Hubble

Thanks Hubble for expanding our perspective

The Story of Hubble -- and Scientists Who Created and Saved It

What's Coming After Hubble? The James Webb

Next up, Say Hello to James Webb (To launch in 2018)

http://www.greenpolicy360.net/w/File:Webb_Telescope_construction_completed-Nov2016.jpg

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○

February 2017

NASA/JPL Reveal Largest Batch of Earth-Size, Habitable-Zone Planets Around Single Star

The fact that they transit their star also means that scientists will be able to do plenty of followup observations that will characterize the atmospheres of the worlds thanks to the light shining on them from the star.

All of the planets are far enough from their star that they could conceivably host liquid water on their surfaces, according to the researchers. Four of the worlds in particular are thought to be in the "habitable zone" of the star, which means they could be our best chances for life outside the solar system.

The Hubble Space Telescope characterized the atmospheres of TRAPPIST-1B and TRAPPIST-1C, finding that the two worlds probably aren't encircled by hydrogen and helium rich atmospheres, meaning their atmospheres could resemble our own.

Researchers will be able to get an even better look at these worlds in the future.

NASA's James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) — Hubble's telescope successor expected to launch in 2018 — should be able to peer deeply into the atmospheres of alien planets to try to see if they really could be like our own.

The JWST might be able to pick out oxygen, carbon dioxide, methane and other molecules in exoplanet atmospheres to find any biosignatures that might be present.

○

April 2015

- Hubble's 25th Anniversary

Turning Black-and-White Images Into Masterpieces (National Geographic)

