that technology, of course –and unlike 15 years ago we understand why. Thanks to great investigative reporting, we now know that the oil industry knew all about climate change decades ago, but instead of acknowledging it and helping us move to a new energy future, they instead spent billions building the scaffolding of deceit and denial and disinformation that kept us locked in the present paradigm. Just as they have profited from sea-level rise and Arctic melt, so they will profit from the war now starting to unfold. (Right on schedule, the share prices of fracking firms and oil majors all jumped perkily northwards on Monday morning.)

If it happens, this war, like the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, will cost untold lives, most of them civilian. It will also, like those conflicts, cost trillions of dollars. Imagine if we had spent those trillions of dollars not on cruise missiles and up-armoured Humvees, but on solar farms and offshore wind turbines. Imagine if we’d stuck insulation in the walls of every building in the US, and built a robust network of electric vehicle chargers.

That’s not a fanciful vision – it’s exactly what legislation such as the Green New Deal envisions in the US – and indeed there are very similar proposals in the UK and Canada, and across the EU. But we are told that the Green New Deal is an impossibly expensive boondoggle – by precisely the same people now eager to pour blood and treasure down a hole in the desert. A trillion dollars spent on war returns nothing except trauma and misery; a trillion dollars spent on solar panels leaves behind a nation that gets its power for free each morning when the sun comes up.

That new world is coming – in fact, you can sense its arrival in the somewhat muted reaction to the oilfield drones and missiles. Yes, the price of oil “spiked”. But it’s still historically low, because the planet is awash with oil – and that’s in part because demand growth has begun to soften. The day will come when blocking the strait of Hormuzor blowing up a petrol station will be an empty threat – and that will be a good day indeed.

We can speed up that process immeasurably by pushing our politicians to act much faster on the transition to clean energy. There’s no mystery about the necessary steps. Big support for renewables, rigorous “keep it in the ground” policies, making polluters pay for the damage they’ve done: pretty much precisely the plansthe Democrats are rolling out as they campaign. But we need the will to make these things actually happen.

The world ignored the warning signs – and now the Middle East is on the brink | Simon Tisdall

Conveniently, the largest ever demonstrations about energy policy are scheduled to take place this Friday. The climate strikes touched off by Greta Thunberg and her young colleagues around the world go multigenerational on 20 September (you can find the closest ones to you at globalclimatestrike.net). They are designed to deal with the greatest existential threat humans have ever faced: the rapid heating of our Earth. But they also serve as a chance to say no to this and other oil wars. We have to do it fast – if we don’t, we’ll just go from fighting wars over oil to fighting wars over survival on a fast-degrading planet.

No one will ever fight a war over access to sunshine – what would a country do, set up enormous walls to shade everyone else’s panels? (Giant walls are hard to build – just ask Trump.) Fossil fuels are concentrated in a few places, giving those who live atop them enormous power; renewable energy can be found everywhere, the birthright of all humans. A world that runs on sun and wind is a world that can relax.

More from McKibben

Money is the oxygen on which global warming burns

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○

SJS / GreenPolicy360 Siterunner:

Bill McKibben is an amazing planet citizen and we greatly respect him for his strength of mind and his courage. Looking back to the GreenPolicy360 Green Institute/GreenPolicy beginnings, Bill was one of the most hard working members of our board of advisors. He was a force at a distance as he traveled in constant motion. His words were powerful, his far-flung work inspirational. Bill was imagining new direction as a writer-activist and imagining what could be and needed to be done to face environmental crisis.

This was in 2007 as a 'Great Recession' started a downward collapse and out of global economic shockwaves came ideas for a new economics. In the UK, a "Global New Deal" was rolled out as a way to move beyond recession with a forward-looking green economics plan to confront the crisis of climate change. In the US, the activism of Bill McKibben was envisioning what had to happen to confront the climate crisis. Bill's new organization with global networking was 'brain-stormed' and launched in 2008 as 350.org

A tip of our green hat to all planet citizens, adventurers, dreamers and doers who imagine what can be done, step up and act to make a positive difference.

Together we can change business-as-usual / #ActonClimate

It's Not on the Way, It's Here, the Crisis, Our New Climate Reality

Falter: Has the Human Game Begun to Play Itself Out? / Published April 2019 by Henry Holt and Co.

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○

(From Amazon: Bill McKibben is the author of The End of Nature, Deep Economy, and numerous other books. He is the founder of the environmental organizations Step It Up and 350.org, and was among the first to warn of the dangers of global warming.)

(From Wikipedia: William Ernest "Bill" McKibben (born December 8, 1960) is an American environmentalist, author, and journalist who has written extensively on the impact of global warming. He is the Schumann Distinguished Scholar at Middlebury College and leader of the anti-carbon campaign group 350.org. He has authored a dozen books about the environment, including his first, The End of Nature (1989), about climate change. More)

Environmental Writer Turns Words into Action / Via Voice of America (VOA)

Activist launches worldwide campaign to fight climate change / 2008 / https://350.org/about/#history

McKibben was born in 1960 in Lexington, Massachusetts, the birthplace of the American Revolution.

During his summers in high school, McKibben led tours on the Lexington battlefield telling the story of American democracy and freedom. He says the experience taught him a valuable history lesson.

Bill McKibben: "I've never confused dissent with the lack of patriotism; if anything, just the opposite. You know the people I was talking about showed their patriotism by dissenting from big power."

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○

Earth Day, 2018, Existential Challenges, Life on Earth

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○

Bill McKibben and Bill Moyers Talk

Bill Moyers: Sixteen books of first-rate journalism and now a novel. Your first. Did reality become too much for you?

Bill McKibben: ... I thought maybe it would be OK to indulge my funnier side a little bit, in the service of the resistance to all that’s happening around us.

Moyers: Explaining why you turned not just to fiction but to a fable. Fables are playful. Sometimes the truth goes down easier when it’s more playful.

McKibben: I’ve spent my life living in rural America, some of it in blue state Vermont, some of it in red state upstate New York. They’re quite alike in many ways. And quite wonderful. It’s important that even in an urbanized and suburbanized country, we continue to take rural America seriously. And the thing that makes Vermont in particular so special, and I hope this book captures some of it, is the basic underlying civility of its political life. That’s rooted in the town meeting. Each of the towns in Vermont governs itself...

McKibben: The consumer culture in general has washed over our civilization. And one result is that neighbors like these became optional in America. For the last 50 years, if you’ve had a credit card and some access to money, you don’t really need neighbors around you. And as a result, they dwindled. The average American has half as many close friends as they did in 1950. Three quarters of Americans don’t know their next-door neighbor. They may know their name, but they have no real relationship with them. That’s an utterly new place for human beings to find themselves in—I mean, we’re a socially evolved primate. It wasn’t that many generations ago that we were sitting on the savannah picking lice out of each other’s fur. It’s got to be one of the reasons that we’re going so crazy right now.

McKibben: I’m afraid rebellion comes naturally to me. You mentioned Concord and Lexington in Massachusetts. I grew up in Lexington. And I used to give summer tours of the Battle Green, the “birthplace of American liberty.” Really, Lexington marked the start of the worldwide battle against imperialism and colonialism, and I would put on my tricorn hat and go out and tell tourists about the beginning of that fight. So I’ve never in my life confused dissent with a lack of patriotism. Just the opposite, in many ways.

McKibben: No taxation without representation! How many of us feel truly represented? One of the ironies of this book is that Vermont in some ways should be the last place to secede from the Union. We come closer to having an effective democracy than anyplace. There’s 600,000 of us and we have two senators—Sanders and Leahy—and we can see them in the grocery store and call them on the phone. I can’t imagine why California settles for only two senators. It’s the sixth-largest economy in the world. It’s got 40 million people. And two senators, just as we have in Vermont. The idea of one man, one vote is increasingly crazy in this country, and so is the malignant effect of money on our political life, as you have been reporting a long time now.

McKibben: ... (O)ver the last 10 years. I’ve been a part of it with the organization 350.org, fighting global warming, and now in the resistance that’s sprung up in the last year since Donald Trump took over. That’s been the one heartening thing about this year: the antibodies have assembled themselves to try and fight off the fever that America’s now in. I’m no Pollyanna, so I don’t know if it’s going to work or not.

Moyers: Let’s pause right here and talk about this present moment as reality, not fable. Here’s what your story prompts me to ask: When people realize the current order of things no longer works and the institutions of government and society are failing to fix them—failing to solve the problems democracy creates for itself—what options do they have?

McKibben: Well, I don’t think we’re in a place where rebellion in the sense of the American Revolution works anymore. One of the reasons that I’m a big advocate of nonviolence is that it’s the only thing that makes sense...

McKibben: It’s harder with many other things. The fight around climate change, which I’ve spent my life on, is somewhat more difficult because no one makes trillions of dollars a year being a bigot, and that’s how much the fossil-fuel industry pulls in pumping carbon into the air. But the principle is the same, I think.

Moyers: For me the question now is how much time do we have? When it comes to global warming, all signs suggest we are running out of time.

McKibben: The question of time is the question that haunts me. I remain optimistic enough to think that in general human beings will figure out the right thing to do eventually, and Americans will somehow get back on course. Of course, there’ll be a lot of damage done in the meantime. But with climate change in particular—the gravest of the problems we face—time is the one thing we don’t have. It’s the only problem we’ve ever had that came with a time limit. And if we don’t solve it soon, we don’t solve it. Our governments so far have not proven capable of dealing with this question. They simply haven’t been able to shake off the self-interest and massive power of the fossil-fuel industry. It’s going to take a lot of work and a lot of effort to get us onto renewable energy quickly and everywhere. It’s doable technically; the question is whether it’s doable politically or not. There I don’t know.

Moyers: You’ve said that winning slowly in this fight —

McKibben: Winning slowly is another way of losing. Look, we’re screwing up our health care system again right now. That’s going to cause grave trouble for people over the next five, 10 years. There are going to be lots of people who die, lots of people who are sick, lots of people who go bankrupt. It’s going to be horrible. But 10 years from now it will not be harder to solve the problem because you ignored it for those 10 years. It won’t have changed into some completely other problem. With climate change, that’s not true. As each year passes, we move past certain physical tipping points that make it impossible to recover large parts of the world that we have known.

Moyers: Just last week we got the National Climate Assessment Report, which says we’re now living in the warmest period in the history of modern civilization, and that the average global concentration of carbon dioxide has surged to the highest level in approximately 3 million years. Three million years!

McKibben: Three million years, and the last time there was this much CO2 in the atmosphere, the temperature of the planet settled several degrees higher, which results in approximately a 20-meter rise in the level of the oceans. Times Square is 16 meters above sea level, just to give you a little bit of reference. We’re playing with forces so enormous now...

As you know, I wrote the first book about climate change almost 30 years ago —

Moyers: 1989.

"End of Nature" by Bill McKibben

"The End of Nature" established McKibben as an environmental writer and he has written a dozen more books addressing climate change from many different angles...

McKibben: When I started writing about it, climate change was still theoretical and abstract. Now it bludgeons you weekly. Think about the last eight weeks and confine yourself to the small percent of the planet that’s covered by the United States. We had the greatest rainstorm in American history. Hurricane Harvey came ashore in your old state of Texas and dropped 54 inches in parts of Houston. That’s more rain than we’ve ever seen at one time in the United States. Hurricane Irma, on its heels, is the longest ever recorded on the planet—longest storm with a wind speed above 185 miles an hour. Maria comes to Puerto Rico 10 days after that, it knocks an entire island 30 years back in its development. It’s going to be that long before they get back to where they were in August. And then look at what happens in California after the hottest and driest summer ever recorded there. Napa and Sonoma, which are as close as you get to our definition of what constitutes the good life — you know, prosperous beautiful communities, surrounded by big buckets of wine — Napa and Sonoma burn in the course of hours. People flee for their lives...

Moyers: I don’t think any reader who knows you will put this book down without asking what does Bill McKibben think we can do now, given the folly of our government? What can we do about the fate of the Earth as the planet gets hotter and the United States turns thumbs down on responding. As you just said, you spent the last 30 years trying to warn us about the threat. You’ve written important books, you’ve produced stellar journalism, you’ve traveled and lectured, protested and petitioned. You’ve organized and led marches and got yourself arrested outside Barack Obama’s White House. Indeed, it wasn’t until things like that happened that Obama finally woke up and started coming up with policies to fight global warming. It took that long to move a progressive Democrat. Now we have have a president surrounded by like-minded cronies and supported by a Congress controlled by Republicans, a party that seems absolutely willing to let the Earth burn for profit. What would you have us do against such counter-resistance?

McKibben: We can’t make any progress in DC, at least for now. One of the things that we have to do in the moment is make a lot of progress in the places we can: in local communities, in states and cities where we have enough political purchase to get things done. And really that’s a larger span of places than you would think.

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○

The Question I Get Asked the Most

Via Green Builder

The questions come after talks, on twitter, in the days' incoming tide of email—sometimes even in old-fashioned letters that arrive in envelopes. The most common one by far is also the simplest: "What can I do?" I bet I've been asked it 10,000 times by now...

"What can I do to make a difference?"

It's the right question or almost: It implies an eagerness to act and action is what we need. But my answer to it has changed over the years, as the science of global warming has shifted. I find, in fact, that I'm now saying almost the opposite of what I said three decades ago.

Then — when I was 27 and writing the first book on climate change — I was fairly self-obsessed (perhaps age appropriately). And it looked like we had some time: No climate scientist in the late 1980s thought that by 2016 we'd already be seeing massive Arctic ice melt. So it made sense for everyone to think about the changes they could make in their own lives that, over time, would add up to significant change. In The End of Nature, I described how my wife and I had tried to "prune and snip our desires," how instead of taking long vacation trips by car we rode our bikes in the road, how we grew more of our own food, how we "tried not to think about how much we'd like a baby."

Some of these changes we've maintained — we still ride our bikes, and I haven't been on a vacation in a very long time. Some we modified—thank God we decided to have a child, who turned out to be the joy of our life. And some I've abandoned: I've spent much of the last decade in frenetic travel, much of it on airplanes. That's because, over time, it became clear to me that there's a problem with the question "What can I do."

The problem is the word "I." By ourselves, there's not much we can do. Yes, my roof is covered with solar panels and I drive a plug-in car that draws its power from those panels, and yes our hot water is heated by the sun, and yes we eat low on the food chain and close to home. I'm glad we do all those things, and I think everyone should do them, and I no longer try to fool myself that they will solve climate change.

Because the science has changed and with it our understanding of the necessary politics and economics of survival. Climate change is coming far faster than people anticipated even a couple of decades ago. 2016 is smashing the temperature records set in 2015 which smashed the records set in 2014; some of the world's largest physical features (giant coral reefs, vast river deltas) are starting to die off or disappear. Drought does damage daily; hundred-year floods come every other spring. In the last 18 months we've seen the highest wind speeds ever recorded in many of the world's ocean basins. In Basra Iraq — not far from the biblical Garden of Eden — the temperature hit 129 Fahrenheit this summer, the highest reliably recorded temperature ever and right at the limit of human tolerance. July and August were not just the hottest months ever recorded, they were, according to most climatologists, the hottest months in the entire history of human civilization. The most common phrase I hear from scientists is "faster than anticipated." Sometime in the last few years we left behind the Holocene, the 10,000 year period of benign climatic stability that marked the rise of human civilization. We're in something new now — something new and frightening.

Against all that, one's Prius is a gesture. A lovely gesture and one that everyone should emulate, but a gesture. Ditto riding the bike or eating vegan or whatever one's particular point of pride. North Americans are very used to thinking of themselves as individuals, but as individuals we are powerless to alter the trajectory of climate change in a meaningful manner. The five or ten percent of us who will be moved to really act (and that's all who ever act on any subject) can't cut the carbon in the atmosphere by more than five or ten percent by those actions.

The right question is "What can we do to make a difference?"

- ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○

Friend & Early Green Institute Adviser

○

Sept 2016 / Recalculating the Climate Math

Follow Bill on Twitter

- https://twitter.com/billmckibben

- https://twitter.com/hashtag/BillMcKibben?src=hash

- https://twitter.com/350

- https://twitter.com/hashtag/350org?src=hash

The Global Warming Reader, edited by Bill McKibben

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○

Bill McKibben

SJS / GreenPolicy360 Siterunner: On behalf of planet citizens within the global, open source Wiki networking community, GreenPolicy360 would like to take this time, following the historic next-step accomplishments of the 2015 Paris climate summit, to send multi-language "greening our blue planet" thanks to our former advisor, Bill McKibben.

Back when we, at Green Institute with our GreenPolicy project start-up, we approached Bill to join our advisor group and although he was deeply involved in his "Deep Economy" book and in initial phases of his own start-up project with the climate change/global warming movement group that became 350.org, he agreed to add his name to the Green Institute and share his thoughts as we conceived sharing "best green practices" via global online networking.

May 24, 2016, a moment's reflection on 350.org founder Bill McKibben

I personally want to thank Bill, a voice of our generation who feels deeply and acts with persistence and foresight to advance the critical, even life-enabling, work that all of us in the larger green, environmental movement are attempting. The climate change work is opening eyes now across the globe, in every country, every community.

Thank you Bill.

You are a true planet citizen.

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○

Wikipedia bio of Citizen McKibben

January 2016

William "Bill" McKibben

...In 2009, he led 350.org's organization of 5,200 simultaneous demonstrations in 181 countries. In 2010, McKibben and 350.org conceived the Global Work Party, which convened more than 7,000 events in 188 countries as he had told a large gathering at Warren Wilson College shortly before the event. In December 2010, 350.org coordinated a planet-scale art project, with many of the 20 works visible from satellites. In 2011 and 2012 he led the environmental campaign against the proposed Keystone XL pipeline project and spent three days in jail in Washington, D.C. It was one of the largest civil disobedience actions in America for decades. Two weeks later he was inducted into the literature section of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

He was awarded the Gandhi Peace Award in 2013. Foreign Policy magazine named him to its inaugural list of the 100 most important global thinkers in 2009 and MSN named him one of the dozen most influential men of 2009. In 2010, the Boston Globe called him "probably the nation's leading environmentalist and Time magazine book reviewer Bryan Walsh described him as "the world's best green journalist".

Early life

McKibben grew up in the Boston suburb of Lexington, Massachusetts, where he attended high school. His father, who was arrested in 1971 during a protest in support of Vietnam veterans against the war, had written for Business Week and was business editor at The Boston Globe in 1980. As a high school student McKibben wrote for the local paper and participated in statewide debate competitions. Entering Harvard University in 1978, he became editor of The Harvard Crimson. In 1980, following United States presidential election of Ronald Reagan, he determined to dedicate his life to the environmental cause.

Graduating in 1982, he worked for five years for The New Yorker as a staff writer writing much of the Talk of the Town column from 1982 to early 1987. He lived simply, sharing an apartment with David Edelstein, the film critic, and found solace in the Gospel of Matthew. He became an advocate of nonviolent resistance. While doing a story on the homeless he lived on the streets; there he met his wife, Sue Halpern, who was working as a homeless advocate. In 1987 he quit The New Yorker when its longtime editor William Shawn was forced out of his job, and soon moved to the Adirondack Mountains of upstate New York where he worked as a freelance writer.

Writing

McKibben began working as a freelance writer at about the same time that climate change appeared on the public agenda in 1988 after the hot summer and Yellowstone fires of 1988 and testimony by James Hansen before the United States Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources in June, 1988. Dr. Hansen of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration told a Congressional committee that it was 99 percent certain that the warming trend was not a natural variation but was caused by a buildup of carbon dioxide and other artificial gases in the atmosphere.

His first contribution to the debate was a brief list of literature on the subject and commentary published December, 1988 in The New York Review of Books and a question, "Is the World Getting Hotter?"

He is a frequent contributor to various publications including The New York Times; The Atlantic; Harper's; Orion magazine; Mother Jones (magazine); The American Prospect; The New York Review of Books; Granta; National Geographic (magazine); Rolling Stone, Adbusters, and Outside (magazine). He is also a board member at and contributor to Grist Magazine.

