User talk:Siterunner

<addthis />

Steven J Schmidt | SJS | Siterunner-Founder - GreenPolicy360

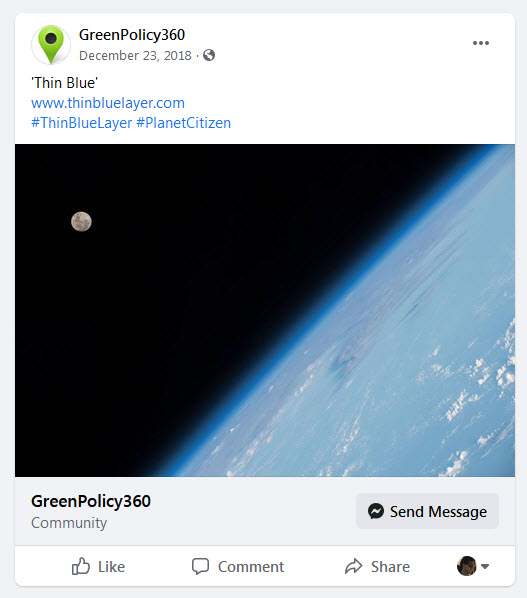

"The mission of GreenPolicy360 is found in protecting life, the Commons, our home."

-- Steven Schmidt

Email: [email protected]

About GreenPolicy360 | "Greening Our Blue Planet"

··············································

2006, Clearwater, Florida

Steven J. Schmidt (SJS)

Email: [email protected]

Personal Contact: [email protected]

·······································································

A Whole Earth Point of View -- http://www.greenpolicy360.net/w/Category:Whole_Earth

- Steven Schmidt, GreenPolicy360 Siterunner....

- DYK? Yes, we know, we remember the beginnings !

- 'Earthrise' and 'Earth Day'

Beginnings of the Modern Environmental Movement

* https://www.greenpolicy360.net/mw/images/1969_beginnings_of_the_modern_environmental_movement.pdf

🌎

On the 50th Anniversary

Memories on the Road to the First Earth Day

By Steve Schmidt

·········································

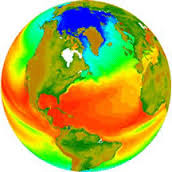

SJS/GreenPolicy360: "We are the first generation to scientifically and systemically monitor the 'Vital Signs' of the Earth...

Let us work now to expand our vision and act to protect Earth's living systems. The well-being of future generations is in our hands."

Planet Citizens, Planet Scientists

SJS/GreenPolicy360 Siterunner: The beginnings of modern environmental and climate science can be traced to the 1960s and 1970s.

The U.S. National Academy of Sciences played a key role in laying a foundation of scientific reports and data.

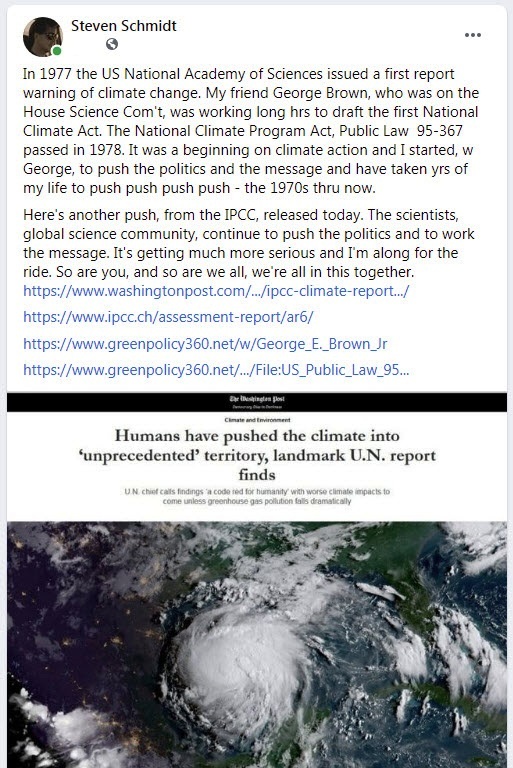

SJS/Memories of the first Climate Act legislation (Drafted by Rep. George E. Brown) 1978

············································································

Climate Problems, Climate Solutions

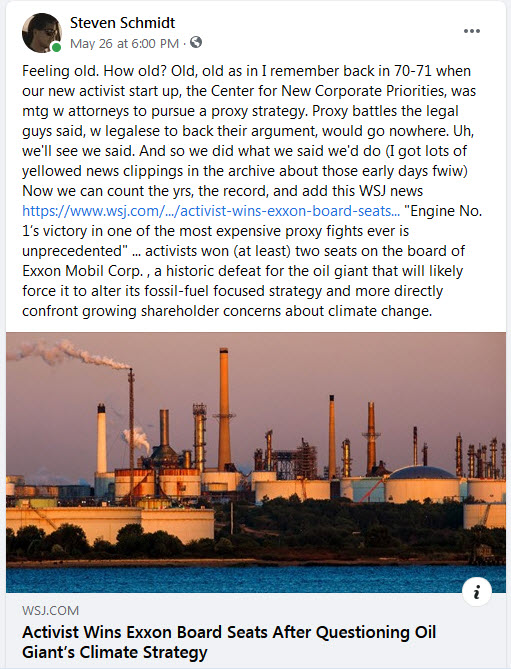

- Post to Facebook | Aug. 9, 2021

- Beginnings of a new vision, life affirming, 'Earthrise' https://www.greenpolicy360.net/w/File:Above.png

Sept. 26, 2021

Planet Citizens, Planet Scientists, Preserving & Protecting the Home Planet Earth

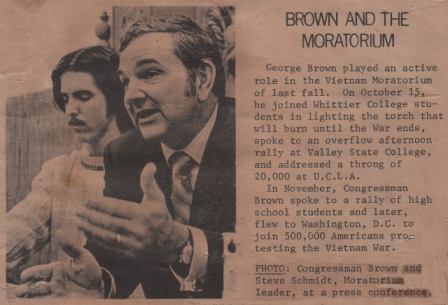

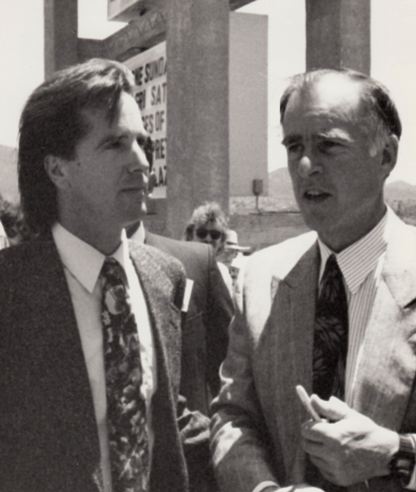

GreenPolicy360: The original Mission Statement of the newly launched U.S. space program spoke of our planet and our responsibilities. GreenPolicy360's founder was fortunate, beginning in the 1960s, to listen to Congressman Brown Congressman George E. Brown point to the NASA plan and explain how he saw Congress put into action the reality of a multi-year, coordinated, multi-agency program to achieve mission goals.

Earth science, measuring and monitoring Earth's life-enabling systems was given highest priority. Landsat's program was set in motion as a decades long, first-ever digital scanning remote satellites data collecting study. An array of satellites began to launch, creating and combining the expanding resources of NASA, USGS, NOAA, and an array of educational and scientific institutions and aeronautics business.

The overall goal, Representative Brown continually explained in his Congressional Science, Space & Technology leadership roles over the decades, was to 'understand, preserve and protect our planet' as we, humanity, developed first-generation Earth Science and looked beyond Planet Earth to study 'the heavens'.

George, as a senior member and as a chair of oversight committees, knew that we needed to speed up the science on environmental protection, climate, 'measuring and monitoring' and NASA-NOAA-JPL and all the research/data/missions became his legacy. The NASA Earth Observing System and open access to the scientific data, across scientific endeavors globally, is my friend George today still here in action....

Here's to George E. Brown Jr who led Earth Science initiatives and environmental law action in the U.S. Congress for three decades. Here's to the many visionaries, thinkers and doers who have carried on preserving and protecting our home planet.

(SJS, 2022)

* https://www.greenpolicy360.net/w/File:Earth_System_Observatory.jpg

* https://www.greenpolicy360.net/w/File:Earth_Information_Center_-_2022_Graphic_NASA.png

Steve Schmidt & Congressman George Brown

"My friend George" -- a Mentor & a Colleague over Decades of Earth Science Action

- 🌎

- Eco-nomics

- Beyond GDP... GDP+

- https://www.greenpolicy360.net/w/Eco-nomics

- https://www.greenpolicy360.net/w/Category:Eco-nomics

- https://www.greenpolicy360.net/w/Category:Ecological_Economics

- https://www.greenpolicy360.net/w/Category:Externalities

- http://www.greenpolicy360.net/w/Environmental_full-cost_accounting

- LA Smog in the 1950s/60s, described as worst in the world, the 'smog' motivated first-ever Calif. clean air initiatives

- (see GreenPolicy360's story of Congressman George Brown's EPA/Clean Air Act work)

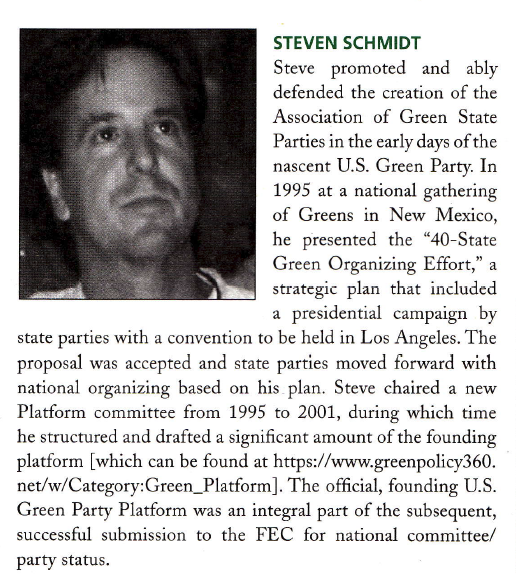

- Green Horizon Magazine speaks of Steve Schmidt as a Founder of the US Green Party

Steve Schmidt: "In drafting the founding Green Party platform, I was attempting to put forward a 'politics of values, an expansion of a rights agenda'. The goal was a 'serious, credible, platform-based politics'. The Green Party has expanded internationally to become a worldwide green political force in over 100 countries. We are an 'out in front' politics..."

- Hannah Arendt, Professor at the Graduate Faculty of the NYC New School

- Inspirational during SJS's graduate work at the New School

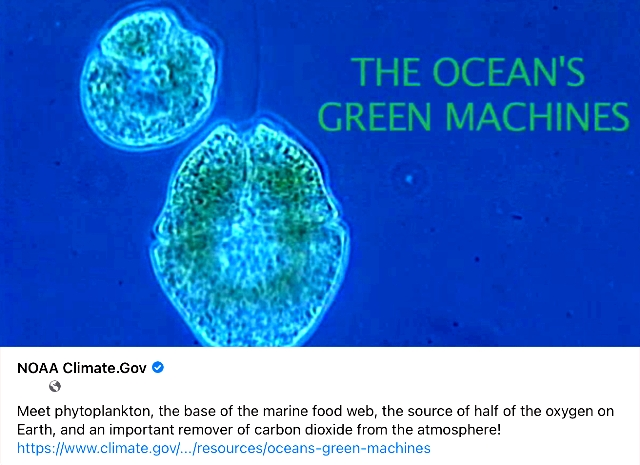

Source of atmospheric oxygen, Phytoplankton

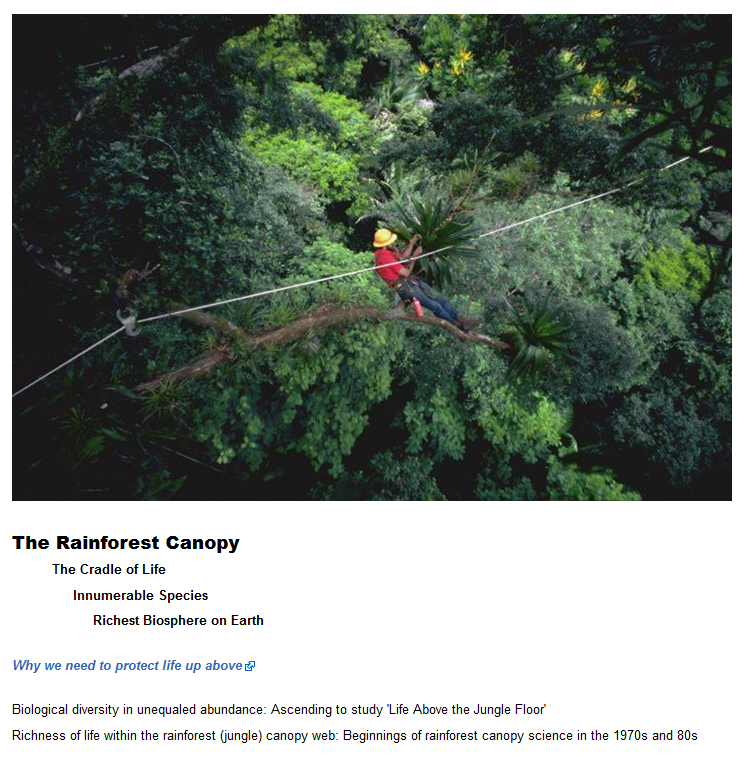

Source of atmospheric oxygen, Photosynthesis of the Forests

- Bioneering Science: A "Jacques Cousteau of the Rainforest Canopy"

- ··············································································

- Protect Life on Earth Before It's Too Late

GreenPolicy360: In 1994, your Green Policy siterunner ran for Lieutenant Governor in New Mexico on a "Children's Agenda". After the election, an appointment by the elected Governor, hearings and confirmation vote by the NM Senate, I moved into a constitutional position on the State Board of Education 'overseeing public education, policy and management' of some 50% of the state's budget.

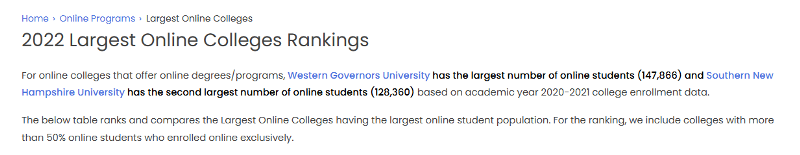

My first act in 1995 as a member of the Board was to propose a "K-16" strategic plan and expand access to the Internet to all schools in NM. One of the tasks I took on was chairing NM Technology initiatives, including representing the state and serving on the start up Working Group for a new multi-state 'virtual university'. Online, distance learning has taken many steps forward since then. Over the years, the 'virtual' Western Governors University has grown to be a powerful force in education. Here is a touch of the wisdom and skills imparted via the WGU:

- Launching a Forward-looking Online University / (1995-96)

GreenPolicy360 and Strategic Demands

GreenPolicy360's origins connect deeply with Strategic Demands. The intersection began in the 1960s, with a new Congressman, George E. Brown from East Los Angeles and a young debater, a high school student who set in motion with the Congressman a multi-year journey to develop climate/environmental science and generational activism and strong, deep opposition to nuclear weapons.

Here is a quick snapshot of where our connections and work have led and links you can follow with our group of founders.... relationships and ideas carried forward from the 1960s and 70s and going strongly today.

We are diverse mix, across the globe now with the Internet, many voices, colors, ages, especially young people joining in. GreenPolicy360 and Strategic Demands.... including Steve Schmidt, George E. Brown, Dan Ellsberg, Jerry Brown, Roger Morris, and Charlene Spretnak.

Welcome along... green, environmental, national and global.... strongly confronting and working to solve our generation's existential challenges. Reaching across our home planet, touching and interacting with planet citizens, looking to share solutions to the pressing problems and challenges of our generation.

Links to voices of StratDem/GreenPolicy360 include --

Steve Schmidt

- https://www.greenpolicy360.net/w/User:Siterunner

- https://www.greenpolicy360.net/w/Out_in_Front

- https://www.greenpolicy360.net/w/Earth_Day_Memories_on_the_50th_Anniversary

- https://www.greenpolicy360.net/w/Strategic_Policy-Internet_Online_Rights

- https://strategicdemands.com/?s=steve+schmidt

- https://strategicdemands.com/?s=editor

George E. Brown

- https://www.greenpolicy360.net/w/George_E._Brown_Jr

- https://www.greenpolicy360.net/w/File:US_Role_George_E_Brown_2.pdf

- https://www.greenpolicy360.net/w/File:US_Role_George_E_Brown_3.pdf

- https://strategicdemands.com/?s=george+e+brown

Roger Morris

- https://www.greenpolicy360.net/w/Roger_Morris_Bio

- https://www.greenpolicy360.net/w/Green_Institute

- https://strategicdemands.com/?s=roger+morris

Roger Morris, former National Security Council, and Steve Schmidt, GreenPolicy360 founder, write about Strategic Demands for New Definitions of National Security.

"As nations across the planet confront an array of unprecedented existential threats, GreenPolicy360 & Strategic Demands look to the bigger picture, realistic politics, and national defense with new definitions of national & global security. "

Read the Associated Press story:

File:Surviving Victory WashingtonDC conf 09 12 06.pdf

- More from Strategic Demands and GreenPolicy360:

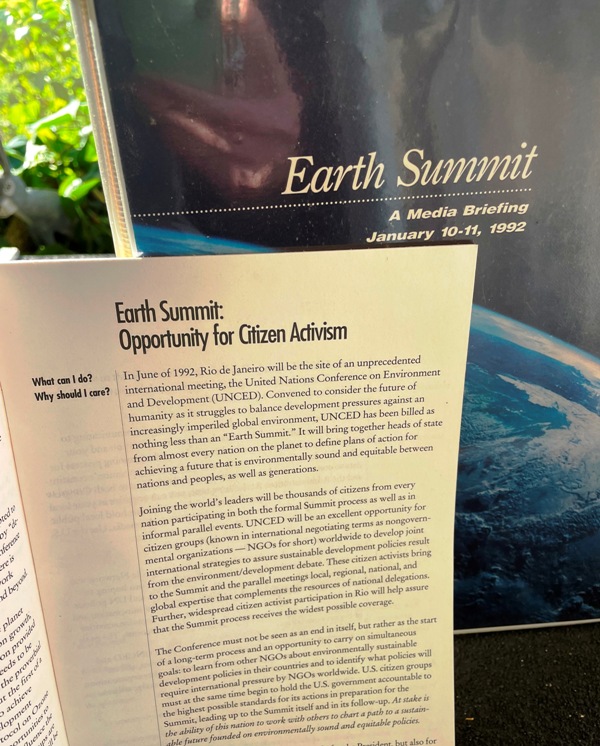

1992 Presidential Campaign

Governor Edmund (Jerry) Brown Brings Forward a Diverse Eco-nomic/Environmental Platform

SJS / Advancing a presidential campaign, your GreenPolicy360 siterunner worked with the Governor to draft the 'we the people' campaign platform, taking new ideas into the U.S. presidential debate to press the Democratic Party into a progressive direction...

- At the Democratic Party Platform Hearings

- Governor Jerry Brown

🌎

Green Politics, Independent Politics

"Spoiling for a Fight: Third-Party Politics in America"

- Written by Micah Sifry

Paperback: 384 pages

Publishers: Routledge; April 2003, ISBN-10: 0415931436

Taylor and Francis; January 2013, Kindle Edition, ISBN-13: 978-0415931434

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○

From the Introduction

More Americans now identify as political independents than as either Democrats or Republicans. Tired of the two-party gridlock, the pandering, and the lack of vision, they've turned in increasing numbers to independent and third-party candidates... Third-party activists are true believers in democracy, and if America's closed two-party system is ever to be reformed, it will be thanks to their efforts.

Excerpts:

P.46

Over the last ten years, I have met and interviewed many third-party activists. Some, like Steve Schmidt of the New Mexico Green Party, have traveled fairly straightforward journeys from the liberal-left wing of the Democratic Party out to the further left of the Greens. Before becoming a Green in 1994, Schmidt worked for Democratic presidential candidates Michael Dukakis in 1988 and Jerry Brown in 1992.

As a co-drafter of Brown’s “Take Back America” platform, Schmidt accompanied Brown to the Democratic platform hearings, and it is there that he experienced his personal epiphany. “There I had Ron Brown [then the Democratic national chairman] tell me ‘get lost’ that what we were urging was not in the cards, that increased fund-raising was, there would be no “unilateral disarmament” and so on,” he recalled. “There are a lot of stories here but the bottom line is that the Democratic leadership moved to get back the ‘Reagan Democrats’ and re-align itself with business interests.” Schmidt wanted no part of such a right-leaning Democratic Party, so he left.

The 1992 Presidential Platform brought to the Democratic Party Platform meeting

P. 153

The New Mexico Greens’ breakthrough came in 1994, with Roberto Mondragon’s run for governor. Until then, the Greens had essentially been invisible to mainstream public consciousness.

...the New York Times published a lengthy story titled “Rebellion of Greens Is Brewing in the West.” Mondragon, a fifty-four-year-old former Democratic lieutenant governor who was also a Spanish-language radio broadcaster, had been first elected to the state legislature at the age of twenty-five. Now, after a failed run for Congress in 1982, he had decided to reenter politics as a Green, dispelling the image of the Greens as total amateurs. Not only that, he was a Hispanic native of the state, bringing high-level diversity to a movement that was primarily led by well-educated whites. Challenging Governor Bruce King, a wealthy, conservative, seventy-year-old Democrat close to the state’s business elite of ranchers and oilmen, and Gary Johnson, an energetic Republican newcomer who was also a millionaire, Mondragon had a strong appeal to many of the state’s Hispanics and other moderate-income voters. A modest man with a grizzled face and a white beard, he was a well-known and much-liked local personality who had a small part in Robert Redford’s movie The Milagro Beanfield War, a story dear to his heart for its advocacy of the common people against the state’s big landowners and resource hogs. He and Steve Schmidt, candidate for lieutenant governor, ran on a platform fashioned by Schmidt that melded environmental and economic concerns (“ We absolutely refuse to cater to holier-than-thou Range Rover environmentalists,” Schmidt said), and blended in issues of high concern to Perot voters, including term limits, campaign finance reform, and deficit reduction.

At its core, the Mondragon-Schmidt Green platform upheld the populist traditions of the Democratic Party— calling for universal health care coverage, a “living wage” instead of a minimum wage, deep cuts in military spending and corporate welfare, and increased spending on public schools. But it was far from a doctrinaire “left” document, including explicit support for small business and property tax reform rather than pie-in-the-sky proclamations of nationalizing industries or abolishing the military. Significantly, Mondragon and Schmidt weren’t running alone, but as part of a slate of candidates vying for a wide range of state and local offices. And while Republicans triumphed across the country in 1994, gaining a majority of the U.S. House for the first time in many years, the New Mexico Greens demonstrated there was substantial public support for a new politics in their state. Their candidate for state treasurer, Lorenzo Garcia, a Vietnam veteran and federal bank examiner, got 33 percent of the vote. Fran Gallegos, another veteran and former Republican with innovative ideas about alternatives to incarceration, got 43 percent in her bid to become a Santa Fe municipal judge (setting up her eventual victory two years later). And Mondragon and Schmidt got 10 percent statewide, despite having raised just $ 100,000. Most promising, they won the vote among eighteen- to twenty-nine-year olds. (Schmidt was also appointed to a seat on the state board of education as a result.) Suddenly, the Greens were on the map.

P.155

Bill Clinton’s election in 1992 was also a resounding victory for conservatives in the Democratic Party, who blamed party liberals for the losses of George McGovern, Walter Mondale, and Michael Dukakis. Clinton, a southern governor who catered carefully to his state’s business establishment after one unsuccessful term in office as a semi-liberal, had been one of the founders of the Democratic Leadership Council, an elite body that looked to corporate America for support and pushed the party to the right on issues like crime, welfare, and foreign policy. During the primaries, his leading opponent was former California governor Jerry Brown, who ran a progressive campaign focused on political reform, universal health care, respect for human rights, and radical tax reform.

One of the authors of Brown’s “Take Back America” platform was none other than Steve Schmidt, who had earlier worked on Michael Dukakis’s 1988 run. Unlike past years, when losing candidates for the Democratic nomination were allowed to speak to the national convention and make their dissenting views into a “minority report” to the party’s platform, in 1992 no such accommodation was made for Brown and his supporters. Schmidt recalls that the turning point came when the party’s platform committee came to Santa Fe to hold a regional hearing.

“Our issues had taken us from dark horse to second place in the primaries. So Jerry [Brown] asked me to meet with Ron Brown [the Democratic national chair], to put forward our proposal that electoral reform and campaign finance reform be the focus of the first 100 days of the Clinton administration. Start by pushing money back from the trough that was corrupting Washington, and then go with health care reform. And Ron Brown said, ‘Get lost.’”

In Schmidt’s view, that was the moment that many progressives stepped away from the Democratic Party. Among the people listening during the platform committee’s hearing was Roberto Mondragon, who had supported Democratic liberals like Robert Kennedy, George McGovern, and Ted Kennedy, and had last been involved in party politics supporting Jesse Jackson’s presidential bids in 1984 and 1988. Afterward, Schmidt recalled, “Roberto came to me and said he’d run with me if I’d run with him.” At the urging of Abraham Gutmann and other Greens, Schmidt soon decided to switch parties and bring the “Take Back America” platform that he had helped craft for Jerry Brown and turn it into the New Mexico Greens’ platform. Gutmann was also working on converting Mondragon, who later said he was impressed with the party’s positions. “The Green Party stands for what the state Democratic Party ought to stand for,” he told the New York Times. Voicing his outrage at how the party who had nurtured him had changed, he added, “There used to be room for liberals in the Democratic Party here. But there isn’t room anymore. If you look at the contributors for the Democratic Party today, it’s the same people that you’ll find on the list of contributors for the Republican Party.” (Mondragon’s last bid for public office had been in 1982, when he faced Democrat Bill Richardson in a contest for the First Congressional District seat; Richardson’s war chest of $ 400,000 was ten times what Mondragon could raise.) Ultimately, Mondragon’s decision to switch parties was triggered by the results of the 1994 Democratic primary in New Mexico, in which the incumbent governor, King, defeated his lieutenant governor, Casey Luna, thanks to the late entry of Jim Baca, an environmentalist who had just been fired from his position as head of the federal Bureau of Land Management. Baca split the anti-King vote with Luna, enabling King to win with a bare plurality. Luna, in Mondragon’s view, “would have been a move away from the good ‘ol boy system,” while Governor King just represented the interests of ranchers, including his own King Brothers Ranch. 25 According to Mondragon’s campaign treasurer, Norm Shatkin, “Middle-class Hispanics were outraged over Casey Luna’s defeat. They felt that King had stolen the primary by inducing Jim Baca to run, thereby taking away enough votes from Luna to give King a plurality.”

P.167

All of these contests produced much tension between Greens and local Democrats angry at losses to Republicans. Greens had two responses. First, that Democrats should stop taking progressives for granted and pay more attention to their concerns. Second, that Democrats should support the enactment of instant-runoff voting to end the problem of vote splitting. Under such a system, voters would indicate their first, second, third, and so on choices on the ballot, and those whose candidate got the least number of first choices would have their votes transferred to their second choice, until one candidate achieved a majority. As a result of the Green challenge, New Mexico has become one of a handful of states where such legislation has shown real prospects (the others are Alaska, where the “Republican Moderate” party has siphoned votes from the Republicans at the same time that Greens have threatened Democrats; Vermont, where the Progressive Party has a solid presence and a third of the state Senate has cosponsored a bill; and Washington state).

P. 173

It’s tempting to say that New Mexico is a special case— full of newcomers in search of new politics, exceptionally poor, a small state with relatively easy access to the ballot and the media, where the Democrats have been particularly inept and the Greens have been blessed with a critical mass of gifted organizers. I’m more inclined to say that the New Mexico Greens’ organizing model is worth emulating— build a local foundation through electoral work connected to community-based issue activism; choose selected higher-level races to run in, preferably where the party already has a base; push for electoral reforms to allow people to vote for the best candidate and not the “least worst”; use the power to “spoil” very carefully, not indiscriminately, and highlight the party’s ten key values— especially if organizers can involve more people of color and working-class people from the start. Such a model may well be exportable to other states. It was with such a goal in mind that a small group led by New Mexican Steve Schmidt and Californians Greg Jan and Mike Feinstein (a Green member of the Santa Monica city council), set out in late 1994 with a proposal for a “40 State Green Organizing Effort.”

In Schmidt’s words, “The ‘serious, credible, platform-baseď model we had been using became the basis for a national organizing effort.” The next summer the New Mexico Green Party, led by Cris Moore, invited Greens from around the country for a national gathering that brought together activists from all wings of the movement. At this event, Schmidt and the others laid out their argument that the time was ripe for the Greens to run a presidential campaign that would foster the development of Green state parties in the same way that high-level state races could nurture local Green organizing. “On the ‘short list’ of candidates we presented— accompanying a national survey of Greens expressing broad support for a presidential campaign that would build the Green Party— were the names of [farmworkers organizer] Delores Huerta, [Texas populist] Jim Hightower and Ralph Nader,” Schmidt recalled. One candidate— Nader— was open to a possible run. In the fall of 1995 he made that interest concrete by allowing the Greens to put his name on their ballot line in California. A new experiment in third-party politics was under way.

P. 176

By the time the 1996 election rolled around, Nader was ready to experiment with a slightly bigger lever. Angered by many of President Clinton’s rightward moves— the push to pass the North American Free Trade Agreement and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, the sellout to corporate managed care instead of universal health care, and finally a decision to rescind the federal highway speed limit— Nader agreed to a request from Greens Steve Schmidt, Mike Feinstein, and Greg Jan along with other progressive activists1 to put his name on the California Greens March 1996 primary ballot for president. Ultimately he got on the ballot in twenty-one states, plus the District of Columbia.

¤

[In 2000, at the national Green Party convention, Renaissance Hotel in Colorado, Nader accepted the nomination and addressed the delegates and several thousand in attendance]

“The Green Party stands for a nation and a world that consciously advances the practice of deep democracy,” Nader said. He went on: A deep democracy facilitates people’s best efforts to achieve social justice, a sustainable and bountiful environment and an end to systemic bigotry and discrimination against law-abiding people merely because they are different. Green goals place community and self-reliance over dependency on ever larger absentee corporations and their media, their technology, their capital, and their politicians. Green goals aim at preserving the commonwealth of assets that the people of the United States already own so that the people, not big business, control what they own, and using these vast resources of the public lands, the public airwaves and trillions of worker pension dollars to achieve healthier environments, healthier communities and healthier people.”

The Green Party founding platform, 2000

P. 199

Just as the media and Nader himself were raising the bar at the Greens national convention in Denver in June 2000, the Democrats and Al Gore took their first moves to lower the boom on the troublesome maverick. For the most part, Gore’s supporters had said little about him through much of the spring, with the exception of liberal Massachusetts congressman Barney Frank, who set to work early at corralling progressives for the vice president. But as the polls showed Nader on the rise, the Gore team responded with a two-pronged strategy reminiscent of their treatment of Perot in l993. First, Gore tacked left. For example, on the same day of Nader’s acceptance speech in Denver, the Gore campaign went after “Big Oil,” promising to go after its “stranglehold” on the economy by promoting more clean energy sources and greater efficiency. Sounding like a Nader acolyte, Gore spokesman Chris Lehane said, “The entrenched interests want to protect the status quo, and the apologists for these interests say that we simply cannot have a clean environment and affordable energy at the same time. They say we can’t do this. Al Gore says we can.”

A few days later, Gore expanded his neopopulist rhetoric to take on the big pharmaceutical companies as well. His new line, repeated again and again in stump speeches, was “The question is whether you’re for the people or for the powerful.” Enlarging this theme, he went after the Republican Congress for blocking needed reforms like prescription drug benefits or a patients’ bill of rights at the behest of wealthy special interests, and said those same interests were bankrolling George Bush’s campaign. Republican commentator William Kristol observed, “Ralph Nader may well have made Al Gore a better presidential candidate. He has forced Al Gore to be more populist.” Kristol added, “The response to Nader has energized the Gore camp. The last ten days have been the first time since the primaries that you watch the evening news and think, ‘Hey, Gore is on the offensive.’” Indeed, Gore’s poll numbers rose each time he turned on the “populist” juice. His problem was that, thanks to his own conservatism and his need to succor his financial sponsors, he always pulled back and avoided talking about any kind of systemic changes.

P. 201

... the presidential debates [were] the last choke point protecting the two-party duopoly from serious competition. In January, the Commission on Presidential Debates— a private body set up and controlled by the two major parties— decided that a candidate had to have at least an average of 15 percent support across five national polls in late September in order to be invited to participate. The commission claimed this standard would ensure that the public would hear only from those candidates with a serious chance of winning the presidency, but this was a transparently silly excuse. For one, it was not impossible with a candidate with a lower standing in the polls to win: Ventura was hovering around 10 percent when he joined Skip Humphrey and Norm Coleman in their debates, and in 1992 Russ Feingold— the eventual senator from Wisconsin— won a three-way primary three weeks after polling at just 10 percent. The debate commission had perpetrated, as the League of Women Voters had warned when it disassociated itself from the commission in 1988, “a fraud on the American voter.” If 15 percent had been the threshold, Jesse Ventura, Ross Perot, and John Anderson would have all been excluded from debates that they participated in the years they ran for high office. Besides, if having a serious chance to win the presidency was the most important criterion, why did the commission invite Bob Dole in 1996, even though he had never led in the polls and most knowledgeable observers wrote off his chances? The claim that having more than two candidates would confuse voters was also ridiculous. The public had tolerated — nay, it had enjoyed — the participation of a half-dozen or more candidates in the Republican presidential primaries of 1999– 2000, as well as similar encounters of Republicans and Democrats in 1996 and 1992. More voices meant more views and, ultimately, greater voter participation. Jamin Raskin, a professor at American University and the lawyer who led Perot’s 1996 and Nader’s 2000 legal challenges to the commission’s authority, put his finger on the problem. “The question the commission uses to determine who debates shouldn’t be ‘Who do you plan to vote for?"