○

by Anthony Doerr

The following article is courtesy of Orion Magazine - Subscribe to Orion

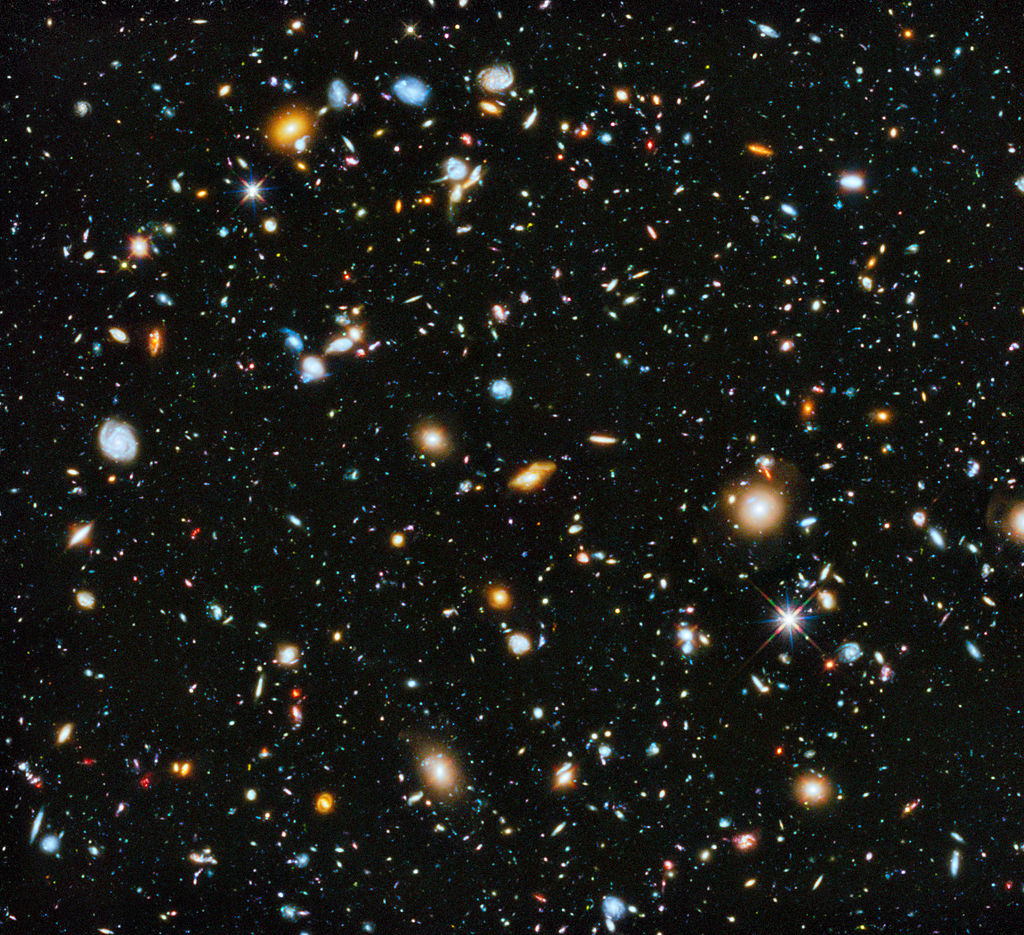

Hubble Ultra Deep Field

We call our galaxy the Milky Way. There are at least 100 billion stars in it and our sun is one of those. A hundred billion is a big number, and humans are not evolved to appreciate numbers like that, but here’s a try: If you had a bucket with a thousand marbles in it, you would need to procure 999,999 more of those buckets to get a billion marbles. Then you’d have to repeat the process a hundred times to get as many marbles as there are stars in our galaxy.

That’s a lot of marbles.

So. The Earth is massive enough to hold all of our cities and oceans and creatures in the sway of its gravity. And the sun is massive enough to hold the Earth in the sway of its gravity. But the sun itself is merely a mote in the sway of the gravity of the Milky Way, at the center of which is a vast, concentrated bar of stars, around which the sun swings (carrying along Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, etc.) every 230 million years or so. Our sun isn’t anywhere near the center; it’s way out on one of the galaxy’s minor arms. We live beyond the suburbs of the Milky Way. We live in Nowheresville.

But still, we are in the Milky Way. And that’s a big deal, right? The Milky Way is at least a major galaxy, right?

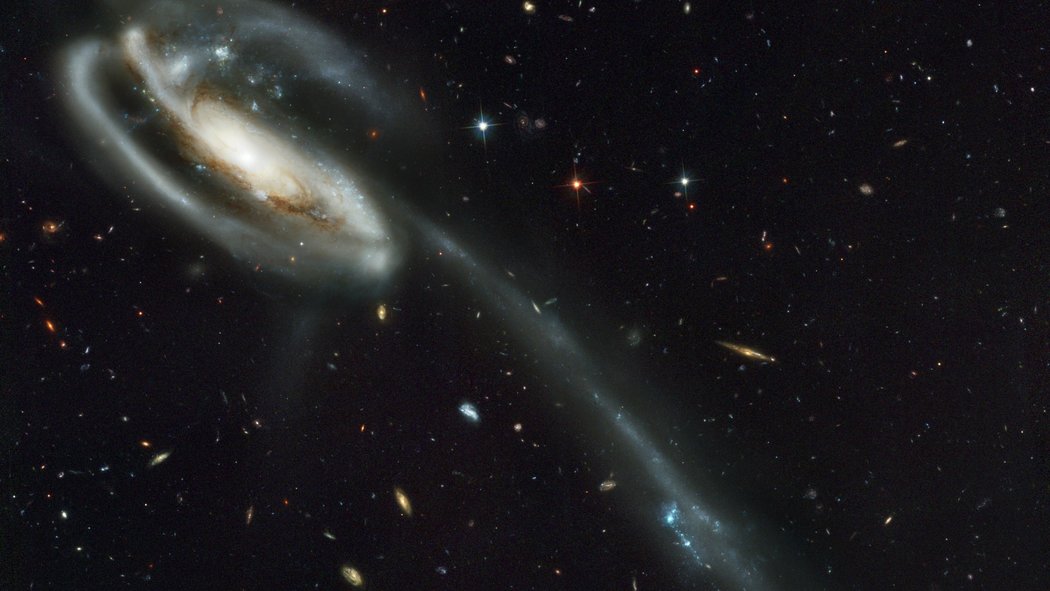

Not really. Spiral-shaped, toothpick-shaped, sombrero-shaped — in the visible universe, at any given moment, there are hundreds of thousands of millions of galaxies. Maybe as many as 125 billion. There very well may be more galaxies in the universe than there are stars in the Milky Way.