His first book, The End of Nature, was published in 1989 by Random House after being serialized in The New Yorker. Described by Ray Murphy of the Boston Globe as a "righteous jeremiad," the book excited much critical comment, pro and con; was for many people their first introduction to the question of climate change. "Gentle climate warrior turns up the heat", Toronto Star, 5 July 2015 and the inspiration for a great deal of writing and publishing by others. It has been printed in more than 20 languages. Several editions have come out in the United States, including an updated version published in 2006.

His next book, The Age of Missing Information, was published in 1992. It is an account of an experiment in which McKibben collected everything that came across the 100 channels of cable TV on the Fairfax, Virginia, system (at the time among the nation's largest) for a single day. He spent a year watching the 2,400 hours of videotape, and then compared it to a day spent on the mountaintop near his home. This book has been widely used in colleges and high schools and was reissued in a new edition in 2006.

Subsequent books include Hope, Human and Wild, about Curitiba, Brazil and Kerala, India, which he cites as examples of people living more lightly on the earth; The Comforting Whirlwind: God, Job, and the Scale of Creation, which is about the Book of Job and the environment; Maybe One, about human population; Long Distance: A Year of Living Strenuously, about a year spent training for endurance events at an elite level; and Enough, about what he sees as the existential dangers of genetic engineering and nanotechnology. Speaking about Long Distance at the Cambridge Forum, McKibben cited the work of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi and Csikszentmihalyi's idea of "Flow (psychology)" relative to feelings he, McKibben, had had — "taking a break from saving the world", he joked — as he immersed in cross-country skiing competitions.

Wandering Home' is about a long solo hiking trip from his current home in the mountains east of Lake Champlain in Ripton, Vermont, back to his longtime neighborhood of the Adirondacks. His book, Deep Economy: the Wealth of Communities and the Durable Future, published in March 2007, was a national bestseller. It addresses what the author sees as shortcomings of the growth economy and envisions a transition to more local-scale enterprise.

In the fall of 2007 he published, with the other members of his Step It Up team, Fight Global Warming Now, a handbook for activists trying to organize their local communities. In 2008 came The Bill McKibben Reader: Pieces from an Active Life, a collection of essays spanning his career. Also in 2008, the Library of America published "American Earth," an anthology of American environmental writing since Thoreau edited by McKibben.

In 2010 he published another national bestseller, Eaarth: Making a Life on a Tough New Planet--"Eaarth" is NOT a typo -- an account of the rapid onset of climate change. It was excerpted in Scientific American.

Some of his work has been extremely popular; an article in Rolling Stone in July 2012 received over 125,000 likes on Facebook, 14,000 tweets, and 5,000 comments - Global Warming's Terrifying New Math: Three simple numbers that add up to global catastrophe - and that make clear who the real enemy is

Environmental campaigns

Step It Up

Step It Up 2007 was a nationwide Environmentalism campaign started by McKibben to demand action on global warming by the U.S. Congress.

In late summer 2006 he helped lead a five-day walk across Vermont to call for action on global warming. Beginning in January 2007, he founded Step It Up 2007, which organized rallies in hundreds of American cities and towns on April 14, 2007 to demand that Congress enact curbs on carbon emissions by 80 percent by 2050. The campaign quickly won widespread support from a wide variety of environmental, student, and religious groups.

In August 2007 McKibben announced Step It Up 2, to take place November 3, 2007. In addition to the 80% by 2050 slogan from the first campaign, the second adds "10% reduction of emissions in three years ("Hit the Ground Running"), a moratorium on new coal-fired power plants, and a Green Jobs Corps to help fix homes and businesses so those targets can be met" (called "Green Jobs Now, and No New Coal").

350.org -- https://www.greenpolicy360.net/w/350.org

In the wake of Step It Up's achievements, the same team announced a new campaign in March 2008 called 350.org. The organizing effort, aimed at the entire globe, drew its name from climate scientist James E. Hansen's contention earlier that winter that any atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide (CO2) above 350 parts per million was unsafe. "If humanity wishes to preserve a planet similar to that on which civilization developed and to which life on Earth is adapted, paleoclimate evidence and ongoing climate change suggest that CO2 will need to be reduced from its current 385 ppm to at most 350 ppm, but likely less than that." Hansen et al. stated in the Abstract to their paper. Hansen, J., Mki. Sato, P. Kharecha, D. Beerling, R. Berner, V. Masson-Delmotte, M. Pagani, M. Raymo, D.L. Royer, and J.C. Zachos, 2008: Target atmospheric CO2: Where should humanity aim? Open Atmospheric Science Journal, 2, 217-231

350.org, which has offices and organizers in North America, Europe, Asia, Africa and South America, attempted to spread that 350 number in advance of international climate meetings in December 2009 in Copenhagen. It was widely covered in the media. On Oct. 24, 2009, it coordinated more than 5,200 demonstrations in 181 countries, and was widely lauded for its creative use of internet tools, with the website Critical Mass declaring that it was "one of the strongest examples of social media optimization the world has ever seen." Foreign Policy magazine called it "the largest ever global coordinated rally of any kind."

Subsequently the organization continued its work, with the Global Work Party on 10/10/10 (10 October 2010).

Keystone XL

McKibben is the lead environmentalist against the proposed Canadian-U.S. Keystone XL pipeline project.

People's Climate March

On May 21, 2014, McKibben published an article on the website of Rolling Stone magazine (later appearing in the magazine's print issue of June 5), titled "A Call to Arms", which invited readers to a major climate march (later dubbed the People's Climate March in New York City on the weekend of September 20–21. Both dates were mentioned in the article because the actual date of the march was uncertain at the time of publication. After negotiations with New York City authorities, event planners chose Sunday, September 21 as the date. In the article, McKibben calls climate change "the biggest crisis our civilization has ever faced", and predicts that the march will be "the largest demonstration yet of human resolve in the face of climate change".

○ ○ ○ ○ ○

Awards

McKibben has been awarded both a Guggenheim Fellowship (1993) and a Lyndhurst Fellowship. He won a Lannan Literary Award for Nonfiction in 2000. In 2010, Utne Reader magazine listed McKibben as one of the "25 Visionaries Who Are Changing Your World." He has honorary degrees from Whittier College, Marlboro College, Colgate University, the State University of New York, Sterling College (Vermont), Green Mountain College, Unity College (Maine), and Lebanon Valley College. In 2010 he won the Puffin/Nation Prize for Creative Citizenship for his work with 350.org. In 2013, he won the international environment and development prize. In 2014, he and 350.org were awarded the Right Livelihood Award"...for mobilising growing popular support in the USA and around the world for strong action to counter the threat of global climate change".

Personal life

McKibben resides in Ripton, Vermont with his wife, writer Sue Halpern. Their only child, a daughter named Sophie, was born in 1993 in Glens Falls, New York. He is a Schumann Distinguished Scholar at Middlebury College, where he also directs the Middlebury Fellowships in Environmental Journalism. McKibben is also a fellow at the Post Carbon Institute. McKibben is a long-time Methodist.

Books

- The End of Nature (1989) ISBN 0-385-41604-0

- The Age of Missing Information (1992) ISBN 0-394-58933-5

- Hope, Human and Wild: True Stories of Living Lightly on the Earth (1995) ISBN 0-316-56064-2

- Maybe One: A Personal and Environmental Argument for Single Child Families (1998) ISBN 0-684-85281-0

- Hundred Dollar Holiday (1998) ISBN 0-684-85595-X

- Long Distance: Testing the Limits of Body and Spirit in a Year of Living Strenuously (2001) ISBN 0-452-28270-5

- Enough: Staying Human in an Engineered Age (2003) ISBN 0-8050-7096-6

- Wandering Home (2005) ISBN 0-609-61073-2

- The Comforting Whirlwind : God, Job, and the Scale of Creation (2005) ISBN 1-56101-234-3

- Deep Economy: The Wealth of Communities and the Durable Future (2007) ISBN 0-8050-7626-3

- Fight Global Warming Now: The Handbook for Taking Action in Your Community (2007)

- The Bill McKibben Reader: Pieces from an Active Life (2008) ISBN 9780805076271

- American Earth: Environmental Writing Since Thoreau (edited) (2008) ISBN 9781598530209

- Eaarth: Making a Life on a Tough New Planet (2010) ISBN 978-0-8050-9056-7

- The Global Warming Reader (2011) ISBN 978-1-935928-36-2

- Oil and Honey: The Education of an Unlikely Activist (Times Books, 2013) ISBN 9780805092844

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○

External links

Review of Eaarth: Making a Life on a Tough New Planet

@Amazon/Comments on Deep Economy

Keystone: How Bill McKibben Turned a Pipeline into an Environmental Rallying Point

Bill McKibben's Battle Against the Keystone XL Pipeline

○

Climate Work activities

Organize a street party in your neighborhood and invite experts to teach your community about ways on how you can decrease a household’s carbon footprint.