The question should be, ‘Who would you like to see in the debates?’” In fact, more than half the public supported Nader’s (and Buchanan’s) inclusion in the debates. As Raskin wrote in a seminal essay he titled “The Debate Gerrymander,” “The whole point of a political campaign period is to allow candidates— through popular appeals, organizing and debates— to change public opinion.” Control over access to the debates really was a form of mass mind control. But these arguments had no impact on the commission, which had never really had an open mind about the issue.

¤

Al Gore lost the 2000 election for a lot of reasons. Some were political. He was hurt by his long association with President Clinton. There were too many versions of Gore — the man of the people, the candidate of small government, the arrogant preacher, and the meek me-too-er. He backed off of using quasi-populist themes that had clearly boosted his standing when he plugged them hard. He blew the debates. He alienated liberals with a final TV ad that boasted of his role in welfare reform. He lost his home state of Tennessee to George W. Bush by 51 to 48 percent and President Clinton’s home state of Arkansas by 51 to 45 percent. He turned off young voters with the selection of Joe Lieberman as his running mate and their condescending attacks on popular entertainment, producing a huge drop-off in Democratic voting among those twenty-nine and younger, costing the ticket almost 3 million votes compared to 1996. Pat Buchanan’s gallbladder operation in late summer defanged his right-wing threat to Bush. Ten times as many Florida Democrats voted for Bush than swung to Nader. Senior citizens, the supposed core of Gore’s base in that crucial state, split their vote evenly between the two major candidates. And some of the reasons for Gore’s loss were ostensibly procedural. The television networks’ premature announcement of Bush’s “victory” and the vice president’s aborted concession speech on Election Night created a psychological dynamic that made it nearly impossible for Gore to push for a full recount in Florida.

Bush’s allies in Florida and on the Supreme Court also prevented a proper recount there, while tens of thousands of former felons living in the state— people who had paid their debt to society — were illegally denied their right to vote by Republican registrars. Outdated vote-counting technology produced disproportionate undercounts in districts with high minority populations. The “butterfly ballot,” designed and approved by Democratic election officials, confused older voters in Palm Beach County, costing Gore thousands of likely votes. And while the Republicans went all-out to defend their ill-gained Florida win, even sending young Hill staffers to verbally and physically harass local election officials, the Gore campaign told labor organizers, minority-rights activists, and other Democratic partisans to sheath their swords and avoid similar confrontations. Maintaining the appearance of political stability in America was, in the end, more important to Gore than fighting for the principle of “one-person, one-vote.” But in the days and weeks after Election Day, these points were rarely heard. Instead, only one message was voiced by politicos and editorialists alike: Ralph Nader spoiled Al Gore’s chances for victory...

Ironically, Reform Party candidate Pat Buchanan actually “cost” George Bush more states and more electoral votes than Nader did Gore, if one assumes for argument’s sake that every vote Buchanan and Nader got would have instead gone to the major-party candidate closest to them on the political spectrum. And Nader’s presence in the election arguably helped Gore in two significant ways. First, by impelling Gore to strengthen his own appeal to the lower half of the electorate with neopopulist rhetoric about taking on the drug companies, the oil companies, and HMOs, Nader indirectly shifted the tilt of the Democrat’s message in a way that clearly improved Gore’s polling. And second, by standing to Gore’s left, Nader made it extremely hard for the Republicans to paint Gore as “hopelessly liberal”— the tactic they had used with great success in their presidential victories in 1980, 1984, and 1988.

Some observers saw beyond the anti-Nader vitriol. “The passions aroused by the Nader campaign have much in common with those elicited by John McCain and Bill Bradley in their primaries,” wrote Robert Reich, former Clinton labor secretary, a few weeks after the vote. “We are witnessing the birth pangs of a reform movement in America intent on ending the corruption of our democratic system by money.” Reich urged that “this is the hour for reform, not recrimination.”....

It seemed as if the worst of all worlds had happened. Nader had failed to win the 5 percent the Greens needed to get federal funding for the 2004 presidential campaign and he was perceived, rightfully or wrongfully, as the number one reason Democrats lost the election.

··························································

"Serious, credible, platform-based"

- "A politics of values, independent, forward-looking vision"

“The goal of our founding platform was to have a Green Party policy foundation on which Green candidates could run ‘serious, credible, platform-based campaigns’, that is, to succeed in the goal of effective political campaigning taking the Green Party positions in the platform and turning them into reality.”

- -- Steven Schmidt

○