So. Let’s say there are 100 billion stars in our galaxy. And let’s say there are 100 billion galaxies in our universe. At any given moment, then, assuming ultra-massive and dwarf galaxies average each other out, there might be 10,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 stars in the universe. tThat’s 1.0 X 10 to the twenty-second power. That’s 10 sextillion.

Here’s a way of looking at it: there are enough stars in the universe that if everybody on Earth were charged with naming his or her share, we’d each get to name a trillion and a half of them.

Even that number is still impossibly hard to comprehend — if you named a star every time your heart beat for your whole life, you’d have to live about 375 lifetimes to name your share.

○

Last year, a handful of astronomers met in London to vote on the top ten images taken by the Hubble Telescope in its sixteen years in operation. They chose some beauties: the Cat’s Eye Nebula, the Sombrero Galaxy, the Hourglass Nebula. But conspicuously missing from their list was the Hubble Ultra Deep Field image. It is, I believe, the most incredible photograph ever taken.

In 2003, Hubble astronomers chose a random wedge of sky just below the constellation Orion and, during four hundred orbits of the Earth, over the course of several months, took a photograph with a million-second-long exposure. It was something like peering through an eight-foot soda straw with one big, superhuman eye at the same wedge of space for eleven straight nights.

What they found there was breathtaking: a shard of the early universe that contains a bewildering array of galaxies and pre-galactic lumps. Scrolling through it is eerily similar to peering at a drop of pond water through a microscope: one expects the galaxies to start squirming like paramecia. It bewilders and disorients; the dark patches swarm with questions. If you peered into just one of its black corners, took an Ultra Deep Field of the Ultra Deep Field, would you see as much all over again?

What the Ultra Deep Field image ultimately offers is a singular glimpse at ourselves. Like Copernicus’s On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres, it resets our understanding of who and what we are.

As of early April 2007, astronomers had found 204 planets outside our solar system. They seem to be everywhere we look. Chances are, many, many stars have planets or systems of planets swinging around them. What if most suns have solar systems? If our sun is one in 10 sextillion, could our Earth be one in 10 sextillion as well? Or the Earth might be one — just one, the only one, the one. Either way, the circumstances are mind-boggling.

The Hubble Ultra Deep Field is an infinitesimally slender core-sample drilled out of the universe. And yet inside it is enough vastness to do violence to a person’s common sense. How can the window of possibility be so unfathomably large?

Take yourself out to a field some evening after everyone else is asleep. Listen to the migrant birds whisking past in the dark; listen to the creaking and settling of the world. Think about the teeming, microscopic worlds beneath your shoes — the continents of soil, the galaxies of bacteria. Then lift your face up.

The night sky is the coolest Advent calendar imaginable: it is composed of an infinite number of doors. Open one and find ten thousand galaxies hiding behind it, streaming away at hundreds of miles per second. Open another, and another. You gaze up into history; you stare into the limits of your own understanding. The past flies toward you at the speed of light. Why are you here? Why are the stars there? Is it even remotely possible that our one, tiny, eggshell world is the only one encrusted with life?

The Hubble Ultra Deep Field image should be in every classroom in the world. It should be on the president’s desk. It should probably be in every church, too.

“To sense that behind anything that can be experienced,” Einstein once said, “there is a something that our mind cannot grasp and whose beauty and sublimity reaches us only indirectly and as a feeble reflection, this is religiousness.”

Whatever we believe in — God, children, nationhood — nothing can be more important than to take a moment every now and then and accept the invitation of the sky: to leave the confines of ourselves and fly off into the hugeness of the universe, to disappear into the inexplicable, the implacable, the reflection of that something our minds cannot grasp.

-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-

Anthony Doerr lives in Boise, Idaho. He is the recipient of the Rome Prize, the Discover Prize, and three O. Henry Awards. He is the author of both fiction (The Shell Collector: Stories) and nonfiction (Four Seasons in Rome: On Twins, Insomnia, and the Biggest Funeral in the History of the World). His fourth book, a collection of stories titled Memory Wall.

Orion Nebula