Here is a list of suggested workshops and tips on organizing one:

Workshop on how families can maximize the potential electricity savings at home. From smart power use, avoiding energy waste and structural or design changes. Ask your guests to share what they’ve done at home.

Workshop on bicycle safety and maintenance. Get your local bicycle shop to co-host the event by providing a mechanic or ask avid-cyclists in your neighborhood if they’re interested to be one.

Workshop on growing your own food and making organic compost. Invite your local garden center to talk about which plants are suitable to your area’s weather and endemic to the place.

2 Get your community to switch to green energy

Sometimes, it’s just a matter of letting people know that they have a choice! Some tips in getting your community to switch:

Research all the renewable energy providers in your area and make a leaflet about it. Include advice on smart energy usage.

It’s time to chat with your neighbor! Knock on their doors; having a face-to-face conversation is a great way for people to take on your challenge.

If the energy providers in your area don’t offer green energy – start a petition to get your community to demand them to do so.

3 Veggie dinner or picnic

Organize a dinner or picnic with friends and family and serve only yummy vegetarian food. By the end of the dinner, get them to commit to go meat-free at least 1 day a week.

Remember to opt for local and organic ingredients

4 Mass Bike Riding

Gather hundreds of friends and friends of friends for a mass bike ride to show how a car-free community could look like. If your area doesn’t have the proper infrastructure to make cycling safe and convenient, get your school or office to install bike racks. Also ask your local government to designate more bike lanes in your community.

5 Deliver a message about dirty fuels to your local government

If you have a local dirty power plant, take some photos of the facility and deliver them to your local government. Tell your leader about the risks this power plant represents to the community and to the planet. Remind them that what your community need is an Energy [R]evolution.

6 Tell our leaders to “get to work” for you, not dirty energy companies

Research how much money your local representative have received from dirty energy companies. Deliver giant price tags or checks to politicians that say how much dirty energy money they’ve received. Remind them that what their voters want is an Energy [R]evolution.

7 Organize a party demonstrating energy solutions to show your leaders that you want an Energy [R]evolution in your community. Some of the things you can do are:

Gather lots of people and go to a dirty energy facility near your home Hold mini wind turbines to show the contrast between clean and dirty energy. Set up an exhibit area featuring solar-powered lamps, solar cookers, solar-powered charging stations for laptops and mobile phone.

8 Put Solar On It

Ask by letter, phone, email or personally your local politician whether they will install solar energy and/or hot water systems on their roof on the Energy [R]evolution work party. If they agree, great! If they don’t, you could pool community money to buy them one, and deliver it to the office. Ask them to pay the tab after they accept it!

9 Plant a tree in front of a dirty energy power plant or at the site of a proposed plant.

Better yet, gather 100 people and plant 100 trees or a thousand! Do your homework first to make sure you find a spot where you can do this legally. Your local garden center might be able to donate some trees and teach you the best way to plant them. Check out the status of the trees after you’ve planted it.

10 Conduct an energy audit at your local government representative’s office and get them to support an Energy [R]evolution.

Get them to choose a green energy provider to power the building or implementing smart ways on reducing greenhouse gas emissions, or commit to a renewable energy source for your community instead of hosting dirty energy such as coal, oil or nuclear power.

○

○

- Anthropocene

- Atmospheric Science

- Bioneers

- Citizen Science

- Climate Change

- Climate Policy

- Democracy

- Desertification

- Divestment from Fossil Fuels

- Earth Observations

- Earth360

- Earth Imaging

- Earth Science from Space

- Earth Science

- Earth System Science

- Ecology Studies

- Environmental Protection

- Environmental Security

- Extinction

- Global Warming