File:The little things that run the world.gif: Difference between revisions

Siterunner (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Siterunner (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

<small>(The Importance and Conservation of Invertebrates)</small> | <small>(The Importance and Conservation of Invertebrates)</small> | ||

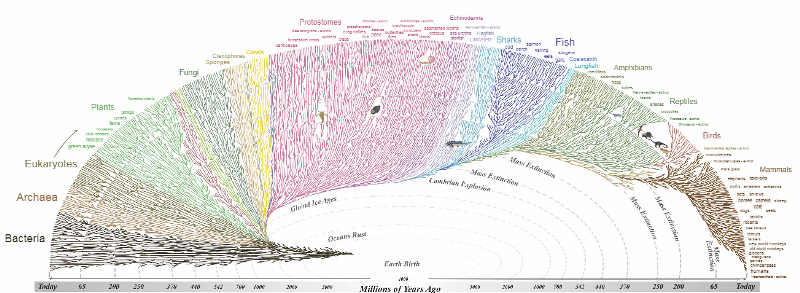

[[File:Tree of Life Explorer - Evogeneao.png | [[File:Tree of Life Explorer - Evogeneao.png]] | ||

::<small>'''[[Tree of Life]]'''</small> | ::<small>'''[[Tree of Life]]'''</small> | ||

Michael Malay, Nov. 2018 | |||

''(There was a time) when the American countryside was teeming with insect life, a time of incredible abundance for those “little things” that, in biologist’s E. O. Wilson’s phrase, [https://www.jstor.org/stable/2386020?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents “run the world.”] Today, the prospects for insect life are very different.'' | |||

''While rates of insect extinction are increasing there seems to be no corresponding shift in our attention to these species. Insects remain the victims of human ignorance and industrial pesticides – a doubly lethal combination...'' | |||

''One problem is how to encourage citizens to care about animals about which they know little. How does one begin to appreciate the loss of the endangered Darkling Beetle, the V Moth, or the Wart Biter cricket, especially when these animals are not part of our daily experience? Another problem is the difficulty of visualising these threats. Images of polar bears on melting ice have a visceral effect, but it is much harder to observe – and therefore to feel – the damage that is being wrought to insect life. So much destruction is happening at a scale which is beyond our capacity to see it.'' | |||

''One of the key tasks, therefore, is to find ways of portraying the ‘great thinning’ in ways that can’t be ignored, and it is here that artists, poets and environmental scholars have a role to play. By asking different questions from conservationists, and bringing new perspectives to bear on the issue, they may be able to illuminate the consequences of extinction in other ways. “The hardest thing of all to see is what is really there,” the writer J. A. Baker wrote in his classic book, The Peregrine. That statement is no less true today, but perhaps it is much more urgent.'' | |||

''In his book [http://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=9780674008182 Song of the Earth], the scholar Jonathan Bate argues that we can think of nature poems as ecosystems – as texts that imaginatively recreate the landscapes they describe. But what if we extended that thought a little further? What if we also thought of poems as vulnerable ecosystems, as living landscapes that continue to be affected by changes that are happening today?'' | |||

○ | |||

* https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0185809 | |||

''Global declines in insects have sparked wide interest among scientists, politicians, and the general public. Loss of insect diversity and abundance is expected to provoke cascading effects on food webs and to jeopardize ecosystem services. Our understanding of the extent and underlying causes of this decline is based on the abundance of single species or taxonomic groups only, rather than changes in insect biomass which is more relevant for ecological functioning. Here, we used a standardized protocol to measure total insect biomass using Malaise traps, deployed over 27 years in 63 nature protection areas in Germany (96 unique location-year combinations) to infer on the status and trend of local entomofauna. Our analysis estimates a seasonal decline of 76%, and mid-summer decline of 82% in flying insect biomass over the 27 years of study. We show that this decline is apparent regardless of habitat type, while changes in weather, land use, and habitat characteristics cannot explain this overall decline. This yet unrecognized loss of insect biomass must be taken into account in evaluating declines in abundance of species depending on insects as a food source, and ecosystem functioning in the European landscape.'' | |||

○ | ○ | ||

Latest revision as of 12:58, 30 December 2021

The Little Things that Run the World

(The Importance and Conservation of Invertebrates)

Michael Malay, Nov. 2018

(There was a time) when the American countryside was teeming with insect life, a time of incredible abundance for those “little things” that, in biologist’s E. O. Wilson’s phrase, “run the world.” Today, the prospects for insect life are very different.

While rates of insect extinction are increasing there seems to be no corresponding shift in our attention to these species. Insects remain the victims of human ignorance and industrial pesticides – a doubly lethal combination...

One problem is how to encourage citizens to care about animals about which they know little. How does one begin to appreciate the loss of the endangered Darkling Beetle, the V Moth, or the Wart Biter cricket, especially when these animals are not part of our daily experience? Another problem is the difficulty of visualising these threats. Images of polar bears on melting ice have a visceral effect, but it is much harder to observe – and therefore to feel – the damage that is being wrought to insect life. So much destruction is happening at a scale which is beyond our capacity to see it.

One of the key tasks, therefore, is to find ways of portraying the ‘great thinning’ in ways that can’t be ignored, and it is here that artists, poets and environmental scholars have a role to play. By asking different questions from conservationists, and bringing new perspectives to bear on the issue, they may be able to illuminate the consequences of extinction in other ways. “The hardest thing of all to see is what is really there,” the writer J. A. Baker wrote in his classic book, The Peregrine. That statement is no less true today, but perhaps it is much more urgent.

In his book Song of the Earth, the scholar Jonathan Bate argues that we can think of nature poems as ecosystems – as texts that imaginatively recreate the landscapes they describe. But what if we extended that thought a little further? What if we also thought of poems as vulnerable ecosystems, as living landscapes that continue to be affected by changes that are happening today?

○

Global declines in insects have sparked wide interest among scientists, politicians, and the general public. Loss of insect diversity and abundance is expected to provoke cascading effects on food webs and to jeopardize ecosystem services. Our understanding of the extent and underlying causes of this decline is based on the abundance of single species or taxonomic groups only, rather than changes in insect biomass which is more relevant for ecological functioning. Here, we used a standardized protocol to measure total insect biomass using Malaise traps, deployed over 27 years in 63 nature protection areas in Germany (96 unique location-year combinations) to infer on the status and trend of local entomofauna. Our analysis estimates a seasonal decline of 76%, and mid-summer decline of 82% in flying insect biomass over the 27 years of study. We show that this decline is apparent regardless of habitat type, while changes in weather, land use, and habitat characteristics cannot explain this overall decline. This yet unrecognized loss of insect biomass must be taken into account in evaluating declines in abundance of species depending on insects as a food source, and ecosystem functioning in the European landscape.

○

File history

Click on a date/time to view the file as it appeared at that time.

| Date/Time | Thumbnail | Dimensions | User | Comment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| current | 15:26, 3 November 2018 |  | 760 × 972 (55 KB) | Siterunner (talk | contribs) |

You cannot overwrite this file.

File usage

The following 4 pages use this